Hell, the Shaman, and The Planet of the Apes

Myth, Cinema, and the Eternal Return of the Fool

Time bends. Space is... boundless. It squashes a man's ego. I feel lonely. That's about it. Tell me, though, does man, that marvel of the universe, that glorious paradox who sent me to the stars, still make war against his brother... keep his neighbor's children starving?

— Planet of the Apes (1968)

It is the shamanic descent into Hell that promises the evisceration of the journeyman seer—he who would descend to the lower depths by mutilating the self and plumbing the fiery purgatory of the underworld—to bring back the hidden knowledge. Death can be seen as the gateway to a land wherein the future can be foretold, and the Secret Knowledge retrieved to be shared with the tribe—thus averting the catastrophe that prompted the shaman's consultation in the first place.

In Planet of the Apes [1], the classic 1968 science fiction film starring Charlton Heston and Roddy McDowall, the shamanic descent is mirrored in a weird inversion of the monomyth, as outlined by Joseph Campbell in Hero with a Thousand Faces. The threshold stage of the Hero’s Journey is the crash landing in the water—a river of rebirth, a baptism of selfhood—but one that leaves the space voyagers adrift on the edge of a vast desert. Thus, they must “Abandon All Hope, Ye Who Enter Here.”

Taylor (Heston) is revealed to be a rabid misanthrope. Landon (Robert Gunner) and Dodge (Jeff Burton), his companions (Landon could be taken for Jewish, and Dodge is Black, underscoring the film’s subtle racial commentary), are representative of the larger culture and its perception of life and its value. Taylor is the shamanic character who dismisses the company of man. He says, “I can’t help thinking that somewhere in the universe there has to be something better than man. Has to be.” He’s a salty, rawboned, cigar-chomping Sixties cowboy antihero, a cynic and pessimist who strikes out on the Fool’s Journey, making his way through a rocky desert landscape that abuts strangely with a lush, tropical veldt.

Stewart, a fourth crewmember—a woman brought along, presumably, so that the space voyagers (who left Earth at lightspeed, realizing they would warp into the future) could repopulate whatever planet they happened to create a colony on—dies in her sleep due to a problem with her hibernation chamber. She is revealed to the others to be a shocking corpse. She is the Tarot image of Death made flesh, the Trump that bespeaks sudden change. This is the “gateway” to events unfolding later. Next, after a disturbing shriek on the soundtrack—worthy of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre which would come out a few years later—waters come rushing into the downed vessel, forcing our explorers to depart in a lifeboat.

The Hunt

The soundtrack is suggestive of jungle drumming and the clarion call of a horn, signaling the hunt. Taylor (the name suggests the making of a fine human suit—not the savage skin of an animal), along with Landon and Dodge, discovers a tribe of primitive humans eating crops as hunter-gatherers in ragged skins. They are mute (as is Taylor later, shot in the throat), and then the full dawning horror of the situation is revealed when seemingly mutant “ape-men” (they hardly look like pure animal apes) ride up on horses. These are gorillas—the warrior caste of ape society—and they carry shotguns and nets. They capture human prey in what Taylor soon discovers is a perverse inversion of the world, wherein humans are captive to ape-like upright “men” (non-generative).

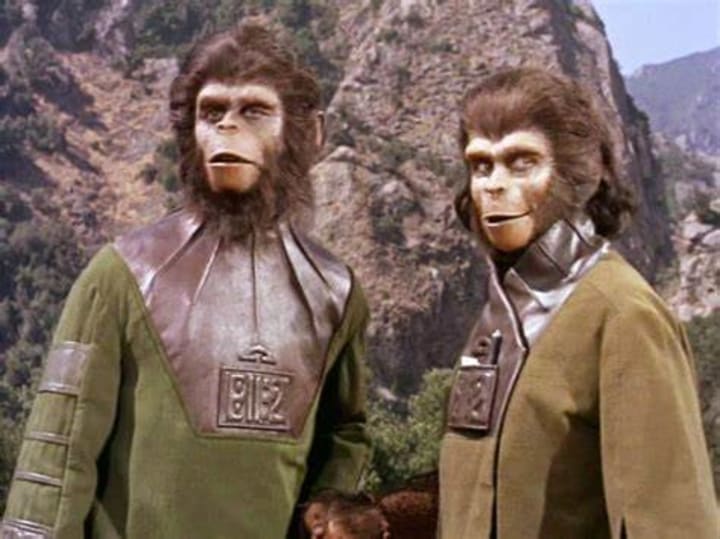

It is a technologically arrested world: horses, buggies, cage-carts. The architecture seems borrowed from The Flintstones or some caveman parody film—carved or even injection-molded stone or cement. The type of environment, perhaps, that a building society of simians might prefer. Taylor is sent to a human zoo—a limbo-like Hell—until rescued by the chimpanzee Zira (Kim Hunter) (the chimpanzees are the scientists and intellectuals of ape society), who recognizes in her “Bright Eyes,” as she calls him, the seeds of genius. She and her husband Cornelius (Roddy McDowall, in a classic, iconic performance) become the “helpers” of Taylor/Bright Eyes (his name altered to reflect his mute status; he now can only see, with an illuminated gaze, the hideous, living oracle of this inverted “madhouse” of a world, as he terms it later).

The Lawgiver

The gorillas are attired in warrior black: leather jerkin-like shirts that most likely serve as armor. They are vaguely reminiscent of Star Trek’s Klingons, in that they serve as the “muscle” of their culture. By contrast, chimpanzees—researchers, scientists, idealists, and intellectuals—wear green: the color of life. The orangutans, attired in brown and beige, might be emblematic of the color of sand—both as in “sands of time” (posterity) and as “stuck in the sand”; i.e., unable to progress due to religious hysteria and terrified adherence to orthodoxy. Dr. Zaius (Maurice Evans) is their chief, and he is a living embodiment of both the terrible, legalistic aspects of The Emperor, as well as those religious fundamentalisms inherent in The Hierophant. But perhaps he is a stand-in, for the Hierophant is obliquely referenced here as the “Lawgiver” who authored the Sacred Scrolls. (The heretical scientist Zira suggests they may not be worthy of the paper upon which they are written—obviously a blasphemous idea.)

Stern tradition, unyielding stagnation, and adherence to past orthodoxies is the bread-and-butter philosophy of the quasi-dictatorial orangutans, who suppress the knowledge unearthed by archaeological digs in the Forbidden Zone.

The Forbidden Zone

Taylor, with the aid of Cornelius, Zira, and Lucius (Lou Wagner)—a chimpanzee stand-in for a discontented Sixties college radical (Taylor tells him at one point, “Keep flying the flags of discontent!”)—strikes off into the aptly named Forbidden Zone to seek out the Great Truth.

Dr. Zaius, the Hierophant image of stagnant tradition, afraid and holding back the Death which promises respite from delusion and the Future, journeys forth after them, carrying with him the black, Devilish energy of the gorillas. A shoot-out ensues—violent wrath and conflict, the Five of Swords—and then the archaeological dig of Cornelius is plumbed, revealing a treasure trove of artifacts: medical prosthesis, false teeth, and a human doll that “talks,” suggesting that the real reality behind the mirrored image of the Ape World is that humans began here as the most advanced species. But it is buried deep in the symbolic subconscious (a real, internal "Forbidden Zone") laid out here like the various stages of hypnotic recall. The rest is a hellish dream of a world and reality turned upside-down. [1]

Dr. Zaius is held hostage, bound and tied to a rock—symbolically inverting the Promethean deity chained for bringing knowledge to tiny, struggling man—arrested by a gun-wielding Taylor, his speech now restored, who brings Nova (Linda Harrison, a mute human) with him. She is now the High Priestess, the role being conferred upon her, transformed by Taylor who kisses the former bearer of the title, Zira.

Cornelius reads in a quiet, powerful scene from the Sacred Scrolls. It is pregnant with bitter, ironic satire and philosophic pessimism:

Beware the beast Man, for he is the Devil’s pawn. Alone among God’s primates, he kills for sport or lust or greed. Yea, he will murder his brother to possess his brother’s land. Let him not breed in great numbers, for he will make a desert of his home and yours. Shun him; drive him back into his jungle lair, for he is the harbinger of death.

The High Priestess is the female aspect of the Divine. Here, Nova is mute—a place beyond mere understanding, in which vocalization is unnecessary. Riding along the beach, the final sound being the sea lapping against the shore (the sea, the “giver of life” from which the evolutionary cycle began), Taylor discovers the hideous truth: he’s been “home” all along. The Statue of Liberty (the Tower Trump of turbulence and disarray, confusion) is revealed in the final, shocking scene—ruins, the aftermath of an implied atomic war. Taylor breaks down, giving vent to an expletive-laden outburst. The end.

But not so. The Fool, the Hero, has journeyed forth—but has not returned. Will not return. Not in Taylor’s lifetime. The shaman never emerges from this personal hell, and brings no reward for the tribe, who are as mute and lost as they ever were.

Tales from the Time Loop

The title of this section is inspired by the title of a 2000 book by New Age conspiracist David Icke, and it makes sense insomuch as the film series of the original Planet of the Apes is a recursive loop. The second film, Beneath... gives us A-bomb-worshipping mutants below the Earth, in a place where illusion is foisted upon the weak-minded. The illusion represents the façade of a world poised on the brink of nuclear destruction, believing itself sane in the face of its religious and political bondage to old, outmoded, and destructive ideals.

The next film, Escape from..., gives us Cornelius and Zira using Taylor’s crashed ship (The Tower, the turbulence of the age) to rocket backward through time to an ancient Earth—Earth in the Seventies—where it becomes politically expedient for the government to try and assassinate them. The next film, Conquest..., presents a bizarre contemporary (1972) world of mutant ape-like slaves, in which the offspring of Cornelius and Zira (McDowall playing his ape son) leads a revolutionary rebellion of his people, echoing the radical sentiment of an era when racial injustice and political authoritarianism were being strongly questioned and opposed.

Thus, the film, which ends with the overthrow of human society, doubles back on itself like the snake eating its own tail. The final film, Battle..., is not one we have yet seen.

Taylor never emerges from Hell. The divine revelation of this timeline is that man is doomed to repeat the same cycle endlessly: evolution from apes, advancement, struggle and conflict, war, self-annihilation, and a handing-over of his atrophied abilities and ingenuity to his ancestral forebears in the form of simian life. They take him as a pet. It is both commentary and allegory: on how man treats the lesser creatures, and on how he lives with and hunts—himself.

“Does man still make war against his brother?” Heston asks as the film begins.

He receives a mute and knowing reply from the vastness of space and the fullness of a time that loops, over and over again, into the One Myth—Promethean, and infused as it is with both tragedy and despair.

Notes

[1] Based upon the science fiction novel by French author Pierre Boulle (The Bridge on the River Kwai). Screenplay by Rod Serling, and is redolent of his “O. Henry” twists and science fiction as social commentary. The term “Forbidden Zone” obviously echoes the “Twilight Zone,” each suggesting a liminal space that is neither upside down nor right side up. Directed by Franklin J. Schaffner. Produced by Arthur P. Jacobs.

[2] The cliffside cave can be seen as a symbolic mind. At the deepest levels of the excavation, the subconscious begins to hold forth with the human history of man, who has been rendered a mute, incommunicative animal. The symbolism of the “talking baby doll” as a threat to the animal or ape order cannot be overlooked. At the end, Zaius, to maintain the social hierarchy and order established by the Sacred Scrolls of the Lawgiver, has the cave dynamited—violently closing off access to knowledge and understanding. He calls off the gorillas in their pursuit of Taylor and Nova, understanding now that the past, the subconscious level of understanding, has been reburied. Taylor the Fool will forever be embarking on a journey that returns, as Poe termed it, to “the selfsame spot.”

Suggested Reading

Boulle, Pierre. Planet of the Apes. Translated by Xan Fielding, Vanguard Press, 1963.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press, 1949.

Twitter/X: @BakerB81252

My book: Cult Films and Midnight Movies: From High Art to Low Trash Volume 1.

Ebook

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.