Wendigo's Moose

Part one of the Bone Crushers series

South of Saskatoon in Southern Saskatchewan, fertile farmland produces megatons of wheat and other food crops yearly. This story doesn’t take place there. North of Saskatchewan the fallow soil of the subarctic tundra grows stubby grass, moss, and lichens. This story doesn’t take place there either. Between those two tracts of land is a six-hundred-mile-wide stretch of boreal forest in the midst of winter’s grip. Now there’s a place for a story.

In the upper reaches of that forest, just north of the Fon Du Lac River, Robér chambered a shell into his 30.06 Springfield with an icy snick of cold steel. The shell had just been in there, and he had just racked it out. He pointed the rifle at imaginary targets out in the forest, a forest which normally ran amok with moose this time of year. Yet Robér hadn’t seen one in days, and they were hard to miss, standing six feet at the shoulder. This particular forest had a vast scarcity of moose—it was moose deprived. It had less moose than were on the moon. A man with no fingers, no toes, and poor counting skills would have no trouble tallying up the number of moose in this forest. Robér leaned back against an ancient Jack Pine in a hunting blind, scratched under his deer-pelt hat, and turned to his hunting partner, Claude. “Ya reckon they all left, aye?”

“I don’t reckon.” Claude said, and kept his dark eyes scanning left to right through the optics on his .308 Winchester. No moose would come within his gaze and not be in danger of a sudden volley of lead. Claude stood a few inches taller than Robér and was a few inches tighter around the waist. He always stared at you with one eyebrow cocked as if he were questioning everything you said. Both men had close-cropped beards. Robér had a habit of scratching his absent-mindedly. Both men wore animal-hide parkas, gloves, pants, and boots.

Robér propped his rifle against a mossy log, losing interest in non-existent moose. He gulped cold, bitter tea out of a thermos and thought of his wife, Mary and her soft brown hair, perpetual half-smile, and strong fingers that could rub out the tightest muscle cramps or tease his ears with a feathery touch. His stomach grumbled; he could almost smell her strong black tea, fresh bread, and pickled walleye, waiting back in the log house. He wanted to go home, but he knew he couldn’t. That wasn’t the way of Métis men—to go home empty-handed—even if he was only half Métis due to his mother being a white woman from Ontario, which explained his green eyes. Métis men provided for their families from the land. Had done so for millennia. Robér and Claude, now in their mid-thirties, were accomplished hunters, but food on the hoof didn’t always cooperate, and you could never know for sure where it roamed at any given time.

Robér’s ancestors had lived and hunted in these forests for at least ten thousand years according to the elders. He knew many of the ancient stories; stories that had never been written down; stories his father had told him of the important spirits that dwelled in these forests. Robér and Claude were officially Catholics, but they never gave up the old ways, the old beliefs—they simply honored both. His father had said you needed to respect the spirits, or you’d never bag a moose. If you really pissed off the spirits, he had said, the moose might bag you. Some days the spirits were friendly, others they were ambivalent or downright mean. His father had given him totems and words of prayer to say when the spirits were against you. Robér repeated one of those prayers now, quietly. Claude chimed in on the last part. “We humble ourselves to you, great Kitchi Manitou. Drive out the mischievous Wendigo. We will only take what moose we need and leave in peace and respect. Amen.” Only Robér said the last word.

“You don’t say amen to Kitchi Manitou,” Claude said. “That’s reserved for Catholic spirits.”

Robér shrugged and peered around the forest. Nothing moved. The wind hung idle in the ambivalent forest. Thin beams of sun like yellowed prison bars pierced through the trees, mere artifices of illumination. Even with the wind idled dust swirled and danced through the spectral beams. Robér felt the hairs rise on his forearms and the back of his neck. He nudged Claude. “Should we go upstream and check there, ya reckon? Perhaps we can get a moose up there, and then we can go home. I know the moose there are kinda scrawny but maybe we can get two.” Claude only grunted. Robér continued. “My feet are wet and I’m going cross-eyed looking at the same damn trees. I’m sick of eating nuts that taste like gravel and jerky that tastes like beaver’s ass.” He slid the bolt back on his rifle; the shell jumped out and tumbled slowly and lazily into the leaf litter near his feet.

“You’re always fussin’ and bitchin’, Claude said. Keep that goddamned shell in that there rifle, aye. Moose will come, and if you’re clacking that there bolt when they do, they’ll run off,”

Robér retrieved the bullet, slid it into the chamber, and racked the bolt into place.

Claude was his best friend. They’d gone to school together, graduated together, and married two sisters, Mary and Shilu, within days of one another. They lived in the same log house where Robér had lost track of which of the seven kids running around were his and which were Claude’s, but he loved them all the same nonetheless. The sisters were twins, and Robér suspected that they switched beds on occasion for variety, and maybe mischief, without letting Claude or Robér in on it—or so the women thought.

With all those mouths to feed they needed plenty of food, and this was the time of year that the family expected moose meat. If they came home with no moose, Mary and Shilu wouldn’t yell at them, what they would do would be much worse: the tea would be weak, the supper bread hard, the bed cold, and the children whiney. Shilu would say to Claude, “Poor thing, let me help you with those boots, I know they’re so difficult for you in your condition.”

“What condition?” Claude would say. Shilu would pat his knee tenderly while giving him a pandering look of deep pity like she did with the old people who couldn’t put on their gloves anymore due to arthritis.

And Mary would say to Robér, “Be careful on the snow machine, don’t go too fast, those things are tricky to handle; I don’t want you to fall off and break an arm or drive into a gulley and get stuck.” That condescension, that treating them like one of the small children—implying that they no longer held the status of men—that’s what he couldn’t take, that’s what kept him in the quiet, unforgiving forest, freezing and enduring the pain of hunger, unending boredom, and the dangers of bear and Sasquatch. Even bears and the desperate cold could never put a stone in his gut, or stir unease, quite the way Mary could. When he disappointed her, she would gaze at him the way her people gazed in frustration and disappointment at an empty animal trap they’d just travelled twenty miles through deep snow to harvest.

Claude lowered his gaze from the forest in front of them and turned to Robér. “Something just ain’t right.”

“I know, the goddamned moose have gone off and disappeared. It’s been so long since I seen a moose, I’m beginning to think they all took a right turn and wandered over to Nova Scotia. If I saw one right now, I’d be so excited I’d piss my britches,” Robér said.

“No, you deaf man. Listen,” Claude said.

Robér heard nothing. Silence surrounded them. “Aye, no sounds. Not even skeeters buzzin’.”

“Bad energy here, the spirits are in a mood. I sense it. The moose sense it. I reckon we should move. Try up river a spell. Find a place with good energy,” Claude said.

“Ain’t that what I just said a bit ago anyway?”

“That you did, only you didn’t have a good reason for it, and I do.”

They abandoned their hide, packed their gear onto their Polaris snow machine, knocked the ice off the treads, and struck out on the trail. They travelled north toward the Fon Du Lac River, and after two miles, just within sight of the river, Robér spotted something large a ways off in a lonely, twisted tree. He eased back on the throttle, cut the engine, and motioned for Claude to look ahead. “I think we got a moose up a ways, under that tree. See if you can get a shot.”

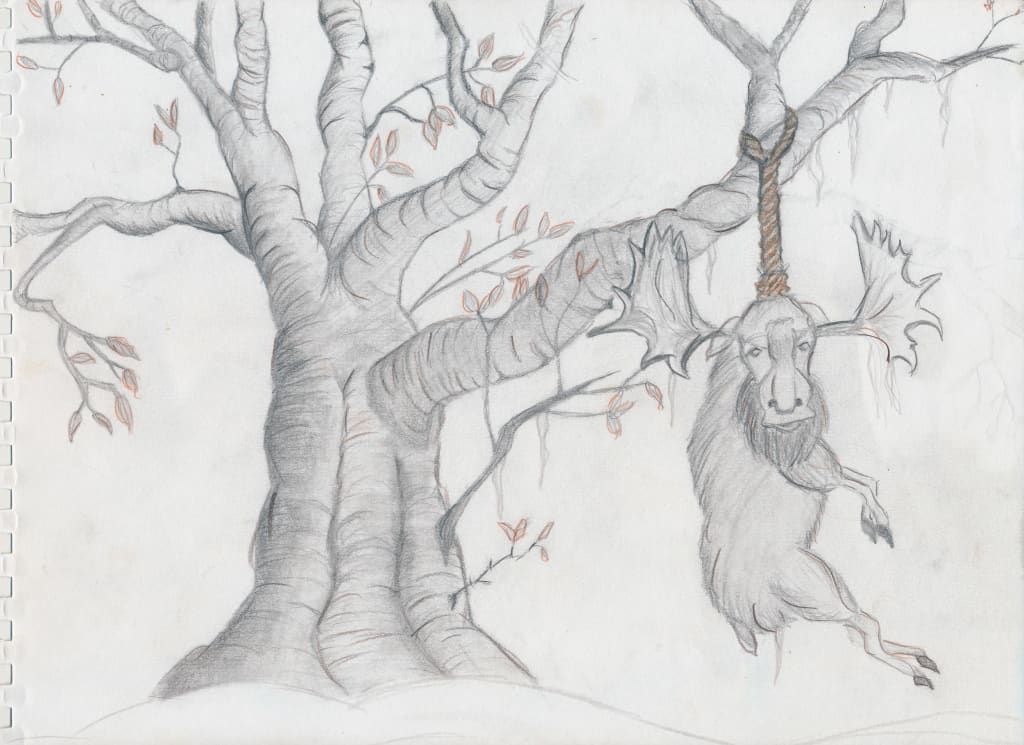

Claude, the better aim, shouldered his rifle and brought the suspected moose into his sights, but lowered the rifle without taking a shot. “No need to shoot that there moose,” Claude said. They disembarked and trudged up to the tree, post-holing their way through deep snowdrifts. They stopped in front of the moose and Robér regarded it swinging in the light breeze there, hanging from a thick tree branch by its neck in a hemp noose, its hind legs inches off the ground, its head canted to one side, its eyes wide open, one of which stared right at them.

“That there is one hung moose,” Claude said.

“How you reckon that there moose got strung up like that?” Robér asked.

“Well, that ain’t the work of other moose, that’s for sure,” Claude said.

“Yep, you’re sure right about that one. Moose are dumb. How many times’ve we tried to drag one of them big bastards outta the lake ‘cause they broke through the ice and couldn’t get back out?

“Plenty, that’s for sure, lotsa moose bones at the bottom of the Lac,” Claude said.

“You think he ran into that there noose purposely?” Robér asked.

“Well, I just don’t know, now do I?” Claude said.

“He’s got a right decent rack on him, I wonder how he got them there antlers through the loop? Robér said.

“I ain’t ‘xactly keen to the mind of moose and I don’t rightly care, ‘cause now I don’t have to sit on a frozen log for three more days waiting for one to show up. Kitchi Manitou heard us and has provided what we need,” Claude said.

“You’re thinking of taking this cockeyed moose? He looks weird, like he mighta did this to himself. Bad spirits have took holda him. It might not be safe to eat meat from a suicide moose,” Robér said.

“Whatever problems that there moose had, he ain’t got ‘em anymore.” Claude said, and jabbed a gloved finger into the moose’s ribs. “This here’s a gift from the spirits, not a curse, and bad spirits don’t possess dead meat, they stick around the living. Shilu and Mary will be happy. This is very good for us. I like my tea hot and strong.

“Yep, yep, I hear you, but I can’t get my mind offa how he got himself strung up there like that,” Robér said. “Maybe it’s a Sasquatch trap. Maybe he’ll be coming back and get really mad if we take his food. We don’t want an angry Sasquatch tracking us back home.”

“Listen, ain’t no Sasquatch hereabouts. Ain’t no Sasquatches anywhere if you ask me, and if there were, I don’t think they’d go around catching moose with a noose,” Claude said. “So we don’t have to worry about no one missing this moose. We’re takin’ it before someone comes along and sees it, and I’m damn glad we found him before he got rotted.”

Robér put his nose up to the moose to test his theory on the state of rot, but the cold had robbed him of his olfactory acuity. “Tell me this then, where’d that noose come from if not from a Sasquatch trap?” Robér asked.

“Maybe some dumbass kids put it up there as a joke. Maybe someone in Pete’s Village intended to string up a criminal without gettin’ mounties involved, and that big dumb moose just came right along, got curious, and got hung instead,” Claude said.

Something about this explanation didn’t sit right with Robér. This whole business had the markings of something inhuman. He decided not to steer the conversation that way; Claude would have plenty more to say on the subject, and he wanted to get moving before his fingers and toes froze. He stamped his feet to get the blood flowing and scrunched up his face to dislodge the icicles from his mustache, beard and nostrils. “Well, I ain’t exactly agreein’ with your explanation now, but you do make a good point about this here moose solving our problem. Now what we gotta worry on here is how’re we gonna get him back out of that there noose? That there rope is up where I can’t reach it, and I can’t climb with these here frozen fingers neither.”

Claude nodded in agreement as he studied the rope. “Yep, it’s gonna be somethin’ gettin’ him outta there. Gonna be somethin’ for sure. But we got another problem here—he ain’t been shot. Our women will see he ain’t been shot. They’ll think we went over to Pete’s Village and bought this here moose from Nanatuk’s meat locker, and that will be worse than if we didn’t bring home any moose at all. Shilu will hide my gun and say it’s ‘cause I might hurt myself with it.”

“Yep, we gotta get this moose lookin’ like he was hunted.” We gotta shoot this here moose postpartum,” Robér said.

“You mean postmortem,” Claude said.

“Whatever. Just make sure you shoot him where it won’t mess up the hide. I don’t wanna get grief from Mary about how she shoulda married a man who knew where to shoot a moose so it wouldn’t mess up a perfectly good hide.”

Claude fired a bullet into the head and then aimed a second shot at the neck, but Robér interrupted him. “Not so close now, that don’t look natural. Shoot him somewhere else, like a leg.”

Claude nodded in agreement with that logic and shot the moose in the upper part of the nearer back leg.

Once the moose had been properly shot they threw knives at the rope above the noose to cut the moose loose, but those bounced off and Robér lost his best hunting knife in deep snow for fifteen minutes before he found it and dug it out. After finding Robér’s knife they gave up on the idea of cutting the rope that way. Next, they both jumped onto the moose and held on to add weight to stress the rope, but all that did was get the moose swinging back and forth, making an eerie cracking sound in the tree. Nothing broke off except icicle missiles that flew down from higher up in the tree, stabbing at Robér and Claude. They jumped off the moose. Claude stepped back and fired a bullet through the rope the way Clint Eastwood shot through the noose around Tuco’s neck at the end of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. The rope snapped, and the moose dropped, sinking into the snow up to the base of its antlers. Robér and Claude dug it out and positioned the moose on the sled that was attached to the back of the Polaris. Robér reached for his coil of rope to tie down the moose but it had gone missing from the hook on the back of the sled. “Claude, you stow the rope somewhere else?”

Claude peered up from his work folding the moose’s legs to fit on the sled. “Nope, didn’t touch it.”

They cut up the noose rope instead into sections, using that and some other scrap rope to tie the moose down to the sled. When all was tethered tight and right they sped off down the trail.

An hour into the trip back home they met two other hunters coming up trail from the other direction. Both sets of hunters idled their engines. One of the other hunters pulled back his parka hood, removed a glove, pulled out a round container of Red Man, and placed a plug of tobacco in his cheek. Robér recognized him as Claude’s brother-in-law, Louis, and the other man turned out to be Louis’s cousin, Shorty. “Nice moose there, fellas,” Louis and Shorty said in unison.

“Yep,” Robér said.

Claude only nodded.

“More like that up trail?” Louis asked, pointing behind Robér and Claude.

“Huge herd up there in the forest, fellas. Just point and shoot, and get yourself a moose. You better hurry though, they was about ready to wander off,” Robér said.

“Aye?” Shorty said, getting excited.

“Aye,” Robér replied.

“I shot this one from a hundred yards out,” Claude said.

“A hundred yards? In the forest?” Louis asked and spat a glob of tobacco juice, making a brown hole in the white, virgin snow.

Claude saw the problem with his boast right away. In the span of a hundred yards there’d be a mess of trees in the way. “Well now, maybe it was fifty . . . yep, probably more like fifty. Hard to tell distance in all them there trees, you know.”

Louis and Shorty seemed to think that sounded plausible. They nodded, fired up their snow machines and went on their way with curt waves of their arms.

After Louis and Shorty had gone, Robér and Claude edited their story down to forty yards in order to head off any further questions along those lines. They practiced this new version of the details several times while sitting on their idling snow machine. When they were satisfied, they took off toward home.

The sun sank from view as they pulled up to their stout log house. It was covered on three sides by piled up earth, twenty cords of cut and split pine firewood, mixed with a smaller section of fir off to one side. A plume of smoke drifted up through the surrounding forest canopy from the large chimney in the middle of the shake and pitch roof.

The log house was spacious and cozy with one large main room that had a giant wood-burning stove in the middle. It had an equally large kitchen, a single bathroom and three bedrooms. It wasn’t insulated, but put together with giant fir logs, and caulked with a mixture of clay, straw and fiberglass that worked better than any regular house like they built in the cities. Hides, nets, guns, knives, saws and tools made of antler and bone hung on the walls in place of pictures, paintings and knick-knacks. The log house smelled of rubbed hide, cooked fat, smoke and pine. This log house was for living and for working on living.

They pulled the moose carcass inside and stopped to remove their outer clothing. Robér and Claude heaved the moose into the kitchen and up onto a giant butcher-block prep table, its legs sticking out into the kitchen area. Mary and Shilu kissed their men, then got to work, laying out decades old, heavily-patina’d skinning knives and cleavers that had been passed down from grandmothers and great grandmothers—each knife as sharp as the best Japanese Katana. Mary stoked the fire in the kitchen wood-stove to provide more heat to thaw the stiff moose.

All four stood around the moose exchanging small talk until the subject came around to their moose. Robér and Claude proudly relayed the story of shooting it in the forest. Mary asked, “Why’d you shoot it twice? Who missed the first shot?”

Robér didn’t like where this was going. “Now, Mary, it wasn’t like that, we had him dead on but he jumped at a bad moment so Claude had to shoot him again.”

“Did you now?” Shilu said as she squinted and inspected the two dry bullet holes. “Didn’t bleed much, now did he? You boys didn’t shoot him inside Nanatuk’s food locker now did ya?”

Robér and Claude fidgeted. Robér replied, “No, love, we came up on him by surprise under a big tree over near the Lac.”

Mary bent down and rubbed the moose hide and sniffed. “He smells a little advanced there fellas, and he’s frozen through; did it take you all the four days to drag him back?”

Robér and Claude shrugged and pretended ignorance.

Shilu said, “Well, you two go in the living room and sit down there by the warm stove. I’ll get you some tea while Mary starts on this here scrawny little moose. We’ll get you two fellas strong so you can go out tomorrow and get us a nice big moose.”

“Hey now, Shilu, this one here’s plenty big,” Claude said.

“He ain’t as big as the one Louis brought home to Erina last week, and we’re running low on walleye. So, unless you two want to go fishing and freezing all winter on the Athabasca ice, we’re gonna need another moose, or two if you keep bringing runts like this one.”

Erina was Mary and Shilu’s older sister, and she lived a half-mile down-trail with her two brats and her husband, Louis. Bragging rights between the sisters on which husband brought home the biggest and best moose was an honor of great importance. Shilu wanted a giant moose hide to spread out on poles in the yard for that uppity Erina to see as she went by on her snow machine each week. Erina had the largest moose hide in her yard this year. So big that Shilu snuck over six nights ago to make sure Erina hadn’t sown two hides together.

Robér and Claude threw more wood into the stove. They sat on low chairs nearby, soaking up the warmth. One of the older children came out and hugged them, said goodnight, and went back to bed.

Shilu brought both men cups of tea. “Now you two don’t get too close to the stove now, you might burn your poor toes.” She sauntered back into the kitchen and rejoined Mary in the moose dismemberment project.

Robér took a sip of tea and said in a low voice, while making a pinching motion with his hand over the cups, “Blechh, she musta just teased the water with the leaves rather than put any in.”

Robér and Claude drank the weak tea anyway. After they warmed up their limbs they put on their boots and went back outside. They stowed the snow machine, cleaned the sled, and set out the accumulated honey buckets for disposal. They came inside and sat back by the stove, where Mary and Shilu brought out their supper. Robér peered down at a walleye head and tail, a mound of clumpy, leftover rice, and a ragged piece of crusty bread that had two spots of mold on it. Claude sipped from a bowl of cold marrow soup that had a few lonely beans dispersed throughout. He grimaced. “I think I’ll sleep out here by the stove tonight where’s it’ll be warm.”

Robér finished his meal and glanced into the kitchen. Shilu and Mary stared back—two judges behind a moose carcass platform—their eyes interrogating Robér and Claude. Robér shivered even though it was almost too hot in the room. The women went back to butchering the partially thawed moose. They sliced skin away from fat and meat away from bone with deft speed and unerring accuracy. They knew every sinew and muscle in a moose. Robér studied Mary as she heaved a cleaver and cut through one of the moose’s knees, separating the tibia from the femur with a solid whack. Robér felt a sharp twinge in his left knee just then. He nudged Robér, nodding toward the women.

They both got up and wandered into the kitchen and stood beside their wives. Robér pointed down at the meat on the table. “Mary, I’m going to get you a moose twice as big as that one there.

Mary neatly parted two vertebrae with an authoritative chop, while grunting noncommittally.

Claude held up a corner of the hide the women had parted from the meat. “Aye, Shilu, don’t put this puny hide in the yard. Tomorrow we’re gonna get you a big moose. A moose so big you’ll have to stay up at night and keep watch over the hide so Erina don’t come to steal it.” They kissed their wives gingerly on their cheeks and went back to sit by the living room stove.

Robér and Claude drank the last of their tepid tea, reclined on thick, furry hides, and fell into slumber. Robér slept fitfully, bothered by vivid dreams of cleavers chopping through knees and backbones. He shook awake around 2 a.m. and rubbed his twitching leg. He peered around the empty and quiet room and fell back to sleep. He lapsed into a new dream of the vast snowy realm where moose roamed, evil spirits schemed, and men gathered together under deep black skies trying to live up to their names.

About the Creator

Karl Van Lear

I'm a screenwriter and story writer with a BA in Literature (creative writing concentation) from UCSC.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.