Building Resiliency Amidst Crumbling Sea Walls Through Green Infrastructure

Using Mangroves to reduce flooding

Abstract: The 2017 Global Climate Risk Index, rated Mozambique as the country with the greatest climate risk in 2015. This is due to flooding, which left the Northern portion of the country without power for three months. Mozambique was rated 22nd for the whole period between 1992-2015. Northern Mozambique is expected to see more intense flooding as climate changes progresses. Here the focus is on the coastal city of Angoche, in the province of Nampula in Northern Mozambique. The city was originally part of an Arab sultanate. Angoche resisted conquest until 1910. Angoche has a distinct language, eKoti, and is relatively isolated from the provincial capital, 200 km to north because it lacks a tarred road. Most of the city’s infrastructure dates from the colonial era and much of it is crumbling. It is unlikely that the physical infrastructure will be repaired in a timely manner. The floods in 2015 destroyed 10 of the 12 bridges on the main roads between Angoche and the capital and by 2016 only one of the bridges had been repaired. The city must increase its resiliency if it is to survive. The city’s best hope may be to shore up its crumbling brick and mortar infrastructure with green infrastructure in the form on mangroves and conservation agriculture. These strategies will adapt to and mitigate climate change by reducing the severity of flooding, while simultaneously sinking carbon and increasing the city’s food security.

Introduction: Angoche is a coastal city in Northern Mozambique in the province of Nampula. The town is about 250 km south of the Island of Mozambique where Vasco de Gamma landed in 1498, but the Arab Sultanate in Angoche resisted conquest until 1910. The city’s power resided on it unique harbor, ideal for Arab trading dhows, but too shallow for Portuguese warships to bombard the city. The shallow harbor is protected by mangroves, which surround the cost line. Beyond the mangroves the city is surrounded by a coral reef. The reefs are dotted with a chain of islands that has been rapidly disappearing and losing its vegetation in recent years. The reef and the mangrove forest are monitored by a partnership between the WWF and CARE, which maintains an office in Angoche because of its unique ecosystem. The protective mangroves have been threatened by unmanaged harvesting of the trees for timber. Massive floods, which hit the country in 2015, destroyed 12 bridges between the provincial capital and Angoche forcing vehicles to travel an alternative route over sand roads, which takes 5 hours to travel 200 km during the dry season and 10 hours during the raining season. The 2017 Global Climate Risk Index, which analyzes how countries have been affected by weather events using the most recent data from 2015, rated Mozambique as the highest affected country. This is due to torrential flooding, which left the Northern portion of the country without power for three months. Mozambique was rated 22nd for the whole period between 1992-2015 (Kreft 2015). Angoche has been inundated multiple times in the last 20 years.

The climate of Angoche is costal and tropical. It is characterized by a long dry season from April to December. The population is supported primarily by artisanal fishing and rain fed agricultural. Northern Mozambique is at greater risk for flooding as a result of climate change (Hirabayashi 2010). The infrastructure of the city has been hard-hit snice independence. The city will need to improve its resiliency in to protect against increasing flooding in the future. Angoche lacks the funds to rebuild its brick and mortar infrastructure, but the city can improve its resilience through green infrastructure. Angoche can build resiliency through mangrove planting projects and conservation agriculture. Mangrove planting projects to replenish the stands of mangroves will help to reduce flooding from storm surges, while providing habitats for marine life and sinking carbon. Conservation tilling, as opposed to the traditional slash and burn agriculture, will increase the soil’s ability to hold water, while reducing erosion, increasing soil quality, and sinking carbon. Focusing on replenishing Angoche’s green infrastructure provides a relatively low-cost way for the city to mitigate and adapt to climate change, while increasing its food security.

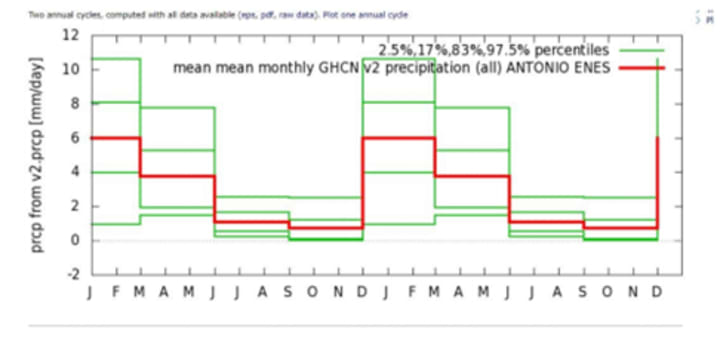

Case Study of Angoche: The coastal city of Angoche is characterized by a rainy season and a dry season. The KMNI Climate Explorer lists Angoche under its colonial name Antonio Enes; these figures use data from the Antonio Enes weather stations from 1917 to 1996. The data shows that on average the city receives practically all of its precipitation during the rainy season from December to May (below).

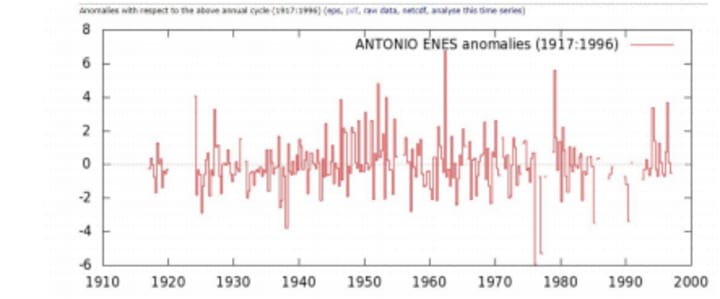

The Majority of the rain comes between December and March. The rainy season is driven by the southern migration of the ITCZ (Parker 1995). Angoche has historically suffered periodic floods. The image below shows anomalies from 1917 to 1996. The breaks during the 90s represent the civil war (Below). The break in data makes it impossible to definitively say there is a trend of increasing flooding in Angoche, however the region at large is expected to see an increase in flooding due to climate change (Hirabayashi 2010). In 2015 Mozambique suffered devastating floods, which shot it to number one for the yearly climate risk index (GLOBAL CLIMATE RISK INDEX 2017). The 2015 floods devasted the infrastructure of Mozambique as a whole and left the Northern portion of the country without power for 2 months. The graph below shows that suffered 79% of households in Angoche suffered flood related shocks in 2015 (Peham 2017, pg 24). Even if flooding does not increase due to climate change the current climate produces more intense floods than the existing infrastructure can sustain.

The addition of green infrastructure can help reduce the burden of flooding related shocks for Angocheans in the current and future climate. Climate Change in Angoche: The IPPC acknowledges that although flooding is seen as of one the critical consequences of climate change there are few papers which tackle changing in flooding patterns because of the difficulty in modeling extreme flows. Unlike droughts which may last for years, flooding occurs on an acute time scale. It is difficult to accurately model and analyze daily results from climate change projections. (IPPCC 2001). To attempt to understand how flooding will change in Angoche, models of temperature change in East Africa and daily river discharge are useful. Models which examine annual precipitation are less useful for predicting flooding because increases or decreases in the mean do not necessarily correlate with changes in extreme weather invents.

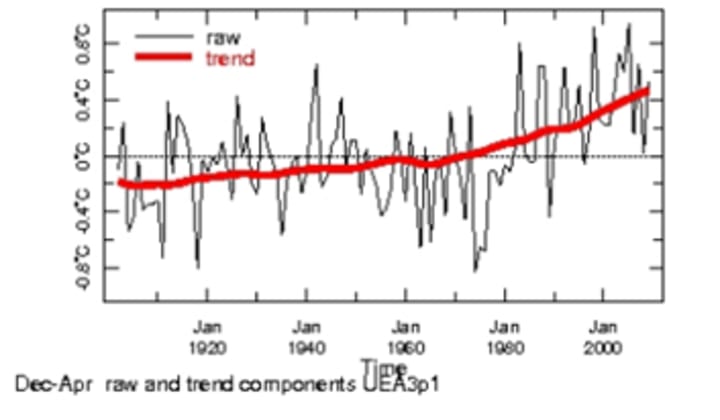

Trend analysis from the IRI map room (above) shows an increase in temperature in the region. The trend explains 24% of the increase and is significant at 1%. An increase in temperature should lead to an increase in the intensity of storms and a consolidation of precipitation in more extreme events as the atmosphere will hold more water vapor before it condenses.

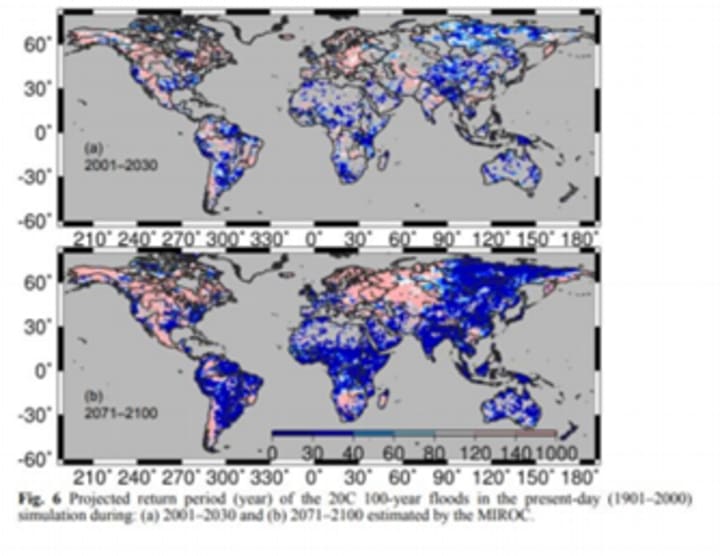

Hirabayashi et al’s study found that Eastern Africa, is expected to see an increase in flooding (below). The projections from Hirabayashi’s et al, study are from the output a climate change simulation from the Model for Interdisciplinary Research on Climate (MIROC). The Maproom trend on monthly temperature from East African Weather Stations from 1920 to 2000 MIROC is general circulation model which has sub modules for ocean, land and air surfaces. The model is used to demonstrate extremes in daily discharge of river basin.

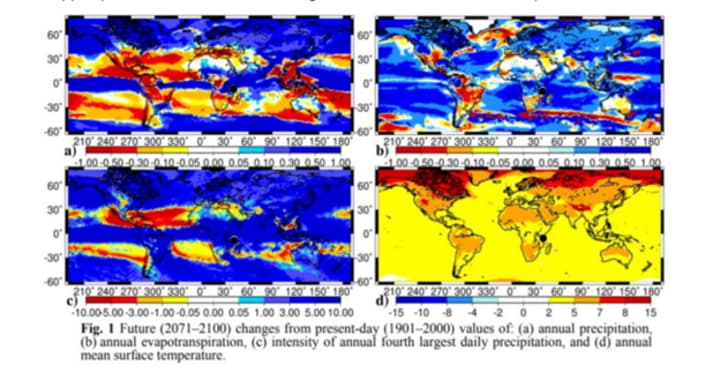

The model is granular to 1.1 degrees. The granular nature of the model produces higher accuracy and allows the model to estimate daily discharge from smaller river basins. The model’s ability to project daily discharges on a granular level is of critical importance for estimating flood. Monthly precipitation models are apt to lose flooding events in the averages (Hirabayashi 2010). It is important to note that MIROC return the highest temperature of the IPPCC models, because large ice albedo feedback and reduced ocean heat up. The interaction between increasing temperature and the acceleration of the water cycle mean that MIROC projections of water cycle extremities may be extreme. The model also uses a scenario of high economic growth, with middling technological innovation, and continued fossil fuel use. In other words, the model projects changes in flooding using daily river discharge as a proxy, assuming relatively high positive feedback from albedo change in ice, low ocean heat uptake and continued global economic expansion fueled by the growth of fossil fuels without breakthrough technologies. The figure below shows the results of Hirabayashi’s et al analysis. Angoche’s approximate location has been indicated by the black dot for reference. As the figure shows Angoche is on the borderline for changes in precipitation, and may see its annual precipitation increase or decrease, the same is the case with evapotranspiration, but it is clear that in this scenario the model projects that Angoche will experience increase in intensity of the fourth largest daily precipitation event and between 2-5 degrees of increase in mean annual temperature.

Hirabayashi’s study validated the flood data in two steps. The first step compared the annual maximum daily discharge of river gages to the model in basins where this data was available from 1901- 2000. The second step compared the registry of disastrous floods to the output from the model. This comparison found that the simulation correctly identify most of the disastrous floods in the registry. The data from the model and the offline simulation was then used to estimate the frequency of so called 100 year floods in the present day conditions between 2001 and 2030, the model then estimated the frequency of 100 year floods between 2071-2100 using the MIROC (Hirabayashi et al 2010). For the region including Angoche MIROC estimated that 100 year floods could be expected to return within 30 years. (Image right Hirabayashi et al 2010). Given the current state of Angoche’s infrastructure and inability to cope with flooding the city will need to improve its resilience to cope with a higher frequency of intense flooding.

Building Resiliency: When Angoche was inundated by the 2015 floods the roads in the neighborhood Inguri of became deep rivers and most of the homes were submerged up to their rooves. The low-lying neighborhood of Inguri gives way to crumbling sea walls, mangroves and mandioca fields. The city is unlikely to obtain the funds and expertise to maintain, let alone expand its sea walls, but it can increase its resiliency by strengthening its mangrove forests and training its small holder farms to employ conservation agriculture methods. In addition to improving the city’s resilience the mangroves and conservation agriculture will sink carbon and improve the town’s food security. Mangrove trees which line the shores of Angoche provide critical habitat to fish and serve as a shore break.

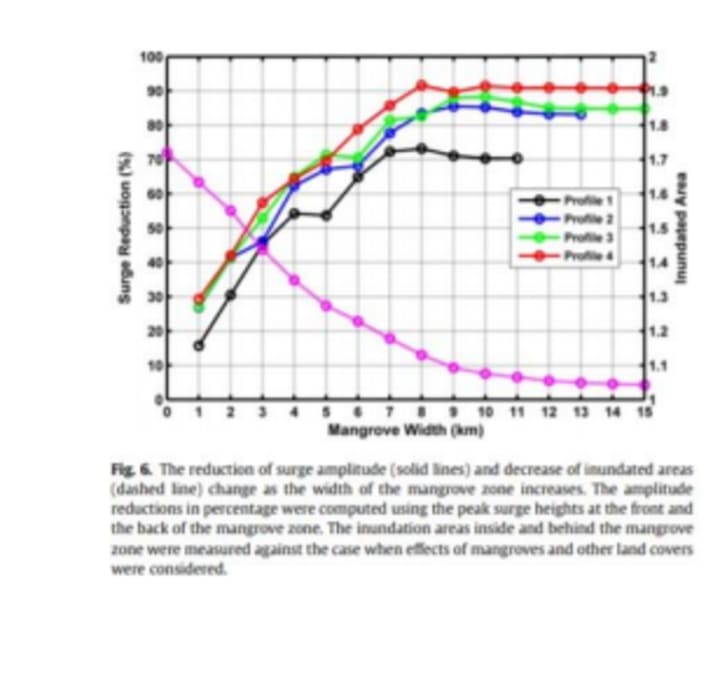

The Mangrove trees have been diminished by unregulated harvesting of trees for fuel woods and construction materials (Byers 2012). Mangroves can dramatically decrease the storm surge of hurricanes as intense as a category three (Zhang 2012). Zhang et al found that a 1km wide mangrove forest can reduce storm surge by 30% while studying the protective effects of mangroves on Flordia’s coast during Hurricane Wilma (Category 3 for Florida landfall). The pink line in the image below, from Zhang’s study, shows the percentage of land inundated, while the other lines show the reduction in storm surge under different scenarios. The reduction in storm surge and land inundated continues to expand with the width of mangrove forests. An 8 km wide mangrove forest could reduce storm surge of a category three hurricane by up to 90% (Zhang 2012).

Depending on the site’s conditions there are two viable options for mangrove rehabilitation and expansion around Angoche. Both cost roughly $100 a hectare (Lewis 2001). The preferred method is ecological restoration, where conditions for mangroves to naturally regenerate from neighboring mangroves are facilitated. This process is generally the cheapest and most successful. Where ecological mangrove regeneration is not possible it is possible to regenerate mangrove stands through planting saplings. This method also costs roughly $100 a hectare; however, it has a much higher failure rate. Mangrove restoration as a primary method of coastal protection has already been adopted in Quelimane Mozambique, a few hundred km south of Angoche as the primary infrastructure to protect the coast line (Byers 2017). A similar large-scale mangrove restoration project, perhaps facilitated by WWF-Care as they have worked with the community reduce mangrove harvesting (Primeras and Segundas 2015), in Angoche could dramatically decrease flooding in at risk neighborhoods like Inguri, while simultaneously increasing the habitat for fish, which provide a vital protein source for the community. Conservation agriculture can also help reduce flooding in Anogoche. WWF-CARE has trained community members to farm using conservation agriculture. This means reducing swidden (slash and burn) agriculture and encouraging the planting of cover crops like legumes, which increase the nitrogen content of the soil. Incorporating crop residue and planting cover crops also increases the carbon content of the soil, which sinks carbon, while increasing the soil’s ability to hold moisture and nutrients. Increasing the soils ability to hold water means that during flooding or heavy precipitation the soil absorb more water allowing corps to survive flooding events (Primerias and Segundas 2015). The soil’s ability to hold water also reduces flooding by acting as a temporary reservoir for water (Kassam 2015). The ability of corps planted under conservation agriculture to survive floods and hold water will reduce the flooding related shocks in Angoche and supplement the protection offered by mangrove replanting.

Conclusion: Eastern Africa is expected to see an increase in flooding if current conditions persist as shown in Hirbabayashi’s models. Anogche has been inundate under existing conditions several times. In 2015 79% of the household in Anogche experienced flood related shock. The city is unlikely to acquire the funds to repair and upgrade its brick in mortar infrastructure. Green infrastructure in the form of mangrove forest rehabilitation and conservation agriculture can provide the city with protection from flooding, while sinking carbon and increasing the city’s food security. The efforts already being implemented to a small degree by CARE-WWF in Angoche should be continued and expanded to improve the city’s resiliency in the face of climate change.

References:

Asante K, Brito R, Brundrit G, Epstein P, Nussbaumer P, & Patt A (2009). Study on the Impact of Climate Change on Disaster Risk in Mozambique.

INGC Synthesis Report on Climate Change - First Draft, National Institute for Disaster Management, Maputo, Mozambique (February, 2009) http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/9007/. Byers, Bruce. “Mangroves in Mozambique: Green Infrastructure for Coastal Protection in an Era of Climate Change.” Bruce Byers Consulting, Sept. 2012, www.brucebyersconsulting.com/mangroves-inmozambique-green-infrastructure-for-coastal-protection-in-an-era-of-climate-change/. “Restoring Mangroves in Mozambique in an Era of Climate Change” October 2017, http://www.brucebyersconsulting.com/restoring-mangroves-in-mozambique-in-an-era-of-climatechange/.

Ehrhart, Charles, and Michelle Twena. Climate Change and Poverty in Mozambique Realities and Response Options for Care. Care International Poverty-Climate Change Initiative, Dec. 2006, www.vub.ac.be/klimostoolkit/sites/default/files/documents/climate_change_and_poverty_in_mozambi que-country_profile.pdf.

HIRABAYASHI, YUKIKO, SHINJIRO KANAE, SEITA EMORI, TAIKAN OKI & MASAHIDE KIMOTO (2010) Global projections of changing risks of floods and droughts in a changing climate, Hydrological Sciences Journal, 53:4, 754-772, DOI: 10.1623/hysj.53.4.754 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1623/hysj.53.4.754?needAccess=true IPPC, Hydrology and Water Resources, 2001, www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/tar/wg2/index.php?idp=171.

Kreft, Sönke, et al. “GLOBAL CLIMATE RISK INDEX 2017 Who Suffers Most From Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2015 and 1996 to 2015.” germanwatch.org/fr/download/16411.pdf. Lewis, Roy R. Mangrove Restoration - Costs and Benefits of Successful . . Beijer International Institute of Ecological Economics, 4 Apr. 2001, http://www.fao.org/forestry/10560- 0fe87b898806287615fceb95a76f613cf.pdf .

A. Kassam, R. Derpsch, T. Friedrich, Global achievements in soil and water conservation: The case of Conservation Agriculture, International Soil and Water Conservation Research, Volume 2, Issue 1, 2014,Pages 5-13, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-6339(15)30009-5.

Jury, M. R., Parker, B. A., Raholijao, N. and Nassor, A. (1995), Variability of summer rainfall over Madagascar: Climatic determinants at interannual scales. Int. J. Climatol., 15: 1323-1332. doi:10.1002/joc.3370151203 Parkinson, Verona. “Climate Learning for African Agriculture: The Case of Mozambique.” https://www.nri.org/images/Programmes/climate_change/publications/WorkingPaper6Mozambique.p df. Page 35

Peham, Andreas. NACC Final Evaluation Report . CARE International in Mozambique, 29 Nov. 2017, careglobalmel.care2share.wikispaces.net/file/view/Nampula+Adaptation+to+Climate+Change+Final+Eva luation.pdf. Page 24

Pomeroy, Carlton, and Antonio Alijofre. “Conservation Agriculture as a Strategy to Cope with Climate Change in SubSaharan Africa: The Case of Nampula, Mozambique .” 2012. “Posts about Mangroves on Primeiras & Segundas.” Primeiras Segundas, WWF-CARE, 2015, primeirasesegundas.net/category/mangroves/. “Temperature Time Scales.” Climate Data Library, IRI Time Scales Maproom, iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/maproom/Global/Time_Scales/temperature.html?bbox=bb%3A24.16%3A29.91%3A51.97%3A-9.68%3Abb®ion=bb%3A24.16%3A-29.91%3A51.97%3A9.68%3Abb&seasonStart=Dec&seasonEnd=Apr.

“ Time Series Monthly ANTONIO ENES GHCN v2 Precipitation (All).” Climate Explorer: Time Series, climexp.knmi.nl/getprcpall.cgi?WMO=67273.2_mean4_anom&STATION=ANTONIO_ENES.

Zhang, Keqi, et al. “The Role of Mangroves in Attenuating Storm Surges.” The Role of Mangroves in Attenuating Storm Surges, Estzuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2012. http://www.evergladeshub.com/lit/pdf12/ZhangK12-EstuCoastShelfSci102.11-23-MangrStorms.pdf

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.