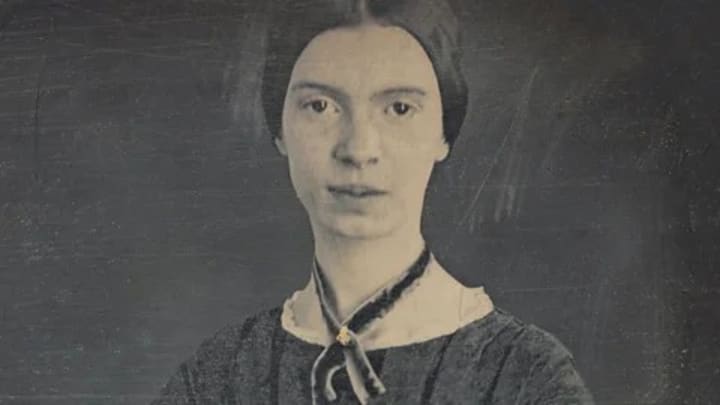

The Solitude of Emily Dickinson

The poet who lived upstairs, and the world she never left

In the upstairs bedroom of a large white house in Amherst, Massachusetts, Emily Dickinson lived most of her adult life, unseen by many and misunderstood by nearly all. She was not a ghost, though some neighbors suspected she might be one. She was not a saint, though her letters held a kind of quiet gospel. She was not crazy, as some whispered after she stopped attending church or appearing at town functions. She was simply herself—fiercely private, deeply observant, and impossible to categorize.

Born in 1830, Emily grew up in a household that respected books, order, and appearances. Her father, Edward Dickinson, was a stern lawyer and a trustee at Amherst College. He believed in education, discipline, and God—in that order. Emily learned Latin and studied science; she read Shakespeare and Emerson. She loved flowers with a precision usually reserved for astronomers or taxonomists. There was nothing casual about her affections. When she loved, she loved entirely, whether it was a person, a book, or a crocus breaking through the frozen earth.

As a young woman, she was social in the way young women were expected to be. She wore white dresses not yet become legend, she went to Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, and she danced, occasionally, when the occasion called for it. But something inside her shifted in her twenties. Perhaps it was the death of people she loved—her cousin Sophia, then her childhood friend Benjamin Newton. Perhaps it was a slow realization that the outer world could not hold her inner life. Perhaps it was her reading: the Bible, yes, but also the Romantics, and the letters of thinkers whose ideas pushed against the limits of convention and church.

Whatever the cause, by her thirties, she had begun her retreat.

She did not leave the house much. After a time, she stopped leaving it at all. She sent down notes instead of coming to the door. If guests arrived, she might speak to them through a slightly open doorway, her voice polite and clear but her body hidden. When a doctor came once, she let him in but refused to be examined.

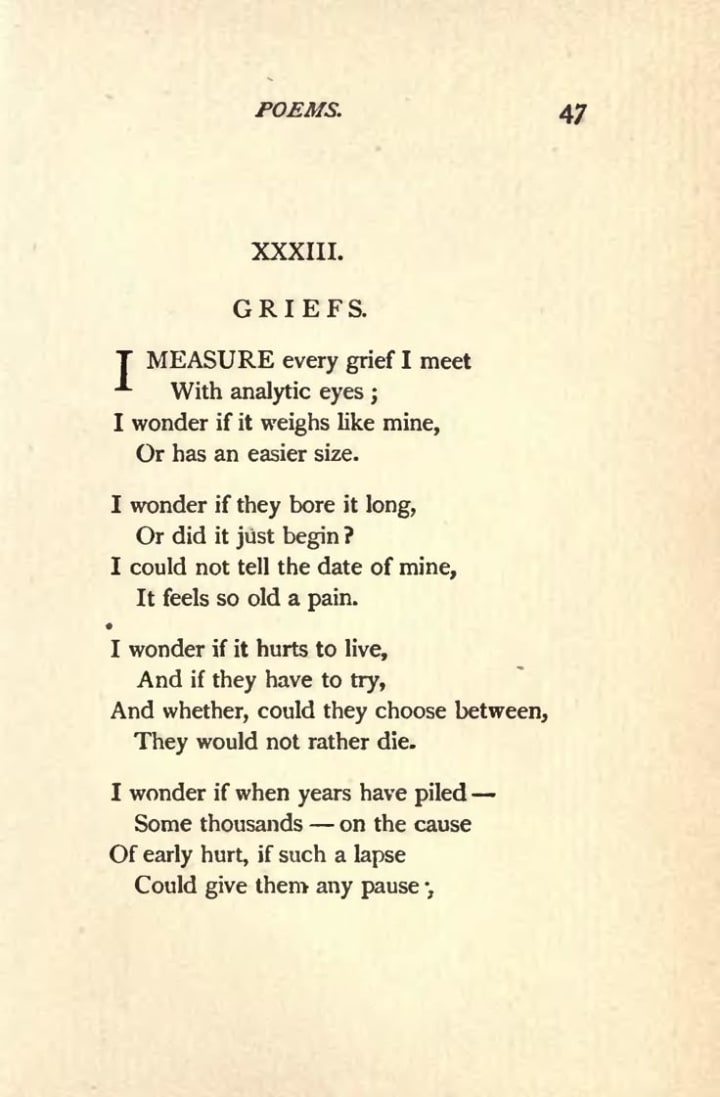

This did not mean she wasn’t living. She was, intensely. Every day, she wrote. Poems, scraps, fragments. Letters to friends that turned into masterpieces of elliptical thought and restrained emotion. She wrote to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a man of letters who had written a piece offering advice to young writers. She asked him if her verse was alive. “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” she wrote, and you can hear the tremble and challenge in it.

Higginson didn’t quite know what to make of her. He called her "partially cracked" in a letter to his wife, but he kept writing back. He visited her once. She wore white. He never quite understood her, but he never forgot her.

Emily’s letters are some of the most startling pieces of writing in the English language. They begin in ordinary tones, then suddenly veer into mystery, wit, longing, or devastating clarity. “Dear friend,” she might begin, then proceed to say something like, “I am out with lanterns, looking for myself.” She treated language like a tuning fork—striking it again and again until it rang just right.

As for the poems, she hid most of them. She copied them neatly into small fascicles—homemade booklets sewn with thread—and tucked them away in a drawer. A few were published during her lifetime, heavily edited and made to fit the bland tastes of the day. The editors inserted titles, regularized her dashes, and gave her poems rhymes she never wrote. She hated it. So she stopped sending them out.

Instead, she kept writing them for herself, and sometimes for others. She enclosed them in letters to friends, and though those friends might not have realized it, they were holding lightning.

Her world shrank in geography but expanded in depth. She walked her garden paths and studied bees. She wrote poems about death, eternity, and moments of pure, strange joy. She studied the light at different times of day as if it were a language. Her upstairs bedroom became the whole universe.

And still, she remained deeply connected to people—though rarely in person. Her letters were lifelines. To Susan Gilbert Dickinson, her sister-in-law and possibly the great love of her life, she wrote in tones that went from playful to elegiac. “I cannot make it better, Susie, because I have no pencil to mend the broken ‘sweet’ you gave me,” she once wrote. These weren’t casual correspondences. They were part of the private architecture of her world, as essential as the poems.

As she got older, death closed in. Friends died. Her father died. Her mother became ill, then passed away. Her writing did not stop, but it became starker, more precise, sometimes even angry. In one poem, she wrote: “After great pain, a formal feeling comes— / The Nerves sit ceremonious, like Tombs—”

She developed Bright’s disease, a kidney ailment that slowly wears the body down. She grew weaker. Her handwriting faltered. She still wore white. She still wrote.

On May 15, 1886, Emily Dickinson died in the house where she had written nearly 1,800 poems. Her coffin was carried through the back garden, past the flowers she had tended, to the Dickinson family plot in West Cemetery. She was 55.

After her death, her sister Lavinia found the cache of poems in the drawer. The scope of Emily’s work stunned her. The first volume of her poems was published in 1890. The world had missed her while she was alive, but it began to notice her now.

She never left Amherst, but her words did. Slowly, then all at once, they found readers who saw in them a truth no one else had dared to write. Pain, faith, doubt, joy, terror—written in short lines with slant rhymes and more dashes than grammar could tolerate. She did not seek fame. She sought something harder to name: to tell the truth, in her way.

Emily Dickinson lived quietly. But her poems are not quiet. They are fierce, strange, utterly alive.

And they are still speaking.

© 2025 Tim Carmichael. All rights reserved.

If you’re enjoying my stories or my poems, feel free to follow along for more. Thank you for reading and for your support.

About the Creator

Tim Carmichael

I am an Appalachian poet and cookbook author. I write about rural life, family, and the places I grew up around. My poetry and essays have appeared in Beautiful and Brutal Things, My latest book. Check it out on Amazon

Comments (3)

Thanks for this article, as a poet - I am fascinated by the lives of other poets. Would you consider reading something I wrote?

You definitely brought her out today, Tim.

“This did not mean she wasn’t living. She was, intensely.” Wow. To every writer who can resonate with this line. People who do not write think we’re “cracked” as you mentioned above. They think we’re the weirdo who just jots everything down like it’s a problem. Writers are so misunderstood ♥️