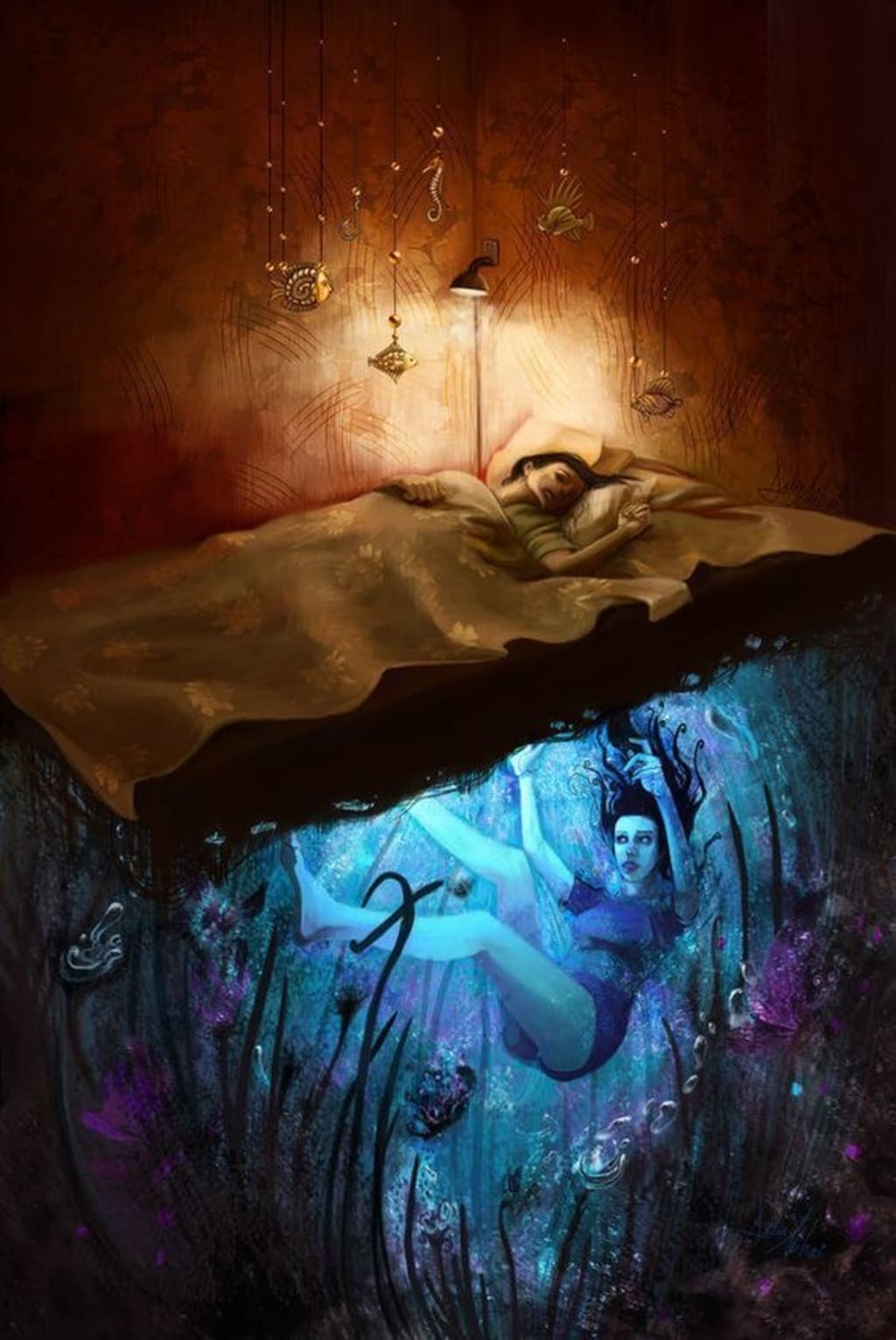

Dreams have fascinated humans for millennia, from ancient civilizations interpreting dreams as messages from gods to modern-day scientists attempting to decode the mysteries of the subconscious. We all experience dreams during sleep, but how and why do we dream? What happens in our brains that causes these vivid, sometimes strange, and often surreal experiences? Understanding the science behind dreaming requires diving into the stages of sleep, brain activity, and the theories that attempt to explain why we dream at all.

The Stages of Sleep and Dreaming

To understand how we dream, we must first understand sleep itself. Sleep occurs in cycles, typically lasting 90 minutes, and consists of several stages. These stages are categorized into two broad types: Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) Sleep and Rapid Eye Movement (REM) Sleep.

1. NREM Sleep:

• NREM sleep includes three stages: N1 (light sleep), N2 (deeper sleep), and N3 (slow-wave or deep sleep).

• Most physical rest and restoration occur during NREM sleep, including the repair of tissues, muscle growth, and immune system strengthening.

• Dreams can occur during NREM sleep, though they tend to be less vivid, less detailed, and more fragmented compared to those in REM sleep.

2. REM Sleep:

• REM sleep, which stands for Rapid Eye Movement, is where the most vivid dreams occur.

• During REM sleep, the brain is highly active, almost as active as when we are awake, with heightened brain wave activity, particularly in areas responsible for memory, emotions, and visual processing.

• The body experiences muscle atonia, meaning the muscles are temporarily paralyzed to prevent us from physically acting out our dreams.

Dreaming predominantly occurs during REM sleep, and these dreams are often more intense, imaginative, and emotionally charged. This is the stage of sleep that accounts for most of our conscious experiences of “dreaming.”

What Happens in the Brain During Dreaming?

While we sleep, the brain undergoes significant activity, even though our bodies are at rest. Brain scans during sleep have shown that certain regions of the brain are more active during REM sleep, which is when most vivid dreaming occurs:

• The Limbic System: This system, particularly the amygdala, plays a crucial role in emotions. It’s active during REM sleep, which may explain why many dreams are emotionally intense or anxiety-driven.

• The Prefrontal Cortex: This area of the brain is involved in logical thinking and decision-making. During REM sleep, the prefrontal cortex is less active, which could explain why dreams are often illogical or nonsensical. Without the rational brain “editing” the dream, our unconscious mind has the freedom to explore bizarre and fantastical scenarios.

• The Visual Cortex: This area processes images and visual stimuli. It is particularly active during REM sleep, which may be why many dreams are rich in visual detail and imagery.

• The Hippocampus: This part of the brain is responsible for memory consolidation. It’s believed that dreams help the brain process emotions and memories, which may explain why we often dream about recent experiences or unresolved issues.

Theories of Why We Dream

Dreams have been the subject of speculation and research for centuries. While science has not yet fully explained why we dream, several prominent theories attempt to shed light on this phenomenon.

1. The Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis

This theory, proposed by researchers Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley in 1977, suggests that dreams are a byproduct of the brain’s attempt to make sense of random neural activity that occurs during REM sleep. According to this hypothesis, the brain is essentially “randomly” activated during sleep, and our mind creates stories—dreams—to interpret this activity, trying to impose meaning on the randomness.

2. The Information-Processing Theory

This theory suggests that dreams serve a more functional purpose, helping us process and organize information. As we sleep, our brains consolidate memories, integrating new information with pre-existing knowledge. In this view, dreams are a way for the brain to sort through daily experiences, emotions, and memories, working through problems or unresolved emotions.

3. The Evolutionary Theory

The evolutionary theory of dreaming posits that dreams may have served an adaptive function in human evolution. According to this hypothesis, dreams may have been a rehearsal mechanism, allowing humans to practice and problem-solve in a safe environment (i.e., during sleep) without real-world consequences. For example, dreams involving escape or survival scenarios might have allowed early humans to practice responding to danger or threat.

4. The Psychoanalytic Theory

Pioneered by Sigmund Freud, the psychoanalytic theory suggests that dreams are a manifestation of our unconscious desires, fears, and unresolved conflicts. Freud believed that dreams serve as a “royal road” to the unconscious mind, where repressed emotions and desires could be expressed symbolically. According to Freud, the images and events in dreams reflect hidden desires or unresolved emotional issues.

5. The Emotional Regulation Theory

Some modern psychologists argue that dreaming plays a role in processing emotions. During REM sleep, the brain’s limbic system is highly active, suggesting that dreaming might help us work through emotional experiences, particularly those that are distressing. This theory aligns with research showing that individuals who experience trauma may have vivid, emotionally charged dreams that help them process difficult emotions.

Common Themes in Dreams

While every dream is unique, certain themes and symbols appear consistently across cultures and individuals. Common dream themes include:

• Falling: Often interpreted as a symbol of insecurity or loss of control.

• Being chased: A common dream reflecting feelings of stress, anxiety, or avoidance.

• Flying: Can represent freedom or a desire to escape from reality or limitations.

• Teeth falling out: Associated with feelings of inadequacy or fear of aging.

• Nudity in public: Can indicate vulnerability or embarrassment.

Many of these recurring themes are believed to represent underlying psychological states, emotional struggles, or concerns that are being processed during sleep.

Can We Control Our Dreams?

For most people, dreams occur involuntarily, but there are instances when people can control the content of their dreams. This phenomenon is known as lucid dreaming—a state in which the dreamer becomes aware that they are dreaming and can exert control over the dream environment, narrative, and actions. Lucid dreaming is a skill that can be developed through techniques like reality checks and dream journaling, and it has been a subject of fascination for both researchers and dreamers alike.

The Role of Dreams in Mental and Emotional Health

Dreams are not just strange experiences that occur while we sleep; they can also serve as a window into our mental and emotional states. People who suffer from conditions like anxiety, PTSD, or depression often experience vivid, disturbing, or recurring dreams that reflect their waking-life struggles. In this sense, paying attention to dreams can help individuals recognize unresolved emotional issues.

Therapists sometimes use dream analysis as a therapeutic tool, helping clients explore the symbolism and emotions in their dreams to gain insight into their unconscious mind. While dream analysis is not a universally accepted practice, it continues to be a popular method in psychotherapy and self-reflection.

Conclusion

Dreaming is a fascinating and complex process that taps into our unconscious mind, offering a glimpse into our emotions, memories, and psychological states. Whether viewed as a random brain activity, a method of processing emotions, or a means of rehearsing for real-life challenges, dreams remain a crucial part of the sleep cycle. Despite decades of research, science still has much to learn about the precise mechanisms and purposes of dreaming. Nevertheless, our ability to dream continues to captivate us, providing a rich, mysterious terrain for both scientific exploration and personal introspection.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.