Researchers use light and crystals to create new materials on demand.

This recent advancement makes use of a phenomena known as plasmonic heating, which permits more accurate crystal formation.

One day, it may be possible to "draw" rather than "grow" crystals for use in a wide range of applications, including lasers, LEDs, and the semiconductors used in sensors in astronomical instruments, which would result in improved performance and reduced prices.

A group from Michigan State University, led by Elad Harel, has heated a gold nanoparticle with a laser, causing crystal formation in a lead halide perovskite solution. So, theoretically, it is conceivable to precisely 'draw' the crystals where they need to be in an electronic system by manipulating the gold nanoparticle, once more with the use of lasers.

Traditional methods for creating crystals for electronics include planting a crystal "seed" and then watching it grow, or vapour diffusion, in which the crystal precipitates out of a solution. These techniques, however, are imprecise and result in crystals that grow very randomly and aren't always in the proper place, shape, or size.

"In a device, one may need a very small quantity of crystalline material placed at very specific locations," Harel stated to Space.com.

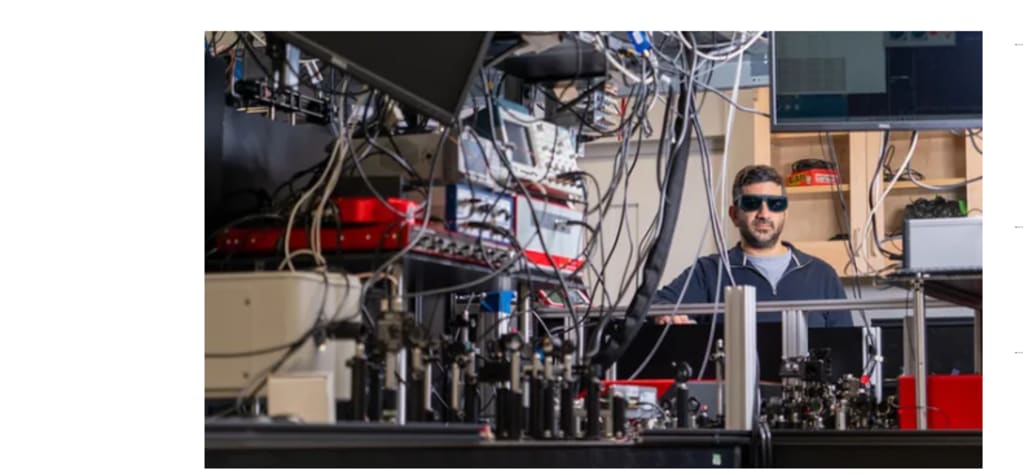

By employing a process called "plasmonic heating," Harel's novel method restores some degree of control over crystal formation. In lab tests, Harel's group aimed a 660 nm laser at a gold nanoparticle in a reaction chamber that contained the lead halide perovskite precursor solution over a borosilicate glass substrate that the crystal would be "drawn" onto.

The gold nanoparticle is minuscule, measuring less than a thousandth of a human hair's width. The entire process must therefore be incredibly accurate and observable in real time through the use of high-speed microscopes with frame rates of sub-millisecond intervals.

"The reason we use gold nanoparticles is because they act as small heaters," Harel stated. "When a laser irradiates the particle at the right frequency, it causes the electrons in the gold to oscillate, which generates heat." Plasmonic heating is what causes the precursor solution to crystallise in the precise places that Harel's group wants it to.

Although they perform well in solar cells and LEDs, lead halide perovskite crystals are not the only kind of crystal utilised in electronics. For instance, arsenic-doped silicon crystals are used in the semiconductors of the James Webb Space Telescope's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). Harel thinks that this plasmonic heating technique can be applied to other similar crystals, but it works for lead halide perovskites specifically because they have some very peculiar features.

"What's special about these perovskites is that as the temperature increases the solubility decreases, which induces crystallisation," he stated. "Most materials do not exhibit this retrograde solubility property; typically as the temperature increases, the solubility increases."

But the jiggling, stimulated electrons might hold the key to a solution. According to Harel, the electrons might theoretically directly contribute to the chemistry of crystal formation in addition to generating heat, hence promoting crystal formation. "We do need to do more work to generalise this concept to other materials, but we believe it will work," he stated.

The benefits of more accurate, quicker, and less expensive crystal formation are obvious. Touchscreens, smoke detectors, solar panels, medical imaging equipment, and the majority of optoelectronics and photodetectors in general all employ crystals.

"This is a very simple method using low-cost lasers," Harel stated. "It also saves enormously on the cost of fabrication since the crystal could be placed exactly where and when it is needed."

Because of the significance of crystals for astronomical sensing, the process of drawing them may even lead to the future deployment of less expensive devices on space missions.

The next stage is to try to "draw" more complex crystal patterns using several lasers at different wavelengths. After that, they will be tested in actual devices to see if they actually provide a higher quality of performance at a lower cost. "This is something we're working on right now," Harel replied.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.