The Woodpecker in the Spare Room

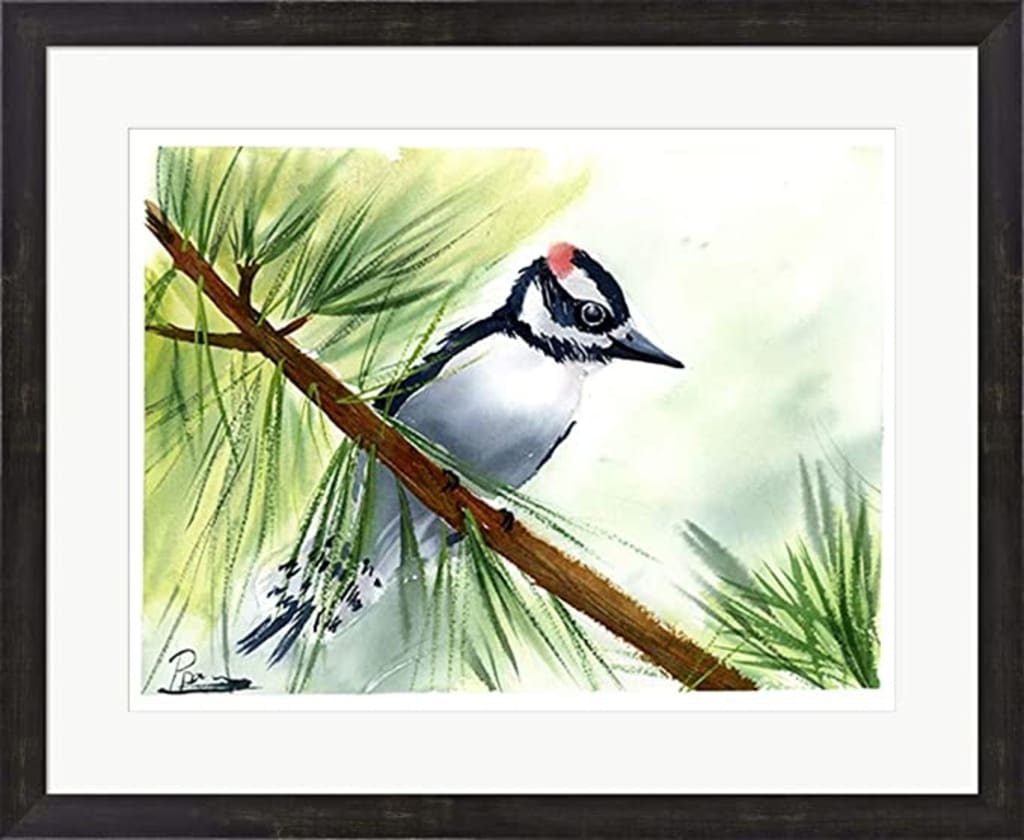

"In composition, form and selection of colour it was equal to anything in the National Gallery in Sofia, and Markova’s unique style gave it an irresistible zest all of its own."

[I]

On the 30th July, 2003, the artistic world suffered a great loss.

For on the 30th July, 2003, Violeta Markova, arguably the greatest artistic talent to come out of Eastern Europe since Mihály Munkácsy was taken from us.

Why is it that many of the greatest artists seem to die so tragically and so young? Look at van Gough. Pollock was not that old either. Markova was but twenty-nine, mown down by a careless motorist on his way to Gabrovo. Her life was just beginning. She had so much left to give us. Why?

Yes indeed, Gospozhitsa Violeta Evgenina Markova was the greatest artistic talent of our generation; Bulgaria’s finest flower. And she knew it. When people came up to her and asked, ‘Miss, what is it that you do?’ she would proudly reply, “I am a painter, I am an artist.” And she was. The very, very best.

The question begs therefore, as to why have you not heard of her before now? Please, let me explain.

I suppose the tale of Violeta Markova really starts when she was born into this world on the 15th March, 1974 at the city hospital in Pleven. Yes, I should start there but I will not. After all babies are babies, much alike to one another except in the eyes of their mothers of course. Before the age of two or three Picasso, Beethoven, Stalin, your Mathematics teacher at school, the lady who sells tickets on the bus, the postman and Jesus Christ were all much the same. Well, perhaps not the latter, what with all the angels, childhood miracles and so on, but for us mere mortals, yes, we are all far too similar; crying, smiling, drinking milk and filling nappies.

But around the age of three we change and our characters emerge. And this is where the tale of Violeta Markova truly begins, for it was at that age that her mother, Tsveta, began to notice that her young daughter liked to draw with the felt tip pens and chunky crayons that lay around the Markovi apartment. Not that her etchings were any good mind. They were like the creations of all toddlers really, masses of multi-coloured scribble, but Tsveta was proud of her offspring and so she took some of the better ones and taped them to the front of the big white refrigerator that stood in her kitchen.

By the time that Violeta had reached the age of five though, the drawings had begun to bear some resemblence to what they were purported to be. When Violeta told her father, ‘Tatko, this is you,’ Evgeny Markov could make out his facial features, fair hair and flat feet on the picture and even more miraculously, when she showed him her interpretation of Baba Rada’s house, he could clearly make out the two-bedroomed village dwelling with its fig trees, vines and Sasho the pig who lived in a sty at the back.

“I do think that our Violetka’s got a real talent for drawing,” he remarked to Tsveta.

“I know Gencho, and she’s at it all day long,” replied his wife. “She’s not at all interested in dolls like most little girls.”

It was not long before others started to notice too, as the etchings got better and better, until by the time that she had started school her creations were of a quality surpassing that, (I am sorry to say), of many adults.

“Oh, she’s marvellous with art,” gushed her class teacher, Mrs. Popova, at a meeting with Violeta’s parents, showing a recent portrayal of Father Frost as evidence. “However,” she continued, “we do have a few problems with some of the other subjects…”

And alas, she was right. For Violeta Markova was so wrapped up in her art it seemed, that biology, mathematics, history, Marxist theory, Russian and the whole multitude of other tedious things that are taught to children at school all appeared to have fallen by the wayside.

And with them fell her behaviour, and I am again sorry to say that the Violeta Markova who was preparing to leave school in 1992 was a young lady with a woeful school report, an indignant attitude and, (high grades in Art excepted), an abject lack of academic qualifications.

“And what do you think you are going to do now, young lady?” asked her father when he sat her down to talk about the future.

“Paint,” replied his oh-so-ambitious offspring.

“Paint?” he repeated, before adding, “And how will that keep you in food and water exactly?”

“Dunno.”

“If you’d managed to pick up a few other qualifications instead of messing around so much, then you might have been able to get a scholarship for university but nobody wants a student with but one decent certificate unless they are prepared to pay and we haven’t got the money…”

“I know, I know! Besides, I wouldn’t want your money even if you had any, don’t worry, I’ll make my own!”

“And how will you make your own exactly, Gospozhitsa?”

“I’ve told you already. I’ll paint!”

And so she did, for that day Violeta Markova went into town and spent the last of her money on a proper easel, some oil paints and several canvases, and then the very next day she headed off on a grumbling old bus to some woods in the countryside to paint birds, bees and butterflies, (for by now our heroine had specialized and the joys of nature were her domain). And after two weeks or so of daily and lengthy trips to the forest, she returned with the fruits of her labour, a magnificent rendering of a woodpecker sat in a tree. In composition, form and selection of colour it was equal to anything in the National Gallery in Sofia, and Markova’s unique style gave it an irresistible zest all of its own.

“It’s beautiful!” declared Tsveta.

“Remarkable,” added Evgeny, “but can you sell it?”

“Sell it?” puzzled the artist.

“Violetka, great as your talent undoubtedly is, I can’t afford to go on keeping you in sustenance. Now you said that you wished to earn a living by painting, right? Well my girl, to do that, you’ve got to be able to sell the masterpieces that you create.”

“Don’t worry, Tatko, I’ll sell it.”

But alas, saying something and doing it are two completely different things entirely. Not that Violeta did not try hard of course. Why, she tried very hard indeed, approaching every rich or artistic soul from here to Mezdra, but nobody seemed to want that fair woodpecker. Not that they didn’t like it either. Quite the opposite in fact, for everyone was captivated by its beauty and it received more words of praise than old Dimitrov himself had in his heyday. No, the problem was that which blights all life it seems. ‘I’d love to buy it, Gospozhitsa, but business is bad at the moment. There’s no money for frivolities like art you know?’ Did she know? Of course she knew. Money, money, money. Always no money. Her family had no money, she had no money, no one in Pleven had any money, no one in the whole damn country had money. Her father chastised her and ordered her to get a ‘proper’ job, ‘one that pays’. She stormed out of the room, slammed the door and burst into tears in her bedroom. But it was not his fault, and she knew it. Several hours later she re-emerged and began to search for a job.

But jobs, even for talented young artists are seldom to be found, particularly in towns like Pleven where the factories lie dormant, machinery rusts, businesses struggle, and despondency prevails. It is perhaps hardly surprising that two weeks, no job and an unsold picture later we find our female Fedotov sat on a train accompanied by a large suitcase. Her destination is her Aunt Kristina’s apartment in Sofia and her hope, to do in that big city, the capital, what she could not do in her hometown. Make some money.

It appears that the Gods were kind to our Painter from the Provinces. Tyche smiled upon Violeta Markova and provided her with employment as a waitress in a restaurant that was noted locally for its chicken soup and bean salads, whilst Aphrodite showered her blessings upon the lass in the form of Mitko, a gangly gallant from Gabrovo who earned a living mending motor cars. Yes indeed, life had improved and indeed Violeta’s only complaint could be that after a hard day dishing out salads and steaks, and with a boyfriend who appreciated Slavi [1] more than Cezanne, she was normally far too tired and busy to exercise the gifts that Helios had bestowed upon her. Occasionally, in the park or on a trip to the mountains, she did manage a hasty yet exquisite sketch or two, but alas those occasions were all too few and two years after her arrival in the big city her portfolio was still far from bulging.

But bounteous though the blessings that she received were, it seems that some people are hard to satisfy and the powers that be must have been somewhat irked when they heard Violeta conversing with her friend and colleague Lora, one Thursday evening some three years after her entry into Sofia.

“He’s intolerable,” she moaned. “Every night I get in and he’s sat there watching TV. No cooking, that’s my job of course, no just glued to the TV.”

“I’ve told you before Viki,” empathized the waitress, “you’re too good for him. I wouldn’t put up with the whole phoning you all the time as well. He’s your boyfriend, not your prison warden.” Lora Getsova had long been a critic of the possessive mechanic who chose that moment to call the love of his life’s mobile phone as if to prove the point.

“But what would I do if I left him? I’d feel bad about going back to my aunt’s, but the money that I get here is hardly enough to pay for food, let alone to rent an apartment with. And all my friends here are his friends. Well, apart from you that is…”

“Viki, listen! If you’re really serious about leaving Mitko, I’ve got an idea…”

Lora Getsova’s idea involved a brother who was living in London, and who could get them work there with wages more akin to two thousand deutschmarks a month than two hundred. It would be difficult, particularly getting visas and such other bureaucratic hurdles but wouldn’t it be worth it? Two close friends sharing an apartment together in one of the world’s most exciting cities AND earning enough to be secure for life.

“Oh, with all that money, lots of fresh inspiration and no interference from Mitko, I’ll be able to buy canvasses and paints and resume my painting,” sighed our heroine, in a dream world of Marble Arch, Monet, money and minus mechanics.

It was some time later however, before that dream could become reality and our Bulgarian Braumann landed in the British capital. The delay is of little interest to us; a frustrating series of fiscal and legal headaches and a tangle of red tape interspersed by unnecessary periods of waiting around and twiddling thumbs. They concern us not, and so I won’t go further into them except to say that they did nothing for Violeta Markova’s artistic side whatsoever, and instead we shall take a holiday from this tale to concentrate on those everyday issues of life such as work, cooking, balancing bills and vacuuming the house which tedious and boring though they might be, are alas of more immediate importance than painting or reading short stories. But when those tasks are completed, let us rejoin each other several years later in Part Two where she will continue the tale of Violeta Markova.

[II]

The weather is warm and bright, but the sodden tarmac testifies to a bout of rainfall which fell upon this tiny section of the Earth’s dimpled surface but an hour or two ago. It was heavy but short-lived and the meteorologists amongst us would have immediately recognized it as being of a convectional nature, which to us laymen, means that it was caused by a vast amount of water, evaporated in the intense summer heat, accumulated in the air and then falling to the ground when it got too heavy. Our heroine, the artistic hope of the Balkans, the gifted Violeta Markova, stes foot on that damp surface after alighting from the steps and makes her way over to the waiting bus. She breathes in the still fresh air and thinks to herself, ‘Ah, it is good to be home!’

Home! Yes, home! For the first time in how long? Why, it must be six years. Well, five years, nine months and three days to be exact. Yes indeed, Violeta is back in Bulgaria. Back after her lengthy sojurn overseas. Back after over five years of unqualified success.

For all had gone well.

The job with Sasho Getsov HAD materialised. It had not been the greatest job in the world, merely waiting on in a restaurant owned by his friend Petur Aleksandrov, but at seven pounds an hour, ten hours a day, for five days of the week she’d been able to put quite a bit aside AND have time for a weekend part-time job on top.

And working all the time had meant that her spending had more or less been limited to food and accommodation.

And sharing a room and meals with Lora and then later her new and less possessive boyfriend Vlado, meant that even these costs were kept to a minimum.

And three months ago, there was the icing on the cake. Her Britannic Majesty’s government had decided to grant her a three-year business visa! She was lucky, loaded and long-term legal. As I said, an unqualified success.

Unqualified? Really Violeta?

‘Well… ok, so I haven’t been able to move my painting forward that much. You know, what with working so much and…’

How much painting or even sketching have you done this last six years Ms. Markova?

‘Well… not much, erm, well… actually…’

None?

‘Well, erm… yes, erm… none. But that’s not the point is it? After all, money to live on is more important isn’t it? And I wasn’t going to miss this opportunity to make that sort of money was I? It would just be stupid wouldn’t it? I mean, you can’t eat paintings can you? Nor are they a pension for old age. Besides, now I’m all ok regarding visas and such, I’ll devote a little more time to my art. Yes, you’re right, it would be a shame to let it go to waste wouldn’t it? Indeed, that’s a resolution! As soon as I return to London I’ll get out the sketchbook and get my art going again. Life’s not just about work and money you know!’

Did she mean it? Who knows? Young Violeta is not a dishonest girl, but there again, she HAS made similar such declarations in the past, but well life and all its trivialities and demands seemed to get in the way. But the circumstances are different now aren’t they? Aren’t they..?

Alas we’ll never know. For as I said previously, on the 30th July, 2003, Violeta Markova was taken from us. She was just twenty-nine, mown down by a careless motorist on his way to Gabrovo. Her life was just beginning. She had so much left to give us. She was crossing the road at the time and had looked the wrong way. She was used to traffic coming from the right, not the left.

The 30th July, 2003 was indeed a tragic day for mankind. For at 09:25 Paolo de Silva, the great Brazilian mathematician was killed when a mudslide washed him and his favella home away. He’d done well in the school run by the nuns, but there was more money to be made in stealing mobile phones than in mathematics. And at 11:41 Nguyen Thi Tu Anh, the world-class Vietnamese cellist succumbed to cancer. She always loved to play but had never had time after working in her mother’s noodle restaurant. And then at 16:43 Fatima Umm-Hussein, the canny Saudi Arabian stockbroker died of a heart attack. If only her father and husband had let her pursue a career after leaving university.

And at 17:43 Bulgaria’s greatest ever artist, the talented, imaginative, hard-working and creative Violeta Markova died in a road accident leaving us no evidence of her exceptional gifts other than an early study of a woodpecker sat in a tree that hangs in the spare room of the apartment of Gencho and Tsveta Markovi.

London and Kuala Lumpur, July – August, 2003

Copyright © 2003, Matthew E. Pointon

[1] Slavi – Slavi Trifonov, a popular presenter of a variety show on Bulgarian TV. Symbolises Bulgarian low culture

About the Creator

Matt Pointon

Forty-something traveller, trade unionist, former teacher and creative writer. Most of what I pen is either fiction or travelogues. My favourite themes are brief encounters with strangers and understanding the Divine.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.