Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Tell-Tale Heart, first published in 1843, is a chilling tale of madness, guilt, and the unreliability of the human mind. The narrative is delivered in the first person, from the point of view of an unnamed man who insists, from the very beginning, that he is not insane. This constant denial of madness, however, only underscores the depth of his instability. He claims that his heightened nervousness has sharpened his senses, particularly his hearing, to extraordinary levels. Far from being ruined by illness or madness, he believes his mind and body are stronger than ever.

The narrator admits that an idea had taken root in his mind, an idea that he could not shake and that eventually consumed him entirely: the murder of the old man with whom he lived. He confesses that the old man had never wronged him, never insulted him, and had even been loved by him. It was not money, greed, or revenge that motivated the thought of murder. Instead, the source of his obsession was the old man’s eye. One of the man’s eyes, pale blue and filmed over with a strange haze, resembled to the narrator the eye of a vulture. Whenever the narrator looked upon it, his blood ran cold, and his very soul was filled with dread. He became convinced that the eye was evil, and the only way to rid himself of its influence was to destroy the man who bore it.

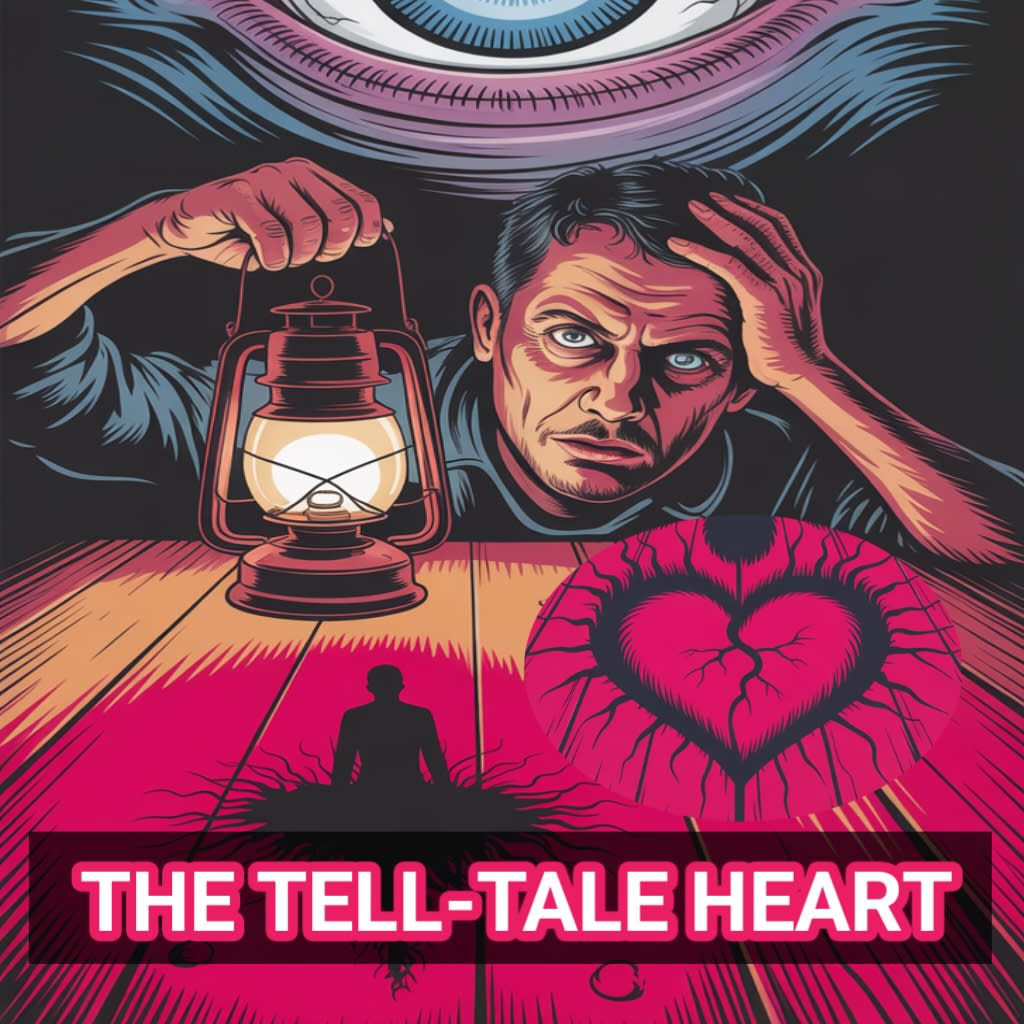

In the days leading up to the crime, the narrator behaved with unusual kindness toward the old man. He claims never to have been more considerate or affectionate than in that final week. This was part of his cunning design. Each night, just at midnight, he crept to the old man’s chamber. With a patience he praises as proof of his sanity, he would spend an entire hour opening the door just wide enough to slip his head inside. In his hand he carried a lantern, its shutters closed so that no light escaped until he wished it. With the slowest precision, he would inch the lantern open to direct its narrow ray upon the dreaded eye. For seven nights, he repeated this ritual. Each time, however, the eye remained closed, and though he felt the beating of his own tense heart, he could not bring himself to strike. Without the eye to haunt him, he reasoned, there was no need to kill.

On the eighth night, fate intervened. As the narrator slipped his head into the chamber, his thumb brushed the latch of the lantern and made a sudden noise. Startled awake, the old man sat upright in bed and cried out in fear. The narrator, hidden in the darkness, stood perfectly still, saying nothing, breathing scarcely at all. For a full hour he waited, hearing the old man’s terrified heart pounding in the silence. He knew that groan, he tells us—the groan of mortal terror that rises from the soul when one knows death is near. At last, he dared to open the lantern a crack, and the dim ray fell directly upon the open vulture eye. Its hateful gaze filled him with fury.

Now, along with his own pounding heart, he heard a sound “like a watch enveloped in cotton.” To him, it was the beating of the old man’s heart—fast, terrified, thunderous in the night. Convinced that a neighbor might hear, the narrator’s calm gave way to sudden violence. With a cry, he leapt into the room, dragged the old man to the floor, and pulled the heavy bedclothes tightly over him until no breath remained. The eye would trouble him no more.

Even in recounting this, the narrator boasts of his cleverness. He had planned so wisely that not a drop of blood escaped. Using a tub, he caught every trace. He then dismembered the body and concealed the pieces beneath the wooden floorboards of the chamber. With careful precision, he replaced the planks so skillfully that no human eye could detect a thing. His triumph was complete—he was certain of his own genius.

But as he basked in his success, a knock came at the door. Three police officers entered, explaining that a neighbor had reported a shriek during the night. The narrator smiled. His composure was flawless. He welcomed them in, explaining that the sound had been his own, a cry from a dream. He led them confidently through the house, even to the old man’s chamber. In his arrogance, he placed his chair directly above the hidden corpse, and sat there talking easily with the officers.

At first, all was well. The policemen seemed satisfied. But soon the narrator’s heightened senses betrayed him. He began to hear a low ringing in his ears, faint at first but growing steadily louder. He tried to talk cheerfully, to mask his unease, but the sound grew more insistent. It became a steady, rhythmic thumping—like the beating of a heart. He gasped and shifted in his chair, scraping it across the floorboards. Still the noise rose, until it roared in his ears.

Convinced that the officers must also hear it, he believed they were mocking him by pretending not to notice. His terror mounted to agony. The sound, he thought, was the old man’s heart, still beating beneath the floor, demanding justice. Unable to bear it another moment, the narrator shrieked a confession. He begged the men to tear up the planks and end the horrible sound. With his own words, he revealed the murder, betrayed not by the evidence of the crime but by the torment of his guilty conscience.

In this terrifying tale, Poe explores how guilt can drive a person to madness. The narrator’s insistence on sanity only highlights his descent into lunacy, and the “tell-tale” sound of the heart symbolizes the inescapable power of conscience—a power that no cleverness, concealment, or denial can silence.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.