UKIYO

An inundated Japanese passenger through space reflects on his dystopian past, present, and future.

“Life is good with less teeth,”

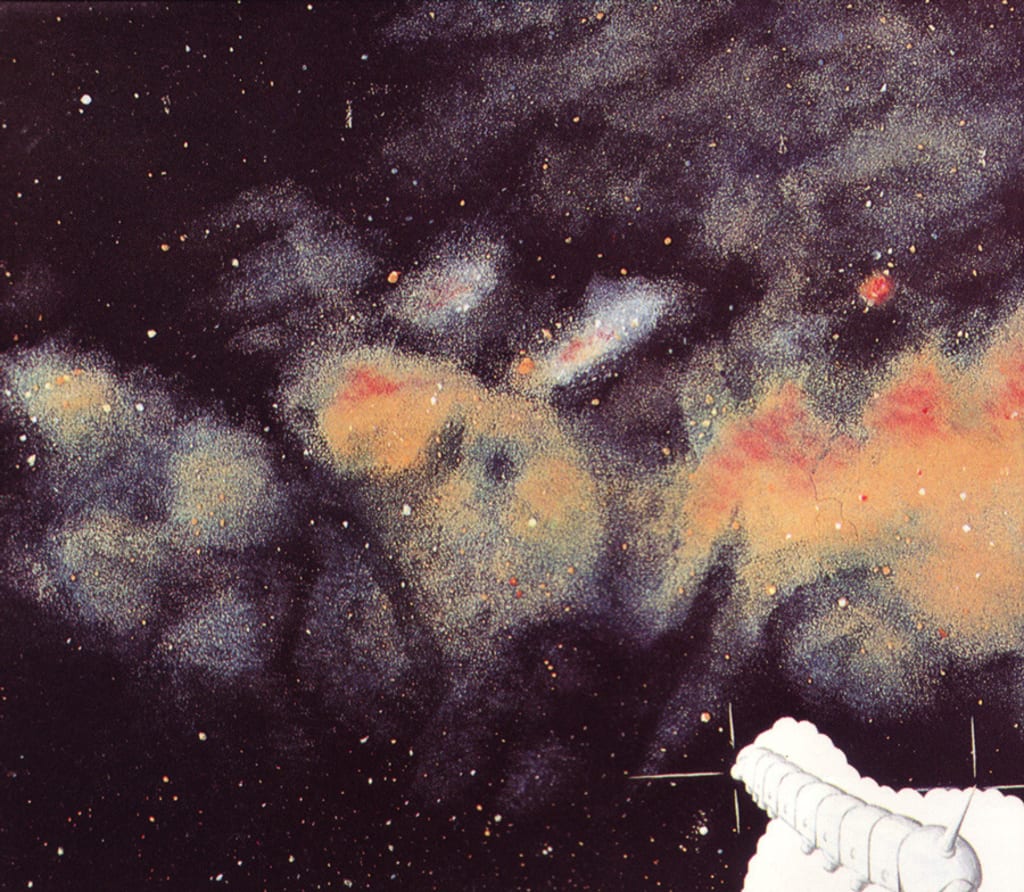

Koro thought, as the taste of freeze-dried cherries settled into his naked body. In front of him, the stars shone in the cold lacquer sky. Lapping peacefully, the amniotic fluid sent pleasurable waves over his pale, hairless skin. His teeth, black like burnt bodies, worked lazily, mixing his saliva with the fruit, as if by squeezing out the moisture from his own body, he was imagining juice.

Let me tell you a story: A woman visits a great temple and falls in love with a young man. Captivated, she orders a furisode with the same pattern as his robes. She wears it until it kills her. The furisode is sold. Used again. Death. Used again. Death. A priest has the bright idea to try to burn it. The gown, set ablaze, dances away into the city. And the fire burns Edo, killing 100,000 people.

Would you believe me if I told you that this story is hundreds of years old? From an age where the rich also paid for living dead (too much politics if you were to really die), of demons and deities, love between men, and beautiful art. Sometimes, in the monotony of his sleek space pod, Koro liked to remember the women from the story who died wrapped in their own obsession: how they all saw the same man. He was beautiful, they say. Beautiful to believe in. Beautiful as their sins accumulated. Beautiful as they scorched the earth.

In the drug-induced stupor of the chemicals that seeped through his skin, Koro had come to master the art of sleeping. This, of course, was something he had already learned as a college student in Tokyo, but in space, who really cared? It was heaven, really, floating from consciousness to unconsciousness in a lucid state of nostalgia, looking up into the vast deep. Sleep for a little bit, wake up, sleep again.

He would dream, and wake up years later, in the pale pink fluid, with no sense of real panic at the distance from his home, no anxiety about his place in the stars. Back on Earth, other people had only recently decided to be drugged out all the time. For the rest like Koro, bliss was always followed by betrayal, a night of beer and sake followed by a roaring hangover, a tear-filled spring graduation followed by a starved, over-populated job market, a beloved, overripe family member followed by bittersweet heartbreak. What a stupid way to live.

Suddenly, Koro had the sensation that his skin was growing whiter, white like the moon-men, white like the rabbit, white like wrinkled toes in ocean foam. He was by no means the worst of the eta, the leather people, who had been hit hardest in the wake of the Second Wave sickness, when Koro was still young. As your teeth blackened, your skin whitened. You vomited blood, became feeble, lost your hair, wilted like flowers and willows. Babies emerged with still little doll faces.

Remembering this, Koro’s eyes squinted a bit in the starlight, and he licked his lips, red with the idea of juice. Had he seen that constellation when he went to sleep? Was he dreaming, or dying? What was the name of that girl at the Shostakovich concert? What were the old men doing when medical supplies ran low? Why did we kill ourselves? In response to his rising heartbeat, the system released another wave of sedatives and opioids, immediately knocking him back into stasis. He had a long journey ahead, probably. Smiling, Koro contemplated that it felt like the kind of sleep you get after orgasming very hard.

He let the dream wash over him, like the ocean sweeping away human footprints in the sand.

In the garden, Koro’s grandfather is pulling up plants, leafy and heavy with solar radiation. “Mabiki.” Pulling out plants in an overcrowded garden. The waves of sunlight overlap with the drone of cicadas, and the distant barking of a dog. Sweat drips down his face, into his face mask. He coughs, smiles, touches the heart-shaped locket around his neck.

Did you know, that the Edicts on Compassion for Living Things forbade the killing of dogs, how they flooded Edo, shat on everything, reminded Japan of the horror of exponential growth? What a sight it must have been. “Daimyo Tsunayoshi’s multiplying dogs are shitting on everything”, whispers a samurai retainer. “This city stinks,” moans a nightsoil shoveler. How the past repeats itself.

Maybe it was that reminder that eased the pain of mabiki, of returning the newly born to the earth, that was so widely practiced in the Edo period. Children, born, die. Born again. Death. Born again. Death. Babies were not considered people yet. In the streets, geisha with black teeth, lead poisoning from white face paint, and the intentional mercury poisoning in the first-day-of-the-month-pills. But it would have been a waste for Koro’s grandfather to lay waste to Koro in the 21st century, there were only so many children, and only so much time. There were cherry trees to graft, preparations to be made. Watching from the shade of their summer home, Koro traced the smooth wood porch running around the house, scratched his ass, looked at the scorched clouds nearing the garden. He hoped this was one of the good memories, and not one of the dreams.

If only we might fall like sour cherry fruits in the summer — so rotten and radiant!

A few years later, Koro is awake again. Is his destination close? The stars outside the shuttle seem to have gotten farther. No mind, he thinks. But despite the boundaries of his hermetically sealed chemical paradise, something occurs to him.

Let me tell you a shorter story.

“The Edo people had more remaining teeth than modern-day society. This finding was unexpected. The notion that ‘people of long-past ages lost more teeth more quickly’ does not seem to apply to people in the Edo period in Japan.”

Life was good, Koro thought, even when we had less teeth. Before we sent the kids into space. Even when our teeth got black from telling lies and smoking regrets, when we got sweet cavities from festering hope, and replaced them with gold fillings. When inoculation was still a political threat. When there were other people. When it hurt to be alive.

With all the strength in his gummy, black teeth, and white, naked body, Koro grins so hard that tears roll down his face into the nutrient bath, his eyes brimming with stars.

"I miss you, ojii-chan."

About the Creator

Sebastian Yong-Ah Chang

Sebastian Chang is a Korean-Indian artist and Yale student figuring out how to be happy. He enjoys penning strange poetry, studying Japan, and writing music. He likes his girlfriend and is scared of the dark.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.