The Sacred Diagrams

"Fear the January spring, for March's envy will sting" - Polish proverb

Giordano found the book of sacred diagrams on a rock outcropping, on a lonely boulder in a glacial meadow – a field his small flock of sheep dutifully kept trim through their regular visits.

He didn’t know it was a book at first – what he saw, as he led his flock through a traverse between the jagged peaks of the Stawiańska valley, was a modest brown package perched on the rock, wrapped in butcher-paper and twine; and so very prominent, as if left there in wait of someone.

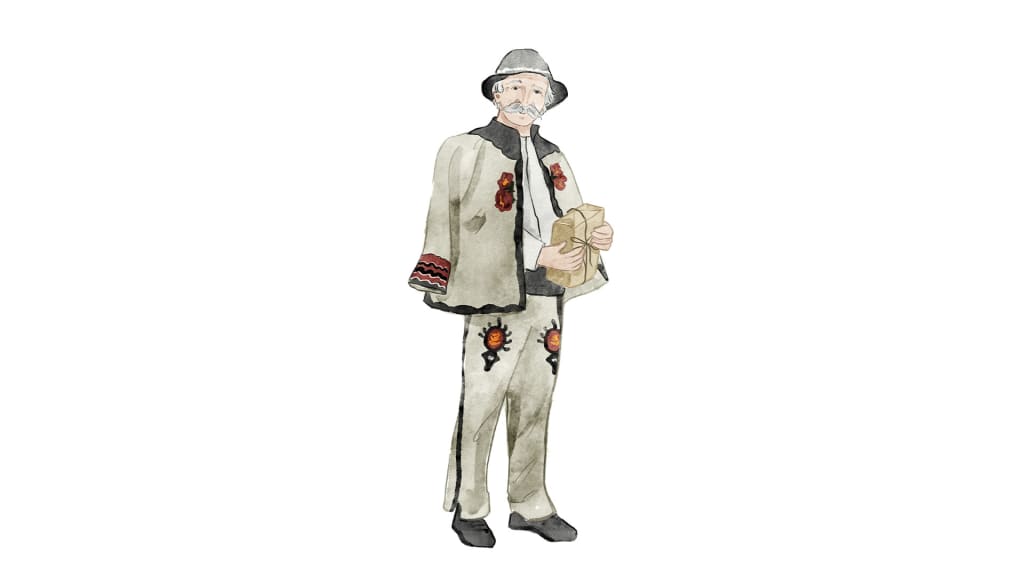

Giordano was a man that others of his mountain hamlet would describe as timid – still a bachelor well into his fifties, he kept to himself, tending to little but his few sheep and his forge, feeling blessed by good health and the fortune of living amidst such daily beauty.

He was not the type of man to pick up a package not meant for him.

And so the first time Giordano saw it, he left the package be, certain that its rightful owner would come along presently, that this curiosity would resolve like the other delightful surprises of a life amidst the peaks.

He hesitated the second time he came upon the package, and the third.

By his fourth time seeing the package in as many weeks, Giordano decided that its rightful owner would not find it, and so that evening, he took it back with him to the village.

“That’s not of anyone ‘ere, Giordano,” laughed Zygmunt at the bonfire that night, sweet bimber on his breath, a crackle of flying embers accenting the statement. The others at the gathering – shepherds, farmers, wives – concurred.

Helena, wife of Adam (and the better farmer of the two), prodded Giordano – “Open it, then. Let’s see what this is all about.” The conversation around the fire quieted down as the villagers waited for his response.

Giordano hesitated, looking at the eyes about him and seeing in them an attention he was not accustomed to. He smiled, nodded absently, and pulled at the ends of the package’s knot. The twine slipped off and the paper unfurled like a spring, revealing a simple blue book, bound in exquisitely sharp lines.

“It’s a Bible!” announced Zygmunt to the group – but already, Giordano saw that it was not. The book was… different, the cover a soft matte unlike any he’d ever seen. Giordano carefully opened it and began leafing through the pages – they were made of a thin, waxy… almost-paper, but not quite paper. It was a material Giordano had never felt before, and as he rubbed his fingers across it, he knew he wouldn’t be able to tear it if he tried.

But it was the figures on this paper that took Giordano’s breath away. They were diagrams, exquisite drawings of machines. Giordano flipped through the pages one by one. Some depicted devices and tools he was familiar with – a millstone, say – but improved in simple ways he would’ve never discovered on his own. Most of the pages, though, were windows into fantastical creations that Giordano could’ve never imagined, and scarcely understood even as he gazed upon them – whirling contraptions of blade and gear, of shaft and piston.

Those near enough to Giordano that they saw the pages by firelight began to move nearer, furrowing their brows at the strange pictures.

“Ya mute now, Giordo? Whatcha see there?” slurred Zygmunt.

Giordano turned the book around, showed the diagrams clearly to those around him. “It’s… a book of machines, of… inventions.”

There was curiosity in some of the faces around Giordano, but a passive disdain in most. None seemed to find much more significance in the book than in the other tales of that evening – of which the surprising recovery of Sebastian’s bull from three valleys hence was most engaging.

“So this is how they waste their time down the river, in those cities,” laughed Helena.

With that statement, most of the villagers knew the quick oddity past, and the din of fireside chatter resumed. Scarcely any of them heard Giordano murmur to himself – “no, I’ve seen much in the cities… this is not like… no, I’ve never seen any of these made this way.” Only Zygmunt, in his profound drunkenness, saw Giordano briskly turn and leave the bonfire, still staring intently at the pages before him.

-----

It took a few weeks for the people of the village to notice just how obsessed Giordano was with his sacred diagrams, and the full realization didn’t hit them till he sold nearly all his sheep to Adam.

“I just hope ‘e doesn’t ‘spect us to feed ‘im when ‘e’s got no way left to make a livelihood,” Olga commented one afternoon to Helena, the two of them hanging just-scrubbed clothes on lines of cord running from Helena’s barn to a nearby tree.

The sentiment was one shared by many in the hamlet. Ordinarily, villagers would care for each other – the flock is for its stragglers, as the saying went. But when one of them rejected all expectations set upon him, stopped undertaking honest work to indulge some fantastical whimsy… how could they condone such sloth?

“Oh come now,” responded Helena – “he’s a good man; curious, but good. He’s still the best forgesmith for leagues around, and whatever he’s seen in that book, it can’t all be bad. That new plow he made for Henryk, you heard? Claims it doesn’t even need an oxen-team, just a horse to pull it.”

Behind her gild of optimism, though, Helena was troubled, and Olga could see this. Henryk had used the plow exactly once before leaving it in the forest. It worked, all right, but it worked too easily, practically floating through the dirt – Henryk didn’t trust what something like that would do to his alpine soil, barren as it was already.

And the plow was still the most useful contraption to come out of Giordano’s hut.

Increasingly, the villagers heard strange machine rumbles within, and knew to stay well away – but even from a distance, they saw the tripods Giordano brought out, with narrow, slightly tapering horns upon them, horns which grew larger with every passing week. Horns which they saw Giordano pointing skyward and staring through long into the night.

It was only when Giordano came down to the main village row, to the firepit where they usually gathered, that anyone felt compelled to speak with him. He was so eager now, still reserved, but with a light upon his face that no one had seen since his mother had passed a decade prior – and it was only through curtness that the villagers could prevent him from raving about his mad creations, could focus the conversation on the few bits of forgework they still needed his expertise for, while they tried to find anyone but him to mend their tools.

“What’s with those horns a yers?” Zygmunt blurted out one night, the bimber having washed away all polite inhibitions.

“They’re sky-glasses,” responded Giordano quietly but earnestly. “Some of the very first diagrams in the book show how to build them, and then… what to look for among the stars. The diagrams show where we… live among the stars, if that makes sense, and… well, this is so much later, near the end of the book, but – the diagrams show how to build these fantastic coaches that could travel to the stars. I know how it sounds, but… somehow, everything I’ve built from the diagrams so far has worked!”

Giordano was so happy, so eager to share, that he didn’t notice the silence around him – nor the exchanged glances halfway between revulsion and fear.

“Of course, I think it would take me the rest of my life just to understand the first tenth of the book. But what’s in there… what our children could build – it’s wondrous!”

“Not my children,” said Helena coldly, the words knocking the wind from Giordano.

“No, I’m sorry, I just mean…” Giordano stammered.

“I think t'id be best if ye stopped this nonsense, and got back to honest work,” declared Zygmunt, his words firm. Heads nodded around him.

If Giordano heard the threat in Zygmunt’s suggestion, he didn’t understand it – in the following weeks, the rumbles from his hut grew louder and more consistent, and he began bringing to the main village contraptions and tools which he seemed to hope the villagers might use in the nearing harvest-season: A cart of rotating scythes, a mechanical thrasher of some sort, a haychute which could twine dried crop to bundles.

Giordano demonstrated how each of these worked, left them to be used by anyone who desired. But none dared touch the unholy things.

One day, as Giordano wheeled his newest creation down to the main way, he saw what remained of the previous machines – splinters of wood and smashed curves of metal. He sagged, turned around, and drifted home.

And yet he continued to build.

-----

The action came swiftly, and it came by the darkest of moonless nights.

Zygmunt and his brother drove the angled barricade into the door of Giordano’s hut, and the rest of the villagers knew they could finally break the silence they’d held carefully through their climb up the hill.

Fire passed quickly from one torch to the next, starting at the rear of the crowd and soon spanning the full breadth of the encirclement. And then the torches began to fly – some landing at the foot of the house’s wooden walls and slowly beginning to lick those ponderous timbers, others flaring into quick conflagration across the straw roof.

A broad woman marched up to one of the hut’s few windows and smashed her torch against it again and again, until the glass gave way with a crunch, and she could push the torch through, letting it fall away inside.

The faces of the villagers were awash with sweat, with the trepid joy of a mob’s duty, with the fear of something that could never be undone.

It wasn’t until the hut took on the ghastly specter of a skeleton ablaze, until the villagers all had to step back more than they’d expected, to shield their faces with arms upraised against the pillar of blistering heat – that they finally heard the screams.

The screams that didn’t soon whimper off, but dragged on for first seconds, and then minutes – the screams of an absolute terror, of unimaginable pain consuming a body whole, of a helpless retching panic against the sudden permanence of death.

The screams that finally turned to silence, a silence which told the villagers that their thankless task was over. That both the vile man and his sick book were gone forever.

And without a word to each other – without a glance at each other – the villagers turned from the embers of what they’d done, and each walked home in darkness, alone.

-----

In the fading light of the next sunset, a boy from the mountain hamlet walked towards the smoldering blight that used to be Giordano’s home. Though not one of the villagers had spoken to him of it, he understood the prior night well.

The pile was all black wood and grey ash, with smoke still patiently streaming like a dark blood from amidst the mangled body.

The boy scanned the pile nervously, and then he saw it – a neat rectangle of sharp blue, wedged under a beam near the far edge of the wreckage. He walked over, and with a quick dash into the heat, he snagged the book and stepped back with it. He was ready to drop the thing, but it was cool to the touch – and as he examined it more closely, he found not a single blemish from the fire upon it.

The boy quickly looked around, reassured himself that he was alone. He sat down, opened the book, and began to turn its pages one by one.

And his eyes grew wide at the sacred diagrams within.

About the Creator

Kasper Kubica

Physics grad, fascinated with aviation and the future, currently founder of Carpe (mycarpe.com).

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.