We’ll Talk Later

The weight of words left unspoken

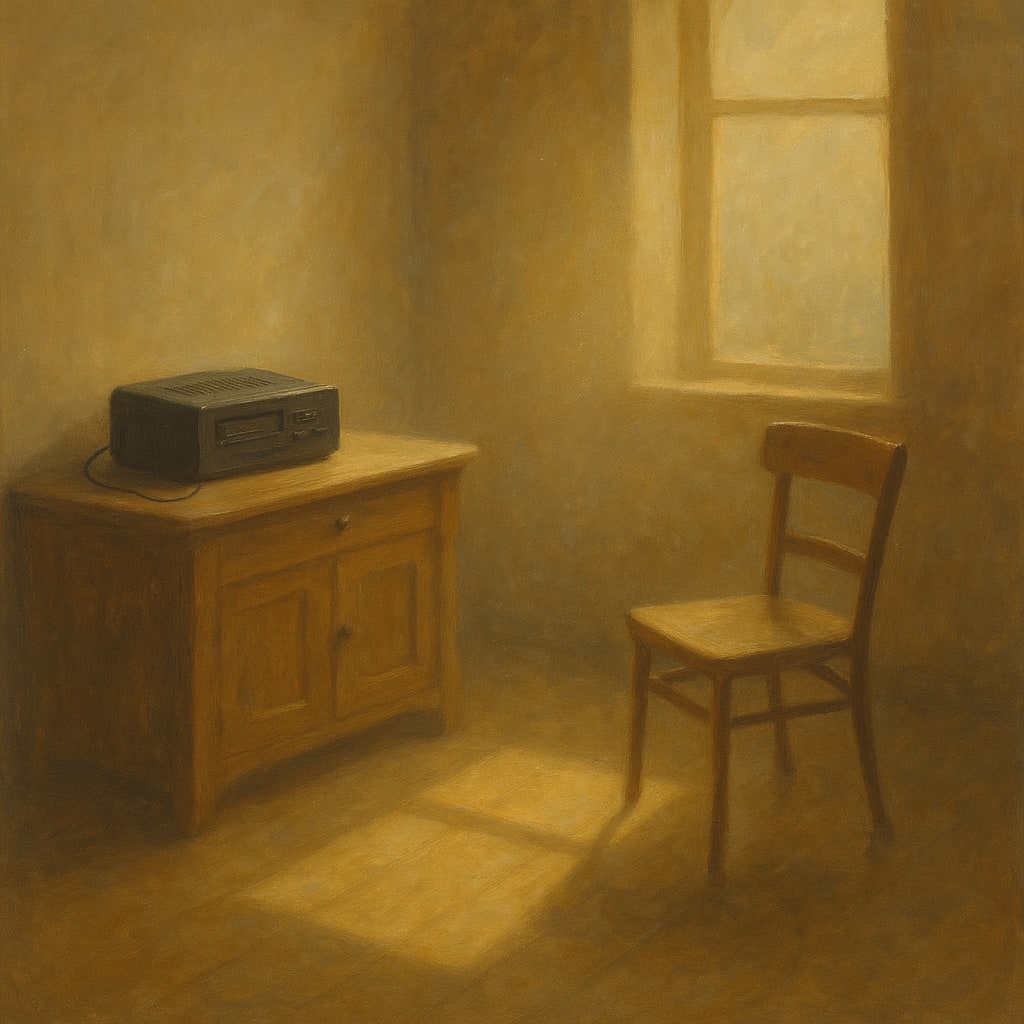

The answering machine still sits on the sideboard like a small black box with nothing left to say. The landline was cut years ago, but sometimes I still press PLAY and listen to the emptiness pour out, with that faint electric hiss of things that have ceased to exist without ever learning how to stay quiet. It’s there, in that hiss, that the conversation we never had begins.

You would have laughed at me for keeping the device. You always said objects don’t like being turned into mausoleums. "Either you use them or you give them away," you declared, a fighter when it came to matter. But the answering machine I can neither use nor give. It’s only good for fabricating a voice. Yours.

I don’t know when the conversation decided to grow inside my life. Maybe on the day of the funeral, when the basket of wild roses drew more eyes than your face. Maybe earlier, in the kitchen, when sunlight made golden rectangles on the floor and you said "later" without looking up from your saucepan, the way someone promises to close a window before nightfall. Later, we’ll talk. About the serious things. About what I am to you and what you are to me, outside all family mythologies. About how, both of us, we held life by the burning end. Later.

Later never came. So I tilted my ear toward another place in time.

At first, the imaginary conversation was made only of fragments: a "you know" suspended over the table, an "I should have" clicking like a lid screwed on crooked. Then it took the shape of a journey. I walked to work and you walked beside me for two blocks, just long enough for your phantom presence to bend my trajectory: I chose left instead of right because you liked brick facades, I lost five minutes at the cobbler’s window because you admired the patience of trades that repair. You didn’t order me. You opened doors in the air.

When at thirty I received the offer abroad, you were the first I lied to. Not in words — the conversation didn’t allow such blunt exchanges — but in silence. I pretended I didn’t need to ask you. Pretended we had already had that talk, the one where you would have said: Don’t mistake fidelity for immobility. Roots know how to travel. Instead, I packed my apartment while carefully avoiding imagining you perched on the suitcase, checking that every shirt protected its buttons.

On the station platform, I pulled out the old phone to dial a number that no longer existed. Your absence rang three times. At the fourth, the answering tone switched on inside my head, that familiar fizz of static. "Mom," I said without speaking, "I’m afraid of becoming someone you won’t recognize."

The reply came, as always, in that calm tone you used to announce rain: That is precisely the work of mothers: to learn how to recognize what has not yet grown a face. So I boarded the train.

Abroad, the conversation changed climate. It came in the mornings, when the light dragged pale aquarium colors through the curtains; it retreated at noon, as if the sun burned its tongue. It returned at night, obstinate, above the sink, when I gathered crumbs of unfinished days into a sponge.

You left me with tools and no plan," I sometimes accused.

Plans lie more than tools, you countered. Hammer first. You’ll understand later.

So I hammered. I hammered words into a language not my own until they consented to be inhabited. I hammered friendships into place with cups of coffee swallowed standing up, with confidences spilled too soon, too fast, like seeds thrown onto unknown soil. All this had a cost; I paid it at night by pressing PLAY to hear that hiss whisper: I hear you. Keep going.

That’s when I understood the not-conversation had weight. Not the weight of an order: the weight of a pendulum. It didn’t command me; it steadied me.

The year after, I met K. He laughed with the restraint of people who apologize for being happy. He listened in a way that made me believe my sentences. Quickly we inhabited the same space in turns: at his place, at mine, in the hallways of our schedules. He brought me lemons, showed me the patience a sauce requires, told me about a childhood on the edge of a city where the dogs knew how to open doors. I thought: finally, someone to speak to without you between us.

The conversation stepped back a little, politely, like a tide. It left me daylight. At night, it sometimes came back to lay small questions on the table. Do you want to be saved or to be met? Do you know the difference? I answered badly, then not at all. K. and I had found that delicate rhythm where two solitudes don’t cancel each other but light each other up.

Until the evening when K., his hand on the sink like on a ship’s rail, said: "I want a child. Not now. Not without you. But I want the desire, at least. Do you?"

I thought of you so hard I heard the click of the answering machine. Answer for yourself, your voice said. I surprised myself by saying: "I don’t know what I want. I only know what I no longer want: postponing what burns today." K. nodded, long, like someone listening to the sea decide what to do with the rocks. He kissed my forehead, and together we undid the possibility, without bitterness.

The not-conversation hadn’t chosen for me; it had simply held the lamp while I wrote my own answer.

Last winter, the conversation nearly went silent. A flu badly handled, a hospital too white, nurses practiced in the art of speaking low. I found myself in a hallway bed, without my objects, without your answering machine, without anything that knew how to make sense out of machine hum. I thought I had lost you a second time.

Fear cleans a room that way. It leaves only a corner of table, a chair, a glass of water. I laid my forehead there. "I don’t want to die without having truly spoken to you," I thought, as naïvely as when at seven I hid in the wardrobe to cry more comfortably. Silence swelled to cathedral size.

Then, against expectation, the conversation slipped in somewhere else: not ear, not memory, but skin. A warmth settled in my palm, distinct, stubborn, like someone had left a coin long held there. We’ve been talking for years, you said without voice, and you think it’s not talking because no one can transcribe it. I cried noiselessly. A nurse handed me a tissue with the authority of those who know exactly the value of tissues. I slept.

I left the hospital with the very clear sense that the conversation wasn’t a ritual of consolation, even less a superstition. It was a practice — like reading, cooking, walking. Something to be learned, worked, refined. I was no longer afraid of resuming it, the way one resumes the piano after months away, hesitant at first, then finding the melody again.

In spring, I sorted your house. Boxes full of honest things remained: stiff-clean dishcloths, orphan glasses, spools of thread that smelled of childhood. In the sideboard drawer I found an audio cassette. No title. Just your small handwriting on the label: For later. My heart, that docile old muscle, made the stupid sound of a stone dropped in a bucket. I rushed to the friend who still owns what’s needed to play such relics. We blew the dust off like sweeping a threshold before entering someone’s house.

The tape crackled a while; you could hear dishes, a window, maybe the radio. Then your voice — but not as I invent it: slower, fuller, with hesitations I had forgotten. You were clearly testing the device: "One, two… does this work? Good." Then, with a little laugh: "For you, for when it’s needed."

You didn’t say my name. You didn’t reveal secrets. You spoke of the best way to remove a cherry stain, the virtues of writing shopping lists with marker, how a lemon can save a sauce gone sad. "And when you hurt," you added, "set water to boil. You don’t heal, but hot water gives the world the idea of leaving you alone a while."

I expected a testament; I received a manual of attention. It was more just. You found a way to be useful to reality. And it was, very nearly, the conversation we never had: not a settling of accounts, not even a declaration — just a pedagogy of the everyday that says "I love you" without consuming the words.

The cassette ended with a breath, then a rustle: We’ll talk later, you whispered, as if you were setting the phrase on the table along with the salt. Irony, if it exists up there, must have smiled.

I went home with the player, the cassette, and the desire never again to postpone what I can hold. That night, I laid on the answering machine a piece of paper with four sentences I no longer wanted to leave in the cloud: I forgive you. I continue. I am still learning. You can rest now.

I don’t know to whom they were addressed; to you, to me, to the world in general. The next morning, the paper had absorbed a trace of humidity — as if it had sweated from having kept watch. It made me laugh. I fixed myself hot lemon water. The world obeyed: it left me a little in peace.

Since then, the conversation has changed status. It’s no longer only the thread strung between us; it has become a way of living with what does not yet or no longer exists. I speak that way to what I hope for, to what I fear, to what I don’t understand. Sometimes I answer the future as if replying to a letter delivered early. Sometimes I write to versions of myself I will not inhabit. They answer with the politeness of ancestors.

You didn’t leave. You just moved around the house. You’re in the saucepan of water beginning to tremble, in the faint dust-smell when a new bulb accepts current, in the strip of tape that refuses to peel straight. You’re in the refusal to confuse importance with noise. You’re in the way I look at people who talk too loudly: with tenderness for the solitude that drives them.

I still sometimes press PLAY and listen to the nothing organized by the machine. I even sometimes leave messages for you there, speaking aloud, just to test the timbre of my truth. The answering machine swallows everything, without judgment. I sometimes imagine a post office that would receive such mail: Center for the Sorting of Unspoken Conversations. I’d send whole parcels there.

The last time I played the tape, I was surprised not to wait for your voice. The hiss was enough. I understood that the conversation we never had had already worked: it had taught me the art of listening to what has no words, of welcoming what weighs without being seen, of choosing without witness.

This morning I turned the chair toward the window. The light drew a long shape on the floor, an almost-rectangle nibbling slightly at the baseboard. In that geometry, I recognized — perhaps invented — the silhouette of what is missing. I made room for it. I laid my hand on the backrest, and without pressing any button, I said: "I hear you."

The kettle began to sing. The water understood. The world, for a few minutes, held still. And the conversation, as always, found its sequel in the gestures.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.