The Day I Found Out My Grandfather Was a Spy

He was the man who taught me how to ride a bike, make tea just right, and keep secrets. But none were as big as the one he took to his grave—until I uncovered the truth.

I always thought my grandfather was just a quiet man with a love for crossword puzzles and gardening. He wasn’t the kind of person who talked too much, but when he did, it was with purpose. I was fifteen when he passed away, and though I grieved like any grandson would, I had no idea that the real story of his life hadn’t even begun for me.

We called him Baba. He wore thick glasses, loved jazz records, and kept a locked drawer in his study that no one was allowed to touch. “Just boring tax papers,” he’d say with a wink. I never questioned it.

It wasn’t until three years after his death that I stumbled onto the truth.

It began with a call from my mother. She’d finally decided to clear out Baba’s old study, and while going through his desk, she found something odd — a leather notebook wrapped in a faded cloth and tied with string.

“Do you want it?” she asked.

“Sure,” I said, not thinking much of it.

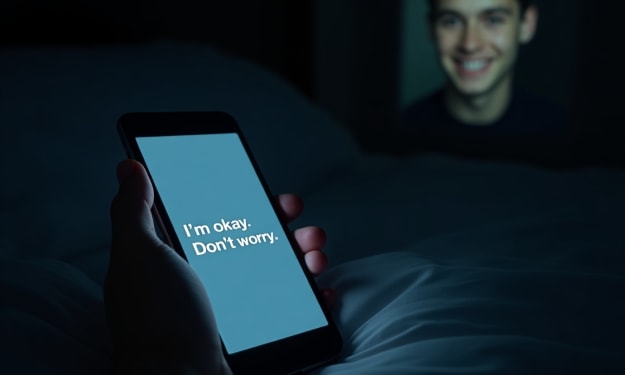

When I opened it later that night, I wasn’t prepared.

The notebook wasn’t a diary — not really. It was a mix of dates, locations, strange initials, and short coded messages. At first, I thought it might just be some kind of made-up game he used to play with himself. But then I found a folded letter tucked into the back page.

The letter was dated 1964 and had no salutation—just a name at the bottom: “Directorate B”. In short, cold language, it confirmed the assignment of a “field operative” to monitor and occasionally relay intel regarding “developments in local civil structures and foreign movements.”

I Googled the term “Directorate B.”

Turns out it was a real division within the British Secret Intelligence Service during the Cold War.

I froze.

Was this real? Was Baba…a spy?

The idea seemed ridiculous. But something inside me clicked. The strange way he used to scan public spaces. The way he taught me to notice people’s shoes before their faces. His obsession with maps, and how he always spoke in vague, indirect language when I asked about his youth.

I kept digging.

Over the next few weeks, I went through old letters, photos, and anything I could find. There were odd travel dates. Receipts from hotels in Eastern Europe. A photograph of him in front of a building in Berlin—except he’d never mentioned visiting Germany, ever.

I took what I had and contacted a retired intelligence historian I found online. He confirmed that some of the abbreviations in the notebook were legitimate operational codes used in the 1950s and 60s. One of them was tied to surveillance operations involving British diplomatic stations during the height of Cold War paranoia.

By now, I wasn’t just curious—I was obsessed.

I requested declassified archives through the Freedom of Information Act. Six months later, I received redacted documents that didn’t mention my grandfather by name—but described a man with his exact profile, stationed in Eastern Europe under a fabricated identity. His mission: gather low-level intel and build local trust, mainly through “civilian social embedding.”

That was Baba. That had to be him.

It took a while for it to settle. I wasn’t angry, just…shocked. This man who had read me bedtime stories and taught me patience in gardening had once carried out secret operations for the British government.

He had led two lives. One public. One buried.

And he never let the second bleed into the first.

But the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. The silence. The caution. The quiet strength he carried. He had protected his secret not to lie—but to protect us. Maybe even to protect the people he once watched.

I never told my mother. Maybe one day I will.

For now, I keep the notebook locked away.

But sometimes, when I walk through the park or board a crowded train, I find myself watching the people around me — shoes first, just like Baba taught me.

And I wonder how many of us are walking mysteries.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.