Was it me or my implant?

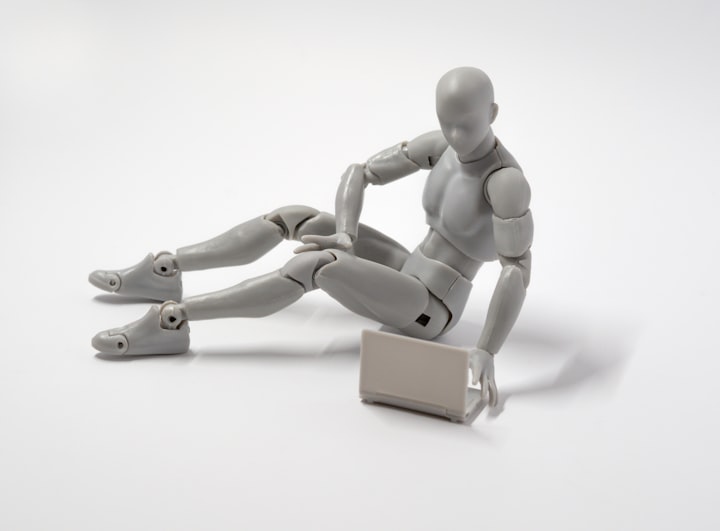

Elon Musk wants to create a new generation of brain implants with Neuralink. Already today, such devices help patients with certain diseases — but they also raise ethical concerns.

“It becomes a part of you”, is how patient 6 describes the device that changed her life after a 45-year history of severe epilepsy. Implanted brain electrodes send signals to a hand-held device as soon as signs of an impending epileptic seizure appear. A warning tone now reminds the patient to suppress the impending seizure with medication. “You grow into it slowly and get so used to it that at some point it becomes commonplace,” she tells neuroethics Frederic Gilbert from the Australian University of Tasmania, who works with brain-computer interfaces (BCI).

In 2019, Gilbert and his colleagues asked six BCI wearers from a first clinical study how the device affects them psychologically. Patient 6 had the most extreme experience: It was a kind of symbiosis, according to Gilbert. Ecologists understand the term to mean a close coexistence of individuals of two species for the benefit of both.

Brain-computer interfaces can be divided into those that “read” the brain, i.e. record brain activity and decode its meaning, and those that “write” into the brain to manipulate the activity of certain regions and thus influence their function. Scientists from the social media platform Facebook, for example, invented brain-reading techniques for headphones, which are designed to convert the brain activity of users into text.

AT A GLANCE

FREE WILL AND ALGORITHMS

- Techniques such as deep brain stimulation or brain-computer interfaces are becoming increasingly important and have already helped several patients.

- These systems directly intervene in the human thought organ. This raises the question as to the extent to which their use is ethically justifiable.

- In some systems, AI algorithms take decisions from the human brain. Thus the subjective authorship of the actions becomes questionable.

Neurotechnology companies such as Kernel in Los Angeles or the Neuralink company founded by Elon Musk in San Francisco are even speculating on bidirectional connections, in which the computer both reacts to human brain activity and feeds information into the neural circuit.

Neuroethics observe such developments very closely. This discipline, which has been growing for around 15 years, ensures that techniques that directly influence the brain remain ethically justifiable. “We don’t want to be the guardians of order in the neurosciences or dictate what applications neurotechnology will produce,” stresses neuroethics Marcello Inca from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. Rather, he and his colleagues are calling for ethical considerations to be taken into account right from the initial drafts and various stages of development regarding these technologies. After all, this would enable potential risks to be identified and contained at an early stage — whether for the individual or society as a whole.

It’s already becoming apparent that the fusion of digital technologies with the human brain sometimes has far-reaching consequences for a person. This may even affect their free will, i.e. their ability to behave according to their own decisions. Even though the focus of neuroethics is on medical practice, they are also involved in the debates on the development of commercial neurotechnologies.

In the late 1980s, French scientists inserted electrodes into the brains of Parkinson’s patients in whom the disease was already well advanced. Electrical currents in the areas of the brain presumably responsible for the tremor were intended to suppress neuronal activity there. This deep brain stimulation helped many of those affected enormously: violent and exhausting tremors subsided immediately as soon as the electrodes were switched on.

Increased sex drive after brain stimulation

In 1997, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved deep brain stimulation for the treatment of Parkinson’s symptoms. Since then, the method has been tested for various other diseases: it is now approved for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorders and epilepsy and is being tested for mental disorders such as depression or anorexia.

Since the method directly targets the organ from which our sense of identity originates, it is fraught with many fears. One of these concerns our autonomy, says Hannah Maslen, neuroethics from the University of Oxford. Some Parkinson’s patients, for example, have experienced increased sex drive after deep brain stimulation or have had less control over their impulses. A pain patient, on the other hand, became profoundly apathetic. “The method is very useful,” says Gilbert, “to the point where it distorts the patient’s self-perception.

Other people whose brains had been stimulated because of depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder even felt that they were no longer free to make decisions about their actions. “You wonder how much of yourself is left,” says one person affected. “What part of my thoughts comes from me? And how would I act if I didn’t have the stimulation system? You feel somehow artificial.”

It is only gradually that neuroethics is beginning to recognize the true scope of the therapy. “Some side effects such as personality changes are more serious than others,” says Maslen. What is important is whether the patient consciously notices how he or she changes after the stimulation. Gilbert describes a patient who became addicted to gambling and gambled away his family’s savings. It was only when the stimulation was switched off that he could understand how problematic his behavior was.

Such cases raise serious fears that the technique could impair his judgment. Should a family member or a doctor be able to veto a stimulation patient’s request for further treatment? If so, this would imply that the technique limits their ability to make their own decisions. This is because thoughts that only occur as long as an electric current affects brain activity may not originate from one’s self.

Such dilemmas become particularly difficult if therapy is explicitly aimed at behavioral changes, such as in anorexia. “If a patient says before deep brain stimulation: ‘I am someone who cares more about being slim than anything else’, and you then stimulate his or her brain so that his or her behavior or attitude changes,” explains Maslen, “then we need to know whether this change of heart is wanted by the patient.

She and other scientists want to draw up more precise consent forms for the stimulation treatment. It should include a detailed consultation during which all possible consequences and side effects will be discussed in detail.

It’s impressive to watch a paraplegic man carrying a glass of water to his mouth with a robotic arm that he controls via a readout BCI. The rapidly developing technology is based on electrode arrays that are implanted at or in a region of the brain responsible for planning and executing movements. For example, while the subject imagines moving his hand, his brain activity is recorded to generate commands for the robotic arm.

If these neural signals could be distinguished from the background noise and assigned to the will of the person, the ethical problems would be manageable. But this is not the case. The neuronal correlates of mental processes are poorly understood so that the brain signals must be processed by artificial intelligence (AI).

According to the neurologist Philipp Kellmeyer of the University of Freiburg, the use of AI and machine learning algorithms to decipher neural activity has turned the entire field upside down. He refers to a study published in 2019, in which such software interpreted the brain activity of mute epilepsy patients to generate synthetic speech sounds. “Two or three years ago,” he says, “we would have thought that this was either impossible or would take another 20 years.

Black box with access to the brain

However, AI tools also raise ethical questions with which regulatory authorities, for example, have little experience. Machine learning software is based on data analysis that is difficult to understand. As a result, an unknown and hardly comprehensible process stands between the thoughts of a person and the technology that acts on their behalf.

Prostheses work better when BCI devices try to predict what the patient will do next. The advantages of this are obvious: For seemingly simple but in reality highly complex actions, such as reaching for a coffee cup, the brain unconsciously makes many calculations. Prostheses that use sensors to autonomously perform related movements make it much easier for the user to cope with them. This also means, however, that much of what a robotic arm does is not really from the patient.

Predictive properties of this kind pose further problems that are familiar to every cell phone user. The automatic text recognition of cell phones is often helpful and saves time — but anyone who has inadvertently sent a message with the wrong auto-correction knows that sometimes something can go wrong.

Such algorithms learn from previous data and take decisions from the user based on his past actions. However, if an algorithm constantly suggests the next word or action and the human merely accepts the suggestion, the authorship of the message or action becomes questionable. “At some point, this strange state of a common or hybrid will emerges,” explains Kellmeyer. One part of the decision comes from the user and another from the machine.

“This creates a responsibility gap.”

Hannah Maslen is dealing with this in the EU project BrainCom, which develops speech generators. The systems should make audible what a person wants to say. To prevent errors, the user can be allowed to release every single word. But constant feedback of speech fragments would probably make the whole thing a tedious business.

Such reassurances would be particularly important, however, if the devices have difficulty distinguishing between the neural activity for speaking and that for thinking. Our society rightly demands fundamental boundaries between private thoughts and external behavior.

The symptoms of many brain diseases appear unpredictably. Therefore, methods for brain monitoring are increasingly used. Such recording electrodes — as inpatient 6 — track brain activity to identify when symptoms occur or are imminent. However, instead of simply giving the user a hint, some autonomously send a command to a stimulation electrode. This electrode suppresses the relevant brain activity as soon as an epileptic seizure or tremor in Parkinson’s patients becomes apparent. The FDA approved such a closed-loop system for the treatment of epilepsy as early as 2013; similar systems for Parkinson’s therapy are undergoing clinical testing.

Suddenly no longer able to mourn

The problem here is: Does a person still act in a self-determined way after the introduction of a decision-making device in his brain — possibly linked to an autonomously acting AI software? In the case of devices that control blood sugar levels and insulin administration for diabetics, this automatic decision-making process is undisputed. However, the situation is different for interventions in the brain. For example, a person who uses a closed-loop system to treat an affective disorder might become unable to feel any negative emotion, even if that would be perfectly normal, such as at a funeral. “If a device constantly interferes with your thinking or decision making,” says Gilbert, “it can restrict you as a freely acting person.

The epilepsy BCI used by the users interviewed by Gilbert left them in control by warning them of impending seizures. This left them with the decision of whether or not to take medication. Nevertheless, for five of the six patients, the device became the main decision-maker in their lives. Only one of the six patients usually ignored it. Patient 6 fully accepted the device as an integral part of her new self. Three users relied on it willingly without feeling that their self-image had changed fundamentally. Another subject, however, fell into depression and reported that the BCI made him feel that he was no longer in control.

“The decision is ultimately up to you,” says Gilbert. “But the moment you realize that the device is more effective than you are in certain situations, you no longer pay attention to your assessment. You rely on the device.”

The goal of neuroethics — maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks — has long been embedded in medical practice. The development of commercial techniques for consumers, on the other hand, is mostly hidden and hardly subject to any control. Technology companies are already researching the feasibility of BCI devices for the mass market. Marcello Inca sees an important moment here: “When a method is still in its early stages, the results are very difficult to predict. However, when it is mature in terms of market size or opening, it may already be too well established to intervene”. In his opinion, we now know enough to act competently before the widespread use of neurotechnologies becomes a reality.

One problem, according to Ienca, is privacy. “Information from the brain is probably the most intimate and private of all data,” he emphasizes. It could be stolen by hackers or used inappropriately by companies to which users have given access. Ienca stresses that because of the concerns of neuroethics, manufacturers should have looked at the security of their devices to better protect their users’ data. They could no longer demand access to social media profiles and other sources of personal information as a condition of device use. However, consumer privacy remains a challenge due to the ever faster-evolving neurotechnologies.

Privacy and free will are among the main topics in the recommendations issued by various working groups and large-scale neuro-research projects. Nevertheless, Philipp Kellmeyer believes there is still a lot to be done. “The basic assumptions of conventional ethics based on autonomy, justice, and related concepts will not suffice,” he says. “We also need ethics and philosophy of human-technical interactions.” Many neuroethics believe that a revision of basic human rights is necessary because of the possibility of directly manipulating the brain.

Hannah Maslen is advising the European Commission on directives on over-the-counter, non-invasive devices that manipulate the brain. At present, only lax safety regulations apply to this. The devices may look harmless, but they conduct electrical currents through the top of the skull to manipulate brain activity. According to Maslen, the stimulation can cause headaches and visual disturbances and in some cases even lead to burns.

She also cites clinical studies that show that techniques of non-invasive brain stimulation enhance certain mental abilities, but only at the expense of other cognitive performances.

Frederic Gilbert’s research on the psychological effects of BCI devices illustrates what is at stake when companies develop methods that can fundamentally change people’s lives. Since the company that implanted BCI into the brain of patient 6 went bankrupt, it had to be removed. “She refused and delayed as long as possible,” says Gilbert. Crying, she told Gilbert after the removal of the device, “I lost myself.”

About the Creator

AddictiveWritings

I’m a young creative writer and artist from Germany who has a fable for anything strange or odd.^^

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.