The Soil That Remembered: Unearthing Britain’s Microbial Time Capsules

In the forgotten burial grounds of Iron Age Britain, scientists discover microorganisms that preserve memory—reshaping how we understand history, disease, and consciousness

1. Beneath the Moors

In the windswept stillness of Yorkshire’s North York Moors, archaeologist Dr. Isla Renfield thought she’d found another mundane Iron Age burial mound. The peat had preserved bones, tools, even the remnants of woven linen. All expected. All familiar.

But when forensic microbiologist Dr. Riyad Malik joined the dig in 2026, everything changed.

Using a new genomic soil scanner from the University of Edinburgh, Malik detected an anomaly in the soil samples surrounding the remains—a concentration of microbes with DNA sequences that matched no known database.

And stranger still, these microbes formed patterns—complex, non-random, almost linguistic sequences.

2. The Language of Dirt

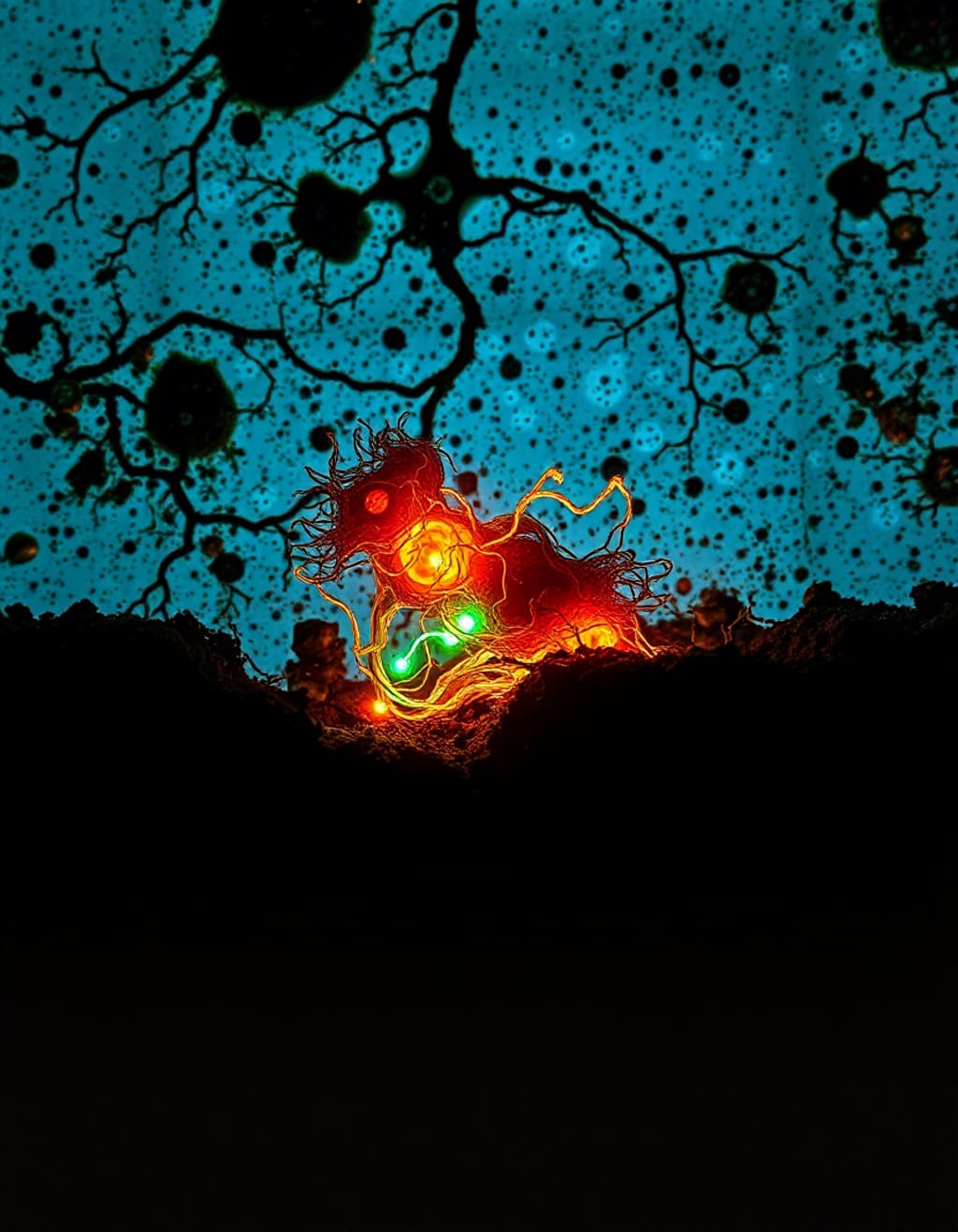

Microbiomes are everywhere—in soil, water, air, even our skin. But these soil-dwelling microbes were encoding sequences that mimicked semantic structures—as if the soil had recorded information, and preserved it.

These weren’t pathogens. They were storytellers.

The scientists named the phenomenon “Bioencoding.” Simply put: the microbes had absorbed environmental signals—chemical, biological, and thermal—and structured them into retrievable data.

Forensic linguists confirmed that when sequenced and translated, the microbial DNA patterns showed fragments of Iron Age Brythonic words—the ancient Celtic language spoken across pre-Roman Britain.

It was as if the microbes had listened for 2,000 years—and remembered.

3. Microbial Memory

So how could this be?

It turns out that certain extremophilic bacteria—those that live in oxygen-poor, acidic soil—undergo horizontal gene transfer, absorbing foreign DNA and adapting quickly to environmental pressures.

But in this case, they didn’t just adapt.

They preserved.

The microbes had locked fragments of human RNA and protein structures from nearby skeletal remains, weather conditions, organic plant matter, and even decaying textile fibres—and had encoded them as a collective, like a biological hard drive.

The soil was a memory field.

And Britain, covered in thousands of such burial sites, suddenly became the largest natural historical database on Earth.

4. A Message from Elidyr

In one burial mound, scientists discovered a particularly dense concentration of bioencoded microbes surrounding the skull of an adult male.

After decoding weeks of DNA sequences, researchers found one repeated set of translated phrases:

“Elidyr son of Bran. Fire of the northern gate. Taken in the night of frost. We walked alone. We remembered.”

This was not simply language. It was experience—the memory of trauma, encoded by proximity to death.

The microbes had essentially bio-recorded emotional and environmental cues—through stress hormones, body decay heat, and chemical residues.

Historians now debated: were these bacteria observing, or were they transcribing history in real-time?

5. The Path to Bio-History

By 2028, the University of Cambridge had developed Soil Memory Readers (SMRs)—machines that could rapidly sequence microbial patterns and reconstruct historical environmental conditions, language traces, and even dietary data.

They began testing soil from Stonehenge, Hadrian’s Wall, and the Sutton Hoo ship burial.

Each site revealed a microbial narrative—some confirming what we already knew, others rewriting timelines entirely.

One burial site near Cornwall showed microbial signatures indicating early trans-Atlantic contact, centuries before recorded Viking voyages. Another near Norwich suggested plague outbreaks a century earlier than previously believed.

It was the beginning of biohistorical archaeology—and Britain was leading it.

6. Consciousness or Contamination?

The implications were huge—and controversial.

If soil could preserve emotion-laden signals, could we one day read memories from ancient trauma sites?

Could we understand how people felt, not just what they built?

Some neuroscientists warned against romanticising the data. Dr. Malik, however, pushed forward. In 2029, his team demonstrated that certain peptides preserved in soil around burial remains carried emotion-related neurochemical traces—dopamine breakdowns, cortisol residues, adrenaline.

The bacteria weren’t sentient, but their environment was soaked in chemistry tied to human experience.

The soil had recorded not just what happened, but what it meant.

7. The Curse of Memory

Trouble soon followed.

In 2030, a private research company attempted to “read” a microbial memory from a battlefield near Stirling, where thousands had died in a medieval clash. They claimed their SMR found signals of terror so intense, it corrupted the decoding software.

Their servers failed. A technician had a seizure. The story went viral.

Though later debunked, it triggered a fierce debate: were there dangers in resurrecting emotional history?

The British Parliament passed the Historical Bioethics Act, placing restrictions on sequencing microbial data from human burial sites without consent or oversight.

Even memories, it seemed, needed legal protection.

8. Healing from the Soil

But the microbes offered more than history.

In 2031, Dr. Malik’s team discovered that certain proteins preserved in the soil showed natural antibiotic resistance profiles—essentially ancient blueprints for fighting infection.

Bacteria that had survived plagues, frostbite, battlefield injuries, and fungal decay offered genetic tools to fight modern diseases.

One such protein, derived from Elidyr’s mound, became the basis for a new class of neuroprotective drugs, now used in early-stage dementia treatment.

History wasn’t just informative. It was healing.

9. The British Soil Genome Project

Soon, a national effort began: to map and preserve soil microbiomes from every historical site in Britain.

It was called the British Soil Genome Project, led by scientists, historians, and AI linguists. Their goal: to create a layered, searchable database of every bioencoded soil memory—accessible to educators, researchers, and the public.

Using augmented reality, schoolchildren could visit Roman forts and see microbial history overlays, showing reconstructed scenes based on environmental data.

For the first time, history was alive—not in books, but in the ground beneath their feet.

10. What the Earth Knows

In her 2032 address to the Royal Society, Dr. Isla Renfield said:

“We have mistaken the past as dead. But our soil holds the breath, heat, sweat, and sorrow of every person who came before us. We walk on stories. We build on memories. The Earth knows—and now, it speaks.”

Across Britain, scientists continue to refine how microbial memory might help track migrations, climate shifts, disease evolution, and even lost dialects.

Some now propose that similar microbial memory may exist beneath the oceans, in permafrost, or on Mars.

The Earth, once seen as passive terrain, is now seen as a living historian.

And British soil—the dirt beneath moors and ruins—may be the most honest storyteller we’ve ever known.

About the Creator

rayyan

🌟 Love stories that stir the soul? ✨

Subscribe now for exclusive tales, early access, and hidden gems delivered straight to your inbox! 💌

Join the journey—one click, endless imagination. 🚀📚 #SubscribeNow

Comments (1)

This is fascinating! The idea of microbes encoding ancient language is mind-blowing. I wonder how widespread this bioencoding could be. Have we found other sites with similar microbial stories waiting to be decoded? It makes you think about what else the soil might be holding onto.