The Good Memory Book

A veteran of the Iraq War struggles with his injuries

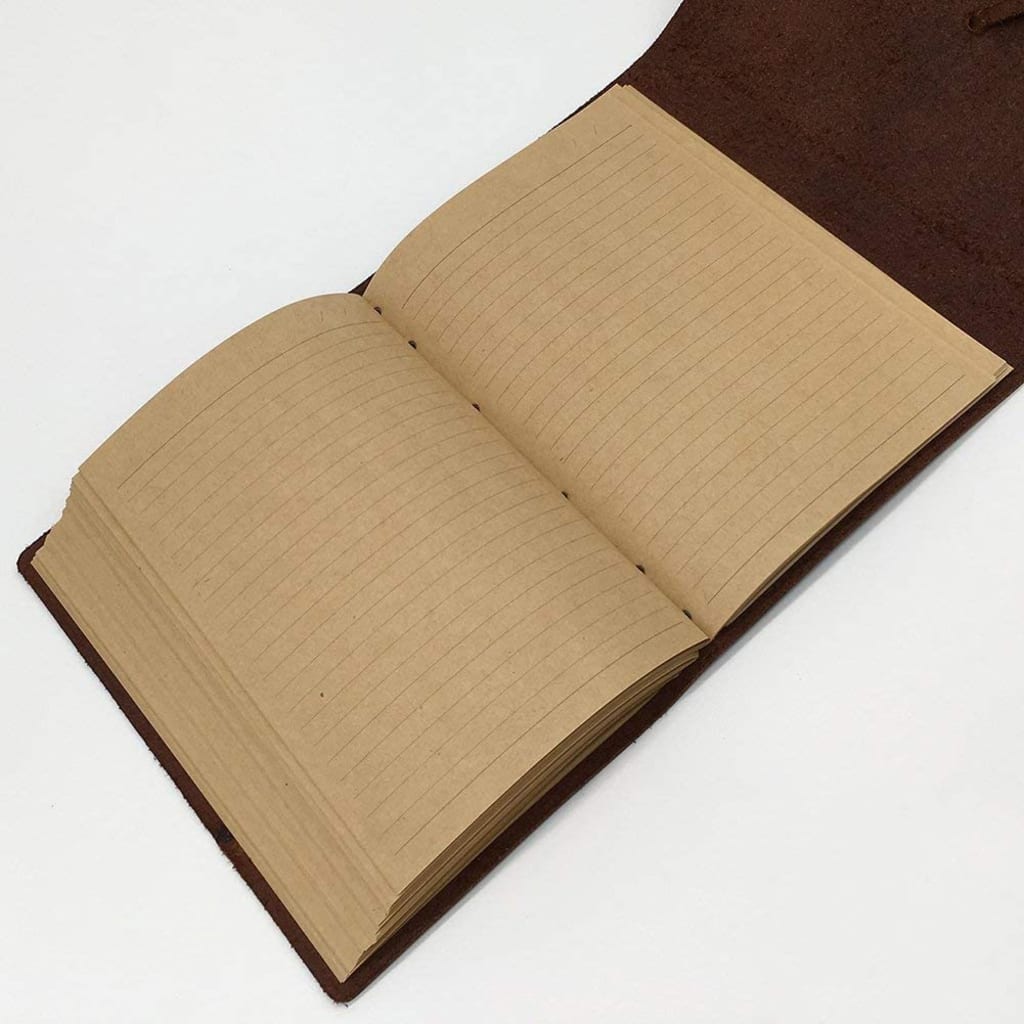

In the evenings he would hear their voices, coarse, full of regrets and memories that were stronger than his own. In the mornings he could hear birds outside his hospital window, singing a song, mysterious to man. In the twinkling light of dusk, the nurse would come in and change his bedding. She would check his vital signs, humming the same droll hum each time. She was Filipina, or so he thought, and her body was small and round, and her smile was warm but lacking character, as if she practiced it in a mirror until she got it right, a pre-packaged smile for the sad sack vets she cared for in the grey hospital that so many souls were chained too. The nurse rarely spoke of anything beside the weather and the barely held together man that was her charge wondered if she were part of the doctors’ experiment to revive what he used to be. What the brown leather-bound book sitting at the end of his bed like an attentive dog was supposed to help cure.

The nurse spoke of the coming chill of fall, the lessening of light and the tanning of the leaves. He remembered, or thought he did, the smell of fall. The air, thick with the scent of fireplaces, so crisp and cool he thought that as a child he could take a bite of it, and in that moment savor the flavor of pumpkin and apple pies that must have added to the smell of the coming winter.

On the days he would sit across from the therapist he would notice how her eyes fought a losing battle with the side of his head, which still ached and throbbed, especially when the chill air the Filipina nurse spoke of found him as he wandered through the gardens of the VA hospital, before an orderly or a nurse rushed out to grab him and take him back to his bed.

She was doing it again, the doctor who had given him the brown book, what she had described as “essential” to his therapy. He had caught her staring at the mound of purple contusions, mostly hairless, but patchy with thin, pathetic strands struggling to gain a foothold. The doctor looked away as he caught her, and she readjusted herself on her seat and looked down at the yellow notepad resting in her lap. She cleared her throat and pushed the button atop her pen rapidly.

“What have you written?” she would say not looking up, her cheeks reddening.

“Written?” he would say.

The doctor, maybe as before, would point down to her patient’s lap and would say, on the verge of sighing:

“The book... your good memory book... did you write anything down? Has anything come back to you? About the time before?”

His eyes would glaze, and his body was there but he was not. The plant in the corner of the room needed water and he wondered what type of color ink his pen was and the ceiling fan was too loud or did it need to be turned on and the doctor was a woman and what was she doing in the room?

“Henry,” the doctor would say.

Yes, his name was Henry, and he was 23 and living in Seattle and he was a soldier who had been in a land where the sun was so hot, and so brutal, your skin would bubble and melt if you touched steel with an ungloved hand. A land where the children’s eyes were filled with fear and hatred. A place where they fought an enemy that was never seen, for reasons he couldn’t remember. The time and place before the contusions had appeared on the side of his head. A place where a man that he remembered as a friend and a brother who he loved, had disappeared in a flash and a bang. And then he was with a Filipina nurse who spoke of fall, or was it spring? And who the hell was this woman in the room with him and why were her eyes disapproving behind a set of black, thin-framed glasses?

“The good memory book.” he said once to her. Or twice, or a thousand times.

“It’s supposed to help you,” someone had said. “You write down the good memories before the attack.... To help your memory.”

At that he had picked up the book and turned it over. The leather was smooth and smelled of what he knew to be the interior of a car his father had once owned. A car he was not allowed to eat anything in. Henry remembered being frightened once, when he had spilled soda, or water, or coffee in the back seat. But his mother had come out to help him and shrugged her shoulders and said accidents happen. When they had cleaned up the mess, she had hugged him and whispered in his ear, “No need to tell your father.” He felt her heartbeat and smelled her perfume. Her hair was soft as it always was, in the moment her hair had caressed his face she had hugged him closer, tighter, and Henry knew he was loved.

There’s something, he thought. A good memory.

He picked up a pen or a pencil and marveled at the browning leaves. As he opened the book with its volumes of blank lines, he wondered what was for dinner and if the Filipina maid was coming to clean up his room and where a man he had loved as a brother with a laugh that made all those around him, even the enemy they fought, be at ease.

“There’s nothing to write,” he told the lady doctor before, or after, or never. She had stomped her foot at that, or thrown her pen, or nodded and looked down at her notes.

He opened the book once and saw a line scribbled in familiar writing, a single soul in two bodies. He wondered what that meant and someone in the hallway laughed at a joke he had missed the punch line to. A laugh.

Outside the air was cold but he could feel the warmth of the heater in his room. Henry put pencil to paper and wrote about a staggered line of Humvees riding slowly out of a base, of a turn in the road and a dead dog by the side of a road. How wiring stuck out of its butt and even the flies knew to stay away from it. He stopped. Decided to change course. Henry could have written of the sound, so loud it made his ears bleed. The concussion, how his teeth vibrated after the flash that blinded him and he could have written of the feeling of being picked up off the ground, how he felt suspended in the air as the steel around him buckled and groaned and the peculiar feeling of knowing he was going to make it came into focus as the steel world around him collapsed. How his next thought coming in a thousandth of a second before the last was how Superman was a punk for getting beaten by a green rock, while he would survive this. He could have written of the smoke and the fire, of the warmth of something oozing down his face and filling his mouth and how his left eye stopped functioning. How there were screams round him and shooting and hands grabbing at him and the suffocating, lung burning powder from fire extinguishers.

But Henry did not write this for somehow, he remembered, that this was a good memory book.

Henry wrote of the song they played in the vehicle at the time, the conversation he had with a man he loved who drove the truck, the sound of his voice as they turned the bend and a dog with wires came into view. He wrote of Halloween as a child, of a Golden Retriever he named Sam, of summer nights as a teen, of a first kiss, awkward and thrilling in the same breath with a girl named Marie, he wrote of his mother, the softness of her hair, and his father who cried when his son told him he was going to war, and he wrote of the spring and the fall and the fireplace scented air, and the apple pie. And finally, of a man who he loved who was braver and more noble than Henry could ever hope to be who was gone.

The Filipina nurse came in and he put the book away and watched her set his meal down. She spoke of the weather again and when she met eyes with him, something she had never done for long, he put his hand on hers and asked,

“Who was I? Before the war?”

She took his hand in return and said, “you were Henry.”

About the Creator

Stan Moroncini

I was born and raised in Los Angeles, the son of immigrants from Latin America. I served in the army for 15 years, completed two tours of duty to Iraq and Afghanistan and have loved writing since I can remember.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.