Eliana moved carefully through the narrow streets of San Francisco. This was the part of the city where, at the oldest layer, adobe buildings began to give way to wooden structures. Some were Japanese, others Russian, and still others fantastically carved with images that told the sacred stories of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tshimshian clans which had built them. Surprisingly many remained, but they now filled in the crevices between the grey factories and the even greyer housing projects which the state had built to house those who worked there. Even here, so far from Tenochtitlan, the hand of the tlaoni was omnipresent, working ever since the victory of Raza Cosmica fifty years ago in 1821 to match the strength of the United States and now the Confederacy.

The revolution had never been what they had hoped it would be, but then revolutions never were. The Spanish were gone, to be sure, and the Church had been forced to declare its autonomy from the Vatican, which meant, in reality, simply its dependence on the tlaoni, who was gradually using it to create a sort of syncretic state religion. And there had been land reform, at least in the heart of Mexico. But taxes were heavy and every penny was going into creating an industrial base which would allow the tlaoni to ward off the expected onslaught from the East and, in the long run, liberate the lands of the Missisippians, the Iroquois, and the Algonquin.

Eliana had trained at the very best of the Yeshivas and calcemacs in Tenochtitlan and, despite being a Jew (or perhaps because of it) had been appointed to the political service, which combined the functions of a diplomatic corps, an intelligence service, and a political commissariat, ensuring that local authorities followed the political line of the tlaoni. It was a testimony to the legacy of her grandparents, who had swung Tenochtitlan’s large crypto-Jewish community behind the revolution, and then helped to steer it in a socialist direction, that she had been appointed at all. While her marks had always been high, she was known as something of a dissident with ties to the marginally tolerated Tikkun Olam group, and was strong willed or, as her “superiors” put it, insubordinate, and had spent much of her time at the calcemac subject to one or another form of discipline. That was probably why, in spite of her considerable linguistic skills, which included English, Mandarin, Japanese, Yiddish, and Russian as well as Nahuatl and Ladino she had been given this frontier posting rather than being sent to Washington or Montgomery, London or Beijing or the Pale as one would expect for a scion of the revolutionary aristocracy.

And now she found herself in something of a dilemma. Its many failings notwithstanding, as a Jew she was loyal to the Revolution and its Party, which in turn for the critical support offered by people like her grandparents, had ended the Inquisition and guaranteed not just religious freedom, but certain special privileges to the Jewish community. And she remained hopeful that Mexico would return to the socialist road. But what she had seen here in San Francisco had shaken her to the core. The city, which had one of the best harbors in the world, and which had, before the war, been an emerging port for the trade with China and the Indies, was now simply a lure for immigrants who were shipped off to the mines or put to work in the factories, little better than slaves, to be “expended” —as the party’s internal strategic documents admitted— in the cause of primitive socialist accumulation. And her job, as the most junior attache in the city’s political residency, was to gather intelligence on their feeble attempts at organization, and identify leaders to be “selected” for “re-education.” She was fortunate that in a bad posting like this the “resident” was drunken and incompetent and spent most of his sober time tending his “investments” in the gold rush areas to the East.

It did not take long for one of her counterparts from the opposition to spot her. She had been discussing the party’s —nonexistent— plan for improving conditions in the shipyards and housing blocks with a group of workers who had been staging work stoppages. Her lack of conviction must have been obvious. When she retired to the toilets during a break one of the young Chinese women in the group followed her and, as she was fumbling for some paper to cleanse herself, handed her a sheet of what looked like newsprint and then disappeared. As Eliana sat relieving herself she looked at the sheet and noticed the name of a tea house, the Tian Tao, circled in red. There was also a series of numbers circled in the same color. It took her a while to get them in a meaningful order: 1878 10 15 1730. It was a date and time. Eliana committed the address and numbers to memory, then used the paper to clean herself and returned to the meeting. When she saw the young Chinese woman she smiled gently and the woman smiled back.

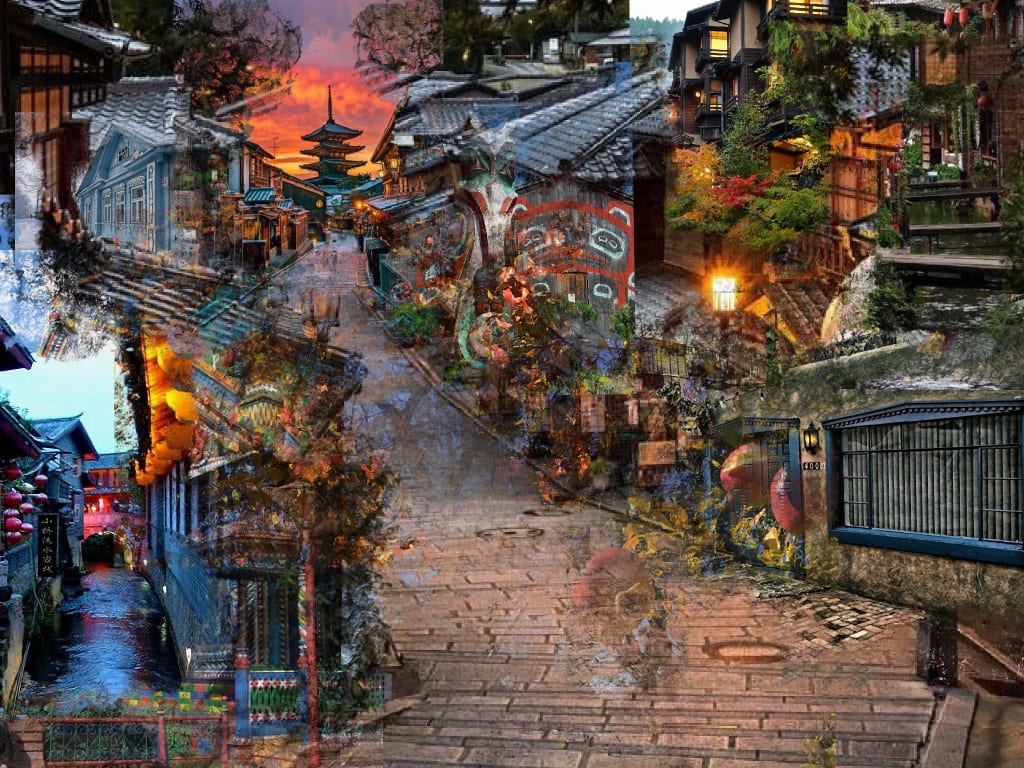

That had been three days ago. Now Eliana was navigating the narrow passages of the Chinese quarter to find the Tian Tao teahouse. It was the coldest day yet of an autumn which seemed to confirm that the climate itself was changing and, on the northwest coast of Azatlan, at least, getting colder. The air was crisp and the leaves of the many planted Japanese Maples red, orange and gold against the indigo sky, looking incongruous but strangely beautiful next to the date palms and Windmill Palms and the blood oranges planted in the closed gardens and peeking out above the wooden fences and adobe walls. That they had survived the tlaoni’s indigenization campaigns, which aimed to remove all foreign plants from Azatlan, marked this as a marginal neighborhood. To the west the sky was a brilliant orange as the day faded and everywhere gas lamps were being lit as night descended.

Finally, Eliana came to the alley she had been seeking and turned left, moving sharply downhill. She was more than a little nervous, as many of these alleys were cul-de-sacs and robberies and assaults were not uncommon. About a hundred meters down, however, the alley opened up into a tiny courtyard lit by gas lamps. There was a small shrine to Guan Yin surrounded by a cluster of fruit trees —pomegranates and persimmons all bearing fruit in this season, as well as an herb garden and clusters of Japanese Maples and date palms. On the far side of the courtyard there were several tables set out, empty in the chilly autumn, next to an entryway marked simply Tian Tao Cha.

Eliana entered cautiously, but the interior of the tea house was warm and welcoming, lit by candles and a small fire. She scanned the room searching for the young Chinese woman, whose name she did not yet even know, and seeing that she had not yet arrived, found a seat in the back corner of the establishment, being careful to catch the server’s eye as she sat down. When the server came she ordered a Puerh tea and a sesame pancake. Then she waited.

Like most political officers, she carried with her a small black notebook in which she kept a record of her contacts, notes on individual meetings, and outlines for reports to her superiors. Eliana, who was an accomplished artist, also kept sketches. But things had been busy and her mood not the best, so she had been rather neglecting her record keeping. This seemed like a good time to remedy that failure.

But before she could begin this process the server arrived with her tea and flatbread, so she set down her work and took a sip of tea. The server had also brought a small dish of water spinach with fermented tofu and another of lamb with chiles and cumin, a dish from the far west of China which had become a fast favorite in Chinese establishments serving the city’s Mexica elite.

Eliana looked up in surprise.

—They are on the house, the server said. Let me know if you need anything else.

Eliana was going to ask if the server had seen anyone meeting the description of her contact, but she had already disappeared. Realizing that she was hungrier than she had realized, she began to eat.

It was a few minutes before she returned to her work. When she did, turning to what should have been the first blank page of her notebook, marked by a scrap of newspaper, she found a rather extensive text in a script she did not recognize .

How, she wondered, had this gotten there? She slept with the notebook, took it to the toilet with her, and kept it wrapped up in her dress when she bathed.

She could not even begin to figure out what the text meant, though her linguistic and cryptographic skills were sufficient that she would likely be able to decipher it in time. And she had no idea how the writing had gotten there. But under the circumstances, it was clear who had done it. But such a strange way to choose to communicate …

Eliana fingered the page carefully. There was something behind it. She turned over the leaf and found, sitting there, a $1000 US Treasury note —one of the interest bearing notes issued by the Lincoln government to cover the expenses of a Civil War that after 17 years was going very badly. Turning the page she found an additional note in the same amount, and then another —20 in all.

Someone clearly wanted something from her. The question was who and for what. Eliana indulged for a moment the fantasy that the Chinese workers at the shipyard had found a financial sponsor and were asking for covert assistance in organizing. But why this strange message written in what was almost certainly an artificial and probably medieval script? And why United States banknotes? Lincoln was an old ally of the Mexica, but everyone knew that the war was going badly for him in part because the tlaoni had long been playing the United States off against the Confederacy, draining Union resources and advancing what everyone knew were continental ambitions. This would take some investigation. And clearly the young Chinese woman was not going to just show up and explain everything.

Eliana signaled the server, who brought her the check, which she paid immediately. Then she left the tea house and crossed the courtyard. There, looking straight at her, and clearly waiting for her were two women: one, a tall, thin and African in cornrows, the other obviously a Yankee, with pale skin and a mousy appearance, light brown hair, and blue eyes.

Perhaps, Eliana thought, I am going to find out what this is all about sooner rather than later.

About the Creator

Anthony Mansueto

I am social theorist, philosopher, political theologian and institutional organizer. I also write fiction which crosses the boundaries between magical realism and science fiction, mysteries and stories of espionage.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.