Imagine a scenario where — tiny living robots work inside of your body, sensing and delivering life-saving drugs, or deploying them out to hostile environments, from the sea to even outer space, again, sensing and delivering and monitoring various useful things [15,6]. But even more interestingly, imagine if these robots were actually living bacteria, such as E.coli? As far-fetched as this may sound, the reality is probably a little closer than you think. In the realm of IoT, or more precisely, the Internet of Bacterial Things (IoBT), researchers have been making advances in making this into reality.

IoBT is about using networks that mix biological entities and nano-scale devices to communicate. Thanks to advancements in synthetic biology and nanotechnology, IoBT has a lot of possible uses. Scientists are exploring using bacteria as one of these bio-nano components. For instance, in the realm of environmental sustainability, these bacteria could be programmed and sent to various places to detect toxins and pollutants, collect information, and even help clean up the environment through natural processes.

Similarly, in the field of medicine and healthcare, bacteria could be engineered to help treat diseases [2]. That’s all well and good, and using these so-called workhorses of biotechnology to brew valuable materials is not new. Yet in the context of IoBT, something interesting happens when you treat bacteria as connectors.

Bacteria as IoT Device

By carrying DNA that contains useful hormones, these bacteria could navigate to specific areas within the human body. Once they reach their destination and are triggered by their internal sensors, they can produce and release these hormones. These potential applications aim to harness the sensing, triggering, communicating, and biological processing capabilities of bacteria, which interestingly resemble the components of typical computer IoT devices. This suggests that bacteria could be seen as a living version of an Internet of Things (IoT) device. Consequently, this shift in the perception of bacteria opens up an exciting area for exploration in the field of bio-design and bio-HCI (human-computer interaction) [11].

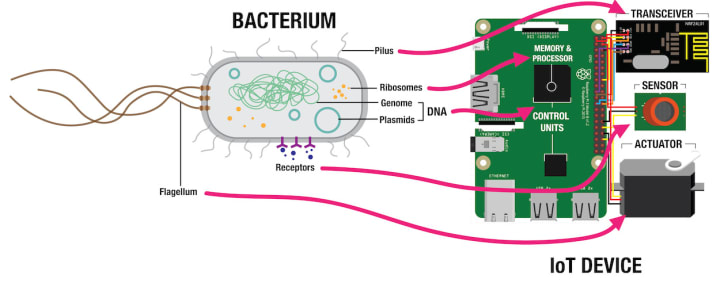

Perhaps the easiest way to explore the role of bacteria in IoT in a meaningful way, is to compare microbes with existing computerized IoT devices in the field (fig. 1). This way, the features of bacteria can be compared against standardized digital models, and allow better appreciation of the species’ attributes and drawbacks.

In Akyildiz et al. [2], an illustration depicting the shared elements of a generic biological cell and a typical IoT device was presented. Here, we narrow the image further. Fig. 1 illustrates an E.coli bacterium (hereafter called ‘bacteria’), and Raspberry Pi with add-on components, to represent the biological and digital worlds. They were deliberately chosen for this paper, as they are the common, standardized ‘workhorses’ of DIY biology and open-source computing, respectively.

And as such, they both make an ideal candidate to be a cost-effective and accessible tool for meaningful engagement and learning. Overall, whilst we acknowledge the over-simplification of both the digital and biological worlds in Fig. 1, the illustration is designed to raise important questions on how bacteria could be programmed and applied in real-life scenarios. These questions may arise from not only the practical differences in stability, responsiveness, and even safety of interaction, but also from the future ethical implications of Internet of Bacterial Things (IoBT) may have on our society.

Bacterial Sensors and Actuators

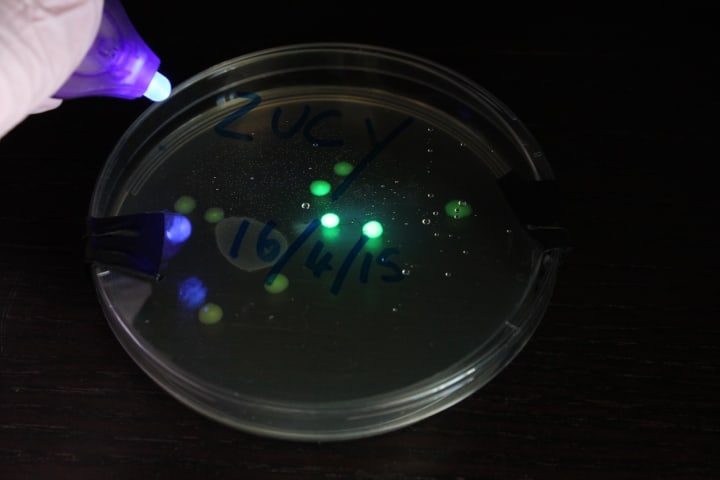

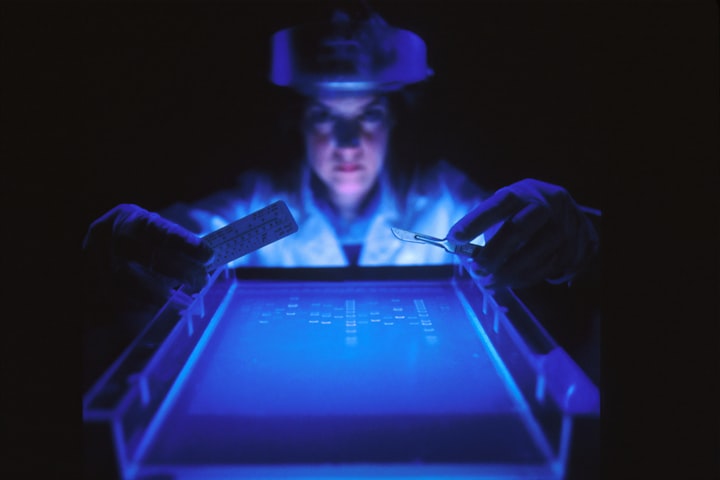

Bacteria can sense a wide range of stimuli, such as light, chemicals, mechanical stress, electromagnetic fields, and temperature, to name a few. As a response to these stimuli, bacteria may interact through movement using their flagella (fig. 2), or through the production of proteins, including coloured pigments such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) (fig. 3).

Given the molecular nature in which bacterial sensors and actuators operate, there can be major differences in their responsiveness, sensitivity, and stability, compared to their digital counterparts.

Bacterial Control Unit, Memory, and Processor

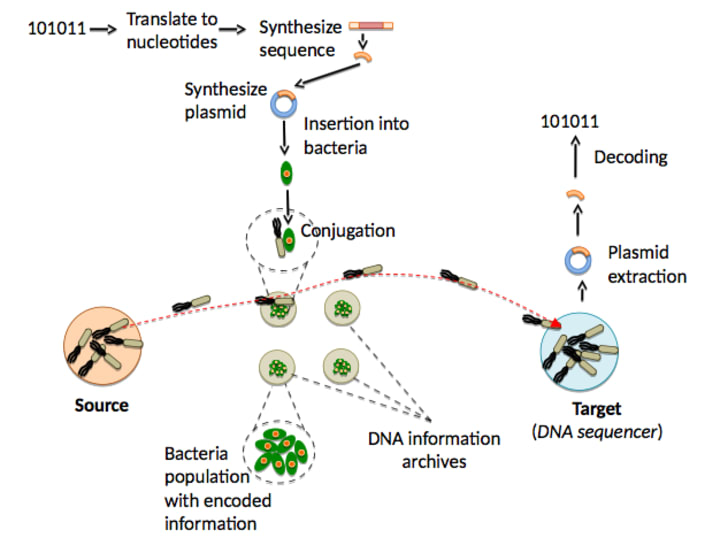

The DNA inside the bacteria offers storage of data and encodes instructions that can be translated into viable functions. And as such, it offers similar roles as a computer’s control unit (e.g. as an entity managing ‘data units’ and software conditional expression units), memory (e.g. storage of embedded system data), and the processing unit (e.g. executing software instructions). There are two main forms of DNA present in the bacteria, first as genomic DNA, containing most instructions for cell functioning, and second as smaller circular units called plasmids. In synthetic biology, plasmids are often used to introduce a wide range of genes into the organism, making it a versatile tool for function customization and storage of new data.

Bacterial Transceiver

As a component designed to allow both the transmission and reception of communication, the cellular membrane of bacteria can be considered as a transceiver. It is involved in the release and import of molecules as part of cell signaling pathways. Additionally, the bacterial pilus (fig. 1) is used for the conjugation process between two cells which results in DNA exchange. Overall, such types of communication are referred to as molecular communication, which forms the basis of bacterial nanonetworks.

Bacterial Nanonetworks

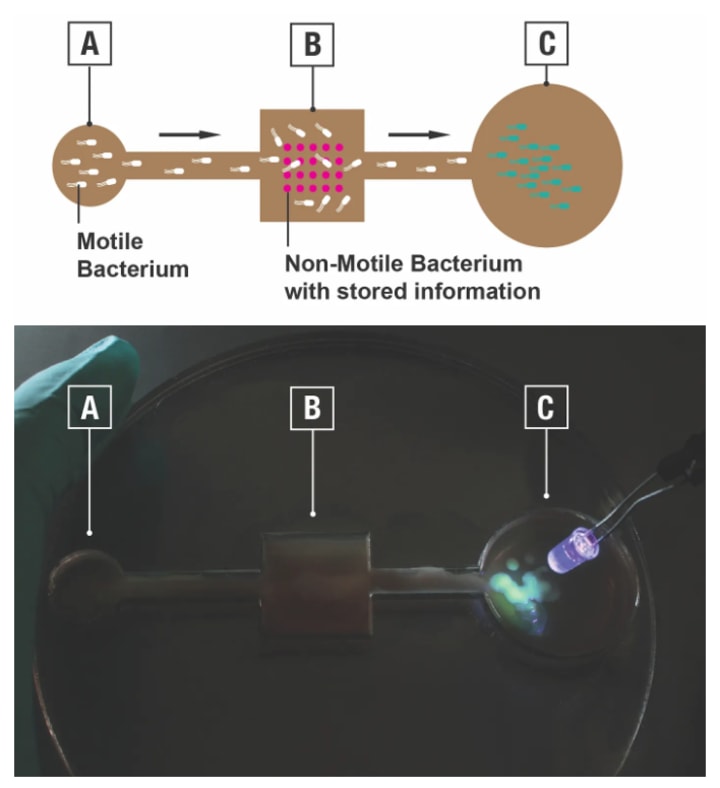

Bacterial nano-networks are an example of molecular communication, which has been gaining increasing attention in the IoT community [1,2,5]. Bacterial nanonetworks involve communication between bacterial communities through molecular signaling [19], and as discovered recently, through electrical fields [13]. Another communication method is through physical movement: This involves harnessing the motile ability of bacteria, such as E.coli, to act as information carriers.

In such cases, the digital information is translated into DNA which can be transformed into bacterial cells and later decoded back to the digital format. An example of its implementation, which involves conjugation between non-motile and motile bacteria, to store and transport DNA data, was demonstrated by Tavella et al. [16] (fig. 4, 5).

Challenges and Possible Pathways

Despite the rich framework that bacteria bring in HCI investigations, working directly with the micro-organisms may bring practical and ethical challenges. Given its biological nature, handling, and manipulation requires careful consideration, which do not necessarily need to be addressed when working with computers and electronics. These include potential professional supervision, license to handle some microbes safely and legally, cost implications, and the bioethical and biosafety challenges that may arise.

Furthermore, HCI investigators may not be familiar with bacteria and have no previous working knowledge in the field, which may pose challenges in meaningful engagement. This will be compounded by some of the fundamental concepts of bacterial physiology which can appear abstract to those without prior knowledge. To overcome these challenges, we propose to leverage potential HCI investigations on the DIY biology movement and gamification to aid the process. Below we outline them in further detail and explain our rationale.

DIY Biology

The DIY Biology movement promotes increasing accessibility and affordability of tools, data, and materials of biotechnology [9]. It capitalizes on the changing economic landscape of the modern biotechnology industry, represented by the continually declining cost of DNA synthesis and sequencing. Currently, tools and techniques to run small-scale experiments with micro-organisms are widely available to the general public, through various channels, including maker spaces.

Furthermore, there are supportive kits too. Educational products such as Amino Labs [3] cater specifically to those interested in manipulating and genetically engineering E. coli species. It allows the creation of customized colors from bacteria, through building genetic circuits that can be triggered from a range of environmental stimuli.

Bacteria, especially E.coli, make an ideal tool for biohacking projects, given that they are easy to acquire, culture, and maintain. The industry standard strain K-12 E.coli, for example, which is used in Amino lab, is relatively safe to handle. They have been engineered to be non-pathogenic and difficult to spread outside of the laboratory environment. Unlike most species of bacteria, the K-12 strain can be purchased relatively easily in the U.S. and most parts of Europe.

Gamification of Bacteria

In the context of IoT, gamification has shown several benefits. For example, it has been shown to increase engagement of new IoT applications [4], and positive shifts in human behavior (eg. travel behavior as part of a Smart City initiative [12]). Similarly, Wood et al.’s GPS Tarot is a playful, artistic tool that allows participants to learn and become aware of ‘hidden technologies’ in the form of embodied Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) satellites [18,19].

In a similar vein, we hypothesize that gamification of E.coli can aid in engagement, learning, and attitude shifts in their integration in HCI and IoT investigations. Micro-organisms have been gamified before, as a form of a biotic game, which is a hybrid bio-digital game that integrates real microbes into computer gaming platforms [14]. Overall, the gamification of microbes has proven successful in terms of engagement, playing experience, and learning [7,8,10].

Ethical Discourse

As with any potential IoT applications, ethical considerations and privacy issues in relation to user data would also apply to bacteria-driven IoT systems. Interestingly, however, due to the biological nature in which such systems can operate, additional layers of ethical challenge are presented. Firstly, one of the challenges stems from the autonomous nature in which bacteria can function. As they can evolve and behave autonomously, they could pose a threat to natural ecosystems and even become pathogenic. This may not apply to educationally-deployed K12 E.coli strains of course, but nevertheless, the possibility is worth considering from a wider perspective.

Secondly, bacterial nano-networks rely on the transfer of data (encoded in DNA) through a natural process of conjugation and cell motility. Although highly engineered bacteria may provide efficient communication systems, ultimately, they are biological entities, which can produce unexpected outcomes (e.g. mutations). All in all, whilst the use of bacteria in IoT and HCI offers exciting opportunities, they also present fresh ethical challenges, which provide extra paths for discourse.

In Conclusion…

In this paper, we have highlighted features of E. coli bacteria that could enable rich exploration of microbes in the context of IoT and HCI. This was initiated by a comparison of the organism with a conventional computer-driven IoT device. Furthermore, we have highlighted the current lack of tangible infrastructure for researchers in IoT and HCI to access and experiment with bacteria. As a potential solution, we have proposed to utilize the DIY biology movement and gamification techniques to leverage user engagement and introduction to bacteria. And finally, we have outlined the ethical challenges that bacteria-driven IoT systems may pose, which are brought on by the autonomous and biological (and therefore unpredictable) nature of bacteria. Such challenges offer a rich area for discussion on the wider implication of bacteria-driven IoT systems.

References

[3] Amino Labs.

[4] Charlton and Poslad. 2016.

[6] Gotovtsev and Dyakov, 2016.

[10] Lee et al., 2015.

[11] Pataranutaporn et al., 2018.

[12] Poslad et al., 2015.

[14] Riedel Kruse et al., 2011.

[16] Tavella et al., 2018.

[17] Wood et al., 2017a.

[18] Wood et al., 2017b.

[19] Zhang et al., 2015.

About the Creator

Raphael Kim

Stories on microbes, DNA & AI 🦠🧬 🤖 Sign up to my newsletter for Biodesign & Sustainable Design stories: https://www.biodesign.academy/subscribe

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.