The Adventure of the Mechanical Mind

By Dr. John H. Watson

It was on a wet Thursday in March of 1890 when Holmes received the telegram that would lead us into one of the most singular and intellectually provocative cases of our long acquaintance. I had returned from my morning rounds to find my friend in a state of what Mrs. Hudson delicately termed "chemical enthusiasm"—the air in our Baker Street sitting room was tinged with ozone, and Holmes was adjusting the current on a makeshift galvanic coil connected to the skeleton of a dead rat.

"Reanimation, Watson," he said cheerfully. "Strictly theoretical. The heart remains stubborn."

He handed me the note before I could formulate a protest.

> "URGENT. DEATH DURING DEMONSTRATION AT ROYAL SOCIETY. POSSIBLE FOUL PLAY. REQUEST YOUR ATTENTION DISCREETLY. – LORD PENHALLOW"

"Lord Penhallow?" I said. "The industrialist?"

"The same. Patron of science, public scourge of superstition, and, according to the Times, financier of the reconstructed Babbage Engine recently installed at the Royal Society."

I looked again at the telegram. "A death during the demonstration? You think it could be related to the machine?"

"I think," Holmes said, donning his coat, "that any death occurring in the presence of a calculating engine built to out-think men is worth our attention. Come, Watson—the fog will not lift itself."

---

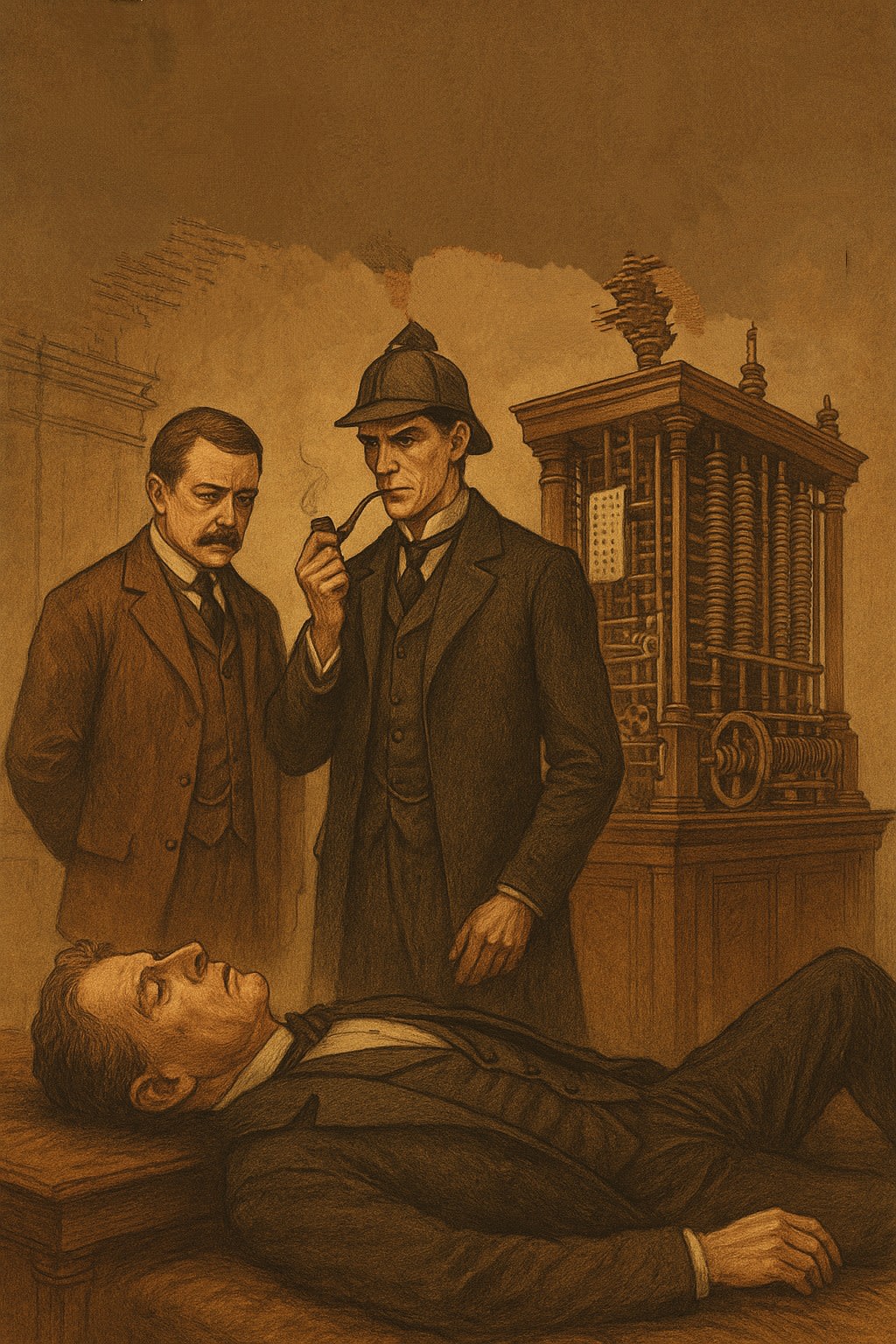

We arrived at the Royal Society shortly after noon to find the great exhibition hall cordoned off. The Analytical Engine—a towering brass-and-steel edifice covered in dials, cranks, and punch card readers—stood inert beneath a velvet drape, like some slumbering beast. Around it, gentlemen in mourning coats whispered in anxious tones. Holmes was recognized instantly and led through.

The body of Dr. Erasmus Finch, Fellow of the Society and longtime professor of mathematics at King's College, lay slumped in a lecture chair. His eyes were closed, his limbs relaxed, and to the untrained observer, he might have appeared merely asleep—save for the slight blue tinge about his lips.

"No sign of violence," I observed after a cursory examination. "But the face is… peaceful."

"Which rules out many poisons," Holmes murmured. "And yet, no convulsion, no struggle. Curious. Was he speaking when he collapsed?"

One of the officials—a young assistant curator named Geoffrey Moffat—nodded. "He'd just finished operating the Engine. It printed something—a strip of punched tape. He stared at it, grew pale, and then simply… ceased."

Holmes took the slip, examined it. "A sequence of binary notations, followed by a phrase in crude Latin: Mentem mortalis imitatur."

I translated aloud: "It imitates the mind of man."

"Not quite," Holmes corrected. "A closer reading: 'It imitates the mortal mind.' A subtle distinction—and likely one meant to be noticed."

He turned the tape in his fingers. "Tell me, Mr. Moffat. Who last interacted with the Engine before Dr. Finch?"

"Mr. Thomas Ketteridge," Moffat replied, hesitating. "He's the engineer who built it. But he left before the demonstration. Finch was always the one to handle public matters."

"Why leave just before the unveiling of your life's work?"

Moffat looked uneasy. "Ketteridge and Finch… had disagreements. About credit. About the future of the machine."

"Was Ketteridge here when Finch died?"

"No. But Lord Penhallow was."

Holmes was silent a moment. Then he said softly, "A man dies at the climax of a demonstration—while activating a machine meant to simulate the human mind. And his last words are not spoken but encoded. Remarkable."

---

We found Lord Penhallow in the Society's library, nursing a glass of brandy with less stoicism than one might expect from a peer of the realm. He was a broad man, florid of complexion and evidently shaken.

"I'll be damned if it wasn't the Engine itself," he muttered. "Thing was hissing and clanking like it had a mind of its own. And then that message…"

Holmes raised an eyebrow. "You believe the machine killed him?"

"Of course not," Penhallow said irritably. "But the timing, the message—it unsettled the crowd. Some are already calling it a blasphemy."

"You funded the reconstruction?" Holmes asked.

"Yes. Ketteridge brought me the design. Said Babbage's original plans were sound—he just lacked the materials and political support. We built it faithfully. Or so I thought."

"And Finch?"

Penhallow hesitated. "Finch was a genius. But proud. He wanted to delay the launch. Said the Engine had… anomalies. I thought he was jealous of Ketteridge. Now I don't know."

Holmes narrowed his eyes. "What sort of anomalies?"

"Finch said the machine sometimes produced calculations no one had input. As if it were… anticipating. I thought it was nonsense."

---

We interviewed Thomas Ketteridge that evening at his modest flat near King's Cross. He was a lean, nervous man with ink-stained cuffs and a clockmaker's dexterity. He greeted us with little warmth.

"I didn't kill Erasmus," he said at once. "I admired him—even envied him. But I didn't harm him."

"Then you won't mind if I ask about the Engine's final output," Holmes said. "The Latin phrase. It wasn't part of the code Finch demonstrated."

"No," Ketteridge said slowly. "But it was embedded in the machine's memory cards. As a failsafe—a kind of digital watermark. Only Finch and I knew it existed. It would appear only if someone altered the operating logic."

"Altered it how?"

"Inserted false logic into a valid card. Like slipping a forged page into a ledger."

"Could such a change," I asked, "cause a physical reaction from the Engine?"

Ketteridge looked grave. "The machine isn't dangerous in itself. But its punch system controls electrical relays. Finch used them for dramatic effect—sparks, motorized output arms. If someone calibrated those wrong..."

"A discharge," Holmes finished. "Through the control levers."

"A fatal one," Ketteridge confirmed.

---

That evening, back at Baker Street, Holmes stared long into the fire. He picked up the punch tape again and tapped it against his knee.

"Ketteridge did not flee, nor did he gain from Finch's death," he said. "Penhallow's stake is financial, not personal. No—this is a crime of ideas. Pride. Vindication."

He turned to me. "There was one detail you may have missed, Watson. Moffat. He filed the patent application for the modified Engine last week—listing only himself as inventor."

I stared. "You think—?"

"I think Finch discovered the deception. And Moffat, knowing the machine's systems, arranged a fatal accident masked as performance failure. The Latin phrase was Finch's signal to us. A dying man's final clue, hidden in the one place he trusted: the logic of the machine."

---

Epilogue

Geoffrey Moffat was arrested within days. Holmes presented the case with mathematical precision: access to the punch system, motive in the form of sole inventorship, and the clever manipulation of the Engine's relays to deliver a precise, lethal shock masked by performance theatrics.

Finch, it seemed, had uncovered the forgery the night before the demonstration. Moffat, fearing ruin, modified a logic card to send a discharge through the brass hand-lever when Finch initiated the finale. The phrase Mentem mortalis imitatur was both a clue and a condemnation.

Holmes later demonstrated the very card that triggered the Engine’s final message. Using a magnifying lens and the light from a chemical lamp, he showed me the altered punch: a seemingly minor deviation that shifted the relay current through the brass lever instead of the insulated guide.

"Watson," he said, his voice low, "this was not merely a murder. It was a message. Finch left us proof that even a machine designed for cold logic could be used in the name of truth—when men fail to act."

As we left the courtroom, Holmes paused on the steps.

"Curious, isn't it? A machine designed to imitate thought becomes the vessel of a dying man's final message."

"And yet it took your mind to interpret it," I said.

He smiled faintly. "The day machines no longer require us to solve their mysteries, Watson, is the day I retire."

And with that, he turned into the fog, as the gaslights flickered against the dusk.

Author's Note: I will confess that this was a collaboration between myself and an AI, which consisted of much back and forth between myself and the machine. This seems appropriate given the nature of the story. This may be the start of a series, which may include a story or two with Holmes using the machine as an aid to solving a mystery.

Historically, Charles Babbage was never actually able to construct a completed version of his machine. The first complete Babbage Engine was completed in London in 2002, 153 years after it was designed. Difference Engine No. 2, built faithfully to the original drawings, consists of 8,000 parts, weighs five tons, and measures 11 feet long.

Comments (1)

This case sounds fascinating. The idea of a death during a demonstration of a super-advanced calculating engine is really intriguing. I wonder what kind of foul play could be involved. And how did Holmes plan to start his investigation? Did he think the engine itself was malfunctioning or was there something more sinister going on?