Human-imprinted birds have no fear of people. They believe themselves to be human, and their strange behaviour makes them both unacceptable to their own kind and a danger to their adopted species. Toyosi had a theory that people in Colony One were a little like these birds.

The Colony lay at the centre of a human-made recess in Mount Bintumani, Sierra Leone. They had always called it a cave, just as they called older family friends ‘Auntie’ and ‘Uncle’. Over four generations the population had grown from a couple of hundred to nearly a thousand. Colony One was the official name. The Nigerian telecoms billionaire Goodluck Akinjide bet his entire fortune on survival, paying the Sierra Leonian government for its silence and financing the Colony. By the time the secret got out, the blast doors were closed and the Kongolo Asteroid impact of 2031 was just weeks away.

When the two-mile wide asteroid struck near Kongolo in the Democratic Republic of Congo, it created shockwaves of half a million megatons that emanated out in a five hundred mile radius, setting off wildfires and creating clouds of dust and debris that blocked out the sun for many years. Those species of plants and animals that did not die a quick death from the impact mostly died a slow one. Those humans who could not find shelter were not spared.

2155

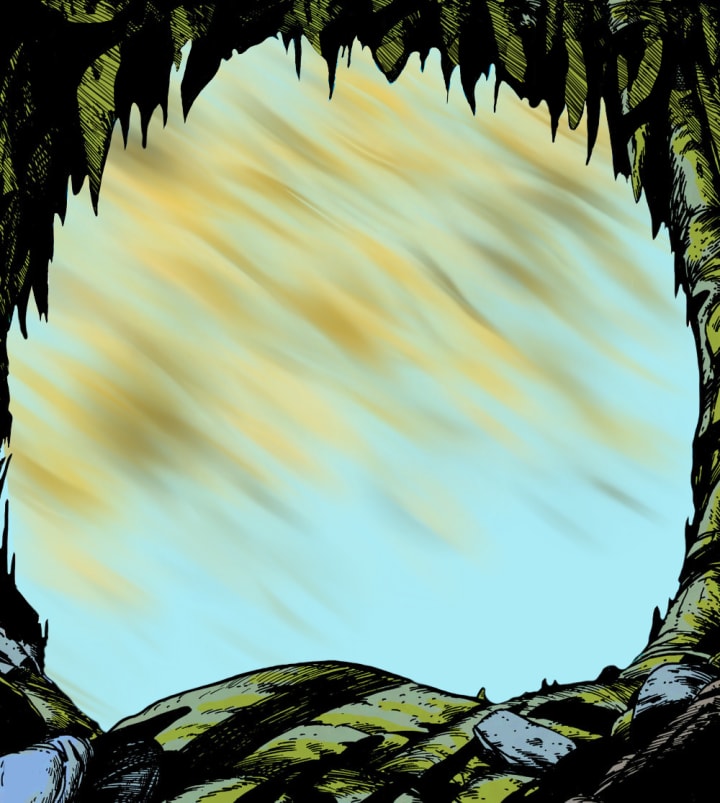

Today, Toyosi was on her usual walk outside the Colony. The cave was a wonder. One hundred and twenty-three acres across and half a mile tall at its highest point. Most importantly, it was stable. The ceiling was perfectly arched despite its great size, and the mix of glasswool and soil insulation combined with reinforcement steel to give the whole structure a satisfyingly uniform appearance. Toyosi felt safe looking up at that every day.

The colonists never grew complacent about training up structural engineers. Toyosi would know – she was one of them. She was a third-generation colonist who had grown up with Yoruba as her main language. About half of the original colonists had been from the south west of Nigeria and that legacy persisted in the culture of the cave. Walking out to the cave mouth, though, a variety of other languages could be heard – Mende, Krio, Xhosa, Twi, Amharic, Bantu, Swahili, pidgin English. French was the language of the younger people. Toyosi heard her trainees chatting away in that strange tongue during breaks.

They had opened up the cave sixteen years ago, a few months before Toyosi’s twentieth birthday. Before that the thick blast doors were permanently shut to protect them from the foul air outside. As lines of communication were established with the various pockets of human survival, the envy and mistrust of the outsiders became clear almost immediately. They had not forgotten the secrecy of Colony One’s beginnings. There were also some who simply could not bear to see these Africans faring so much better than most. For in addition to their health, security and high levels of education, the colonists had opened the doors to discover they were also rich. This was not the result of any great foresight from their forbears, however. It was an accident of supply and demand.

2135

‘I would have fired the world’s entire arsenal of baked beans at it.’ Esme laughed as she said this.

‘Baked beans? Come on, Esme!’ Toyosi also got the giggles now.

‘Baked beans. I’m serious. Still in their cans, though. With the right spread, those little metal missiles could have broken up the asteroid. Or at least made it miss Earth.’ Esme paused, a smile playing on her face. ‘Admit it. I’m a genius.’

‘Hmm. You’re definitely… something. One of a kind. No denying that! Okay. My turn.’ Toyosi rubbed her foot against Esme’s. They were lying side by side on her bed, both still in their school uniform of grey pinafores and white shirts. The odd socks on their feet were part of their daily rebellion against that uniform. ‘Got it! I would have found a way to get the world’s supply of rubber bands into orbit. There must have been billions of them back then. Trillions, even. Then when the asteroid came it would just have bounced off.’

‘Ugh. So many problems with that. First, how would you actually get them all up there? Second, trillions of rubber bands around the earth would have completely blocked out the sun. Permanent winter and darkness? Not great. And third, the asteroid would probably still have punched a hole through them anyway.’

‘You’re right. They’re no baked beans. Ouch!’ Toyosi had just been elbowed in the ribs by Esme. ‘Okay, seriously. You want to hear a crazy one I was watching a video about this morning?’

‘Crazier than rubber bands? Surely this cannot be.’

‘Ha ha. Yes. Okay. Some scientists thought if they could get drones up there to paint the asteroid white, the force of it reflecting the sun’s rays would have changed its trajectory.’

‘That might just be the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard.’ Esme's response came almost before Toyosi had finished speaking.

‘Whaaat? How can you say that? The science backed it up!’

‘So you believe it?’

‘Well, not that I want to agree with you. Like, in any way at all. Buuuut, to believe it, I guess I would also need to believe the outsiders could ever get themselves together and organise something like that. Which, you know, obviously they didn’t ’cause here we are. Living in a cave.’

‘Yeah. Idiots.’ Esme twirled the end of one of her cornrow plaits. ‘Maybe it’ll be different when the doors open.’

‘If they open.’

‘When. Those doors have to open sometime. And one hundred years is more than long enough for the worst of the air pollution to have settled. Mr. Cyprian was literally just saying so in Geography yesterday. Plus, isn’t that what your dad says too?’

‘Yeah, I guess. Do you really think you’d ever go out there, though?’

‘Not without you.’ Esme turned and kissed Toyosi lightly on the cheek, her lips lingering as she inhaled her girlfriend’s scent. ‘Or maybe I’ll let you go out first, like one of those probes your dad designs. If you survive, then I’ll think about it. Maybe.’ This time it was Toyosi who elbowed Esme.

2155

Natural light only came into the cave mouth for about an hour each day. The hour varied according to the time of year, but Toyosi always planned her day around it. You had to really get close to the cave mouth to fully appreciate the light.

Her father Appiah would have loved to see the blast doors open. His life’s work had been leading up to that goal. It had been eighteen years now since the fire. Toyosi had now lived more of her life without him than with him. That hurt. Especially as she had seen so little of him towards the end. As Mission Director for the quarterly probe launches, her father had barely had time to sleep. With the doors open, perhaps he could have taken a walk every now and then.

Each launch was beset by problems. Toyosi had studied the Probe Program as an undergraduate. The engineers before her father’s time had mainly contended with the fog of dust and ash outside the cave that threw so many probes off course. Appiah’s team complained about working with outdated components that had been recycled and repurposed dozens upon dozens of times. In addition, they could not communicate with the probes once they exited a tiny opening in the thick blast doors. The little machines had to carry out their tasks autonomously and then find their own way back. Consequently, artificial intelligence and computer programming were two areas where the Colony did not slack. And yet, they did still occasionally lose a probe and each loss was felt keenly. They could not spare the materials. Also, a probe that did not make it home took terabytes of data with it into oblivion, delaying their analysis of conditions outside the cave.

Toyosi remembered the atmosphere in the Colony on days after a probe had been lost. At home, barely a word would be spoken and then at school it was the same, everyone shuffling around like the gravity in the cave had increased. Even Esme could be weird with her. Things began to change in her mid-teens, around the same time that her father became so much more busy at work. By then even on days when the probes came back without any issues, the Colony would crackle with tension and anger.

Toyosi walked on, determined not to miss the light.

2147

Esme had only walked to the cave mouth once. She was one of those who left. With great difficulty and a hardening of her heart, Toyosi could sometimes go through a day without thinking about her. One day but never two.

Toyosi was heading home from her first job in the planning department when she saw Esme standing outside. She recognized her almost immediately. Or rather, her eyes were drawn to a young woman in one of those baggy khaki jumpsuits the outsiders loved so much. It was Esme. She had a giddy look on her face, lacking the contrition that Toyosi needed. Still beautiful, though, even if she wore her hair in an unruly afro now rather than the tight, intricate plaits of their youth. Toyosi walked past her, pretending not to have seen.

‘Hey-yeh! Toyosi, wait up!’ Esme fell in with Toyosi, who was marching at some pace.

‘What are you doing here, Esme?’

‘What kind of hello is that?’

‘I don’t owe you any kind of hello.’ Toyosi stopped abruptly, leaving Esme to take a few more steps before she also stopped. ‘What did you expect me to do? Run up and give you a big hug? Prostrate myself? Invite you back to my place to fool around? Tell me, Esme, what exactly is it you want, showing up like this?’ There was no immediate response. After a minute of heavy silence, she began walking again.

‘So, how have the seizures been lately?’ Esme said this gently and she saw Toyosi open her mouth to reply and then snap it shut. ‘I guess they’ve been able to get you better meds now, at least...?’ Toyosi's face was now an impassive mask. Esme changed tack. ‘I see there’s been building work going on. And so many people carrying babies! The Colony is changing.’ Esme spoke expansively now, trying to recapture the familiar tone of past conversations.

‘What, you expected things to stand still while we all waited for you to come back for a visit?’

‘That’s not what I meant, Toyosi. And I think you know it.’

‘I don’t, actually. I don't know anything about you, really. Not anymore. Maybe back then I was all wrong too. Like, even after we broke up. In those couple of years before you left, you’d always come by and see me on the anniversary of the fire. That all stopped when you left. It was ten years just the other day and you didn’t even reach out. I’ve spoken to some of the other guys from school and they all say the same thing. It’s like we stopped existing when you got on that transport.’

‘I wanted to call you, Titi. Really-’

‘Don’t call me that. Toyosi is just fine.’

‘Sorry. Well, I really did want to call you. Or at least send a message or something. I guess I just didn’t know what to say. How to get started. Look, Toyosi… I’m sorry, okay. I wanted you to come with me, remember?’

‘Of course. I still laugh about it now.’

‘I know you’re angry, Toyosi, but there’s no need for that.’

‘Who’s angry? If I’m angry about anything it’s that some random woman who used to be my girlfriend shows up outside my work without telling me she was coming. Not a word, not a message in six years and then you just appear. Standing there like a mumu wearing… like, what exactly is it you’re even wearing? Is this really how people dress out there?’

‘I didn’t come here to be insulted, Toyosi. I don’t have to take this from anyone, not even you.’

‘Well, why did you come here, then? And... how long are you staying?’

‘I head back tonight. I promised myself that I would never spend another night in this hole. When I was walking in this morning, the smell hit me, brought back so many memories. Some of them were good. Most of them, even. But that mouldy, damp smell also made me gag. The crazy thing is that it smells so much better than it used to! You remember how it was when we grew up. Before the doors opened, all that recycled air. Anyway.’ Esme stopped rambling for a moment. Tried to collect her thoughts.

‘So, what, you just came back for the day? What’s the point?’

‘Oh, Toyosi. You’re really going to make me spell it out?’

‘Spell what out?’ Toyosi was genuinely puzzled.

‘Ugh. You always did pick your moments to be completely obtuse! Well, here it is. I came back to get my measure of sand. Okay? Before I came to meet you, I spent the day finalizing the paperwork.’

‘I don’t believe it. Money. Money! You're here to get your money.’ Toyosi spat the words out with naked derision. ‘Seriously. What happened to you?’

‘Says the person who bought a barn owl to keep in a cave.’ Esme smiled triumphantly. ‘You think I didn’t hear about that? I’m not that far out of the loop. What is it your father used to say? Oh, yeah. “Nothing is wasted in the Colony, not even a grain of sand.” How do you think he would feel about Òwìwí?’

‘I used my measure of sand to honour my father. Òwìwí is for him.’

‘I never thought I would see you stoop as low as using your father’s memory as an excuse. Just so you can go on cowering under these artificial lights.’

‘Please stop mentioning my father unless you want to lose some teeth, bitch. And it's not all artificial light these days, is it? Surely you remember that much.’

‘And you think that little trickle of sunlight you get for an hour every day is enough? Ughhhh! Toyosi, you are frying my brain here. It’s like the blast doors in your head are still closed. You know, there are so many things that you can't learn from reading and watching videos. There was all this history happening outside the cave the whole time we were growing up. We... You think it's so great here. And I guess it was for us, growing up. We had nothing else. But, hello? The doors are open. It’s time to re-join the human race.’ A dog ran past them, with a seven-year-old holding its leash. It was not clear who was in charge of whom. ‘And another thing. I’ll have you know that money is the reason all these people are having babies.’ Esme’s voice was getting louder. ‘You barter and time-bank for electronic tokens. You exchange sand for goods and materials from outsiders. How is that any different to using money?’

‘In Colony One, no one is wealthy and no one is poor. That's the difference.’

‘You can’t possibly still believe that.’ Esme drew a loud breath as her eyes grew wide as two moons. ‘Kai! You actually do. Wake up, Toyosi! Please. We’re grown-ups now.’ They had reached Toyosi’s bungalow. ‘Oh. You’ve moved.’

‘Like you said. Things are changing.’

‘Look, Toyosi, this… all this. It isn’t what I really came here to say. I had it all worked out in my head and then… Well, anyway. Come with me. There are beaches out there where you can walk under the golden sun for days without meeting another person. After growing up in the Colony… all that open space? There’s nothing like it, I promise. The cities are amazing too. Some of the rebuilding work is just unbelievable. I’ve been to Lagos, Dakar. Addis Ababa, even. The pyramids in Giza survived. I’ve not been yet. We could go and see those together. We-’

‘Stop, Esme. Just stop. If we all do what you did, what happens to the Colony? Hmm? And anyway, don’t pretend you came back here for me. I already used up my measure of sand. So just take yours and go.’ Toyosi turned roughly and entered the house. It was the last time she saw Esme.

2139

The blast doors were opened on the first day of October. A few more probes were released, but really everyone could feel it as soon as the daylight hit them: it was safe to go outside. The first colonists left within days and were followed by dozens more over the next few years. Many of those people came back. Some just could not get used to the oppressive sky. Others could not stand the outsiders’ persistently wasteful ways even in a reduced, ravaged world. Still, every once in a while, someone new took their measure of sand and travelled out into the world.

Clean sand had already been pretty valuable when they began burrowing the cave. Along with soil, they had brought immense quantities of sand from all over the world. Silica sand for making glass; pit and crushed stone sand for all their construction needs; fine sand for water purification.

The asteroid impact of 2031 had covered large sections of the earth in a deep layer of sulphurous ash. The sand it created was dirty, poisonous and of little use without considerable effort. The purity of Colony One’s sand was like a connection to a vanished world and the outsiders lusted after it. In particular, the outsiders wanted it for their communication devices. Too long had they been repurposing screens from the devices that survived. They wanted to make new things. In this way Colony One became very prosperous. Each colonist was entitled to a share of this sand wealth, and if they left they could take a share of the sand itself. Those who stayed in the cave had their own reaction to the doors opening: they procreated.

In the beginning, balance was paramount in Colony One. Just as there had been strict rules about childbearing, the decision was made that pets would not be allowed. The mental health benefits they afforded were outweighed by the food and oxygen each extra animal would require. The only animals in Colony One were livestock. After four generations, the colonists desired pets with an intensity that matched the outsiders’ desire for sand.

Many dogs and cats had survived in the bunkers, basements and purpose-built facilities where their human owners had successfully sheltered. Reptiles and rodents were not uncommon, too. The rarest of all were birds: extinct on the earth’s surface and exceedingly difficult to keep in enclosed spaces. Some of Toyosi’s happiest memories from her teens involved getting her father talking about birds. He talked and she listened, for the most part, but that was just fine.

The day Toyosi secured the barter for Òwìwí on a video call with the researchers at Porton Down in Salisbury was one of the happiest of her life. When the military plane arrived to deliver the adolescent owl, Toyosi smiled so hard and for so long that the next day her cheeks ached.

2155

Toyosi arrived on a rock ledge in time to see the first glimmers seeping into the cave, gradually turning the air golden. Later, as the light crept away, she would turn around and watch it go. Sunrise and sunset in just over an hour. She recited the catechism quietly to herself, bathed in those numinous rays.

This is a benevolent universe.

There is no need to fear.

There is no Devil.

I deserve to be joyful, successful and loved.

Character determines outcome.

Supremacy is evil.

I must never harm another human being.

I must never harm the universe, of which I am a part.

As children she and her classmates would repeat these words every morning, standing up with hands over hearts. Toyosi felt closer to her father when she spoke them. He had tried to live by those words. Eventually they got him killed.

Back when the blast doors were still closed, a millennial cult had swept through the Colony. A doctor named Elizabeth Kamara believed that the asteroid impact had turned the world outside into a paradise. To her it was obvious that the blast doors were being kept shut to hide this fact and keep the colonists under control. Her medical training gave her credibility and at her peak she counted one in every three colonists as a believer.

The Kamarites grew in anger each time the doctor's claims were debunked, dismissed repeatedly by probe engineers and the Colony Council. Eventually, inevitably, the Kamarites turned to violence, attacking council members at their homes and planting credible bomb and arson threats in official buildings. The Probe Department was a particular target, but Appiah resolved to continue going to work. He believed in a benevolent universe. Eventually the Kamarites made good on one of their threats and Appiah died trying to save probe equipment from the flames.

Toyosi’s seizures became much worse after that. They came more often with increasingly vivid hallucinations. Epilepsy was not a specialty for any of the doctors in the Colony, but they managed it as best they could with cognitive behavioural therapy and their limited supply of anticonvulsant drugs.

Stood now on an outcropping, Toyosi watched the colonists milling around under ochre sunlight. She saw construction workers breaking for lunch on a new computer centre and more children than ever sending up all manner of noise from their playgrounds. She looked up and saw Òwìwí’s nesting box. This perch was his territory, but the bird did not see Toyosi as competition. In fact, to his mind, Toyosi was his mate.

The buildings and spaces mingled with the people from this vantage point. How could anyone want to escape this place? A broad smile of satisfaction spread across Toyosi’s face and for a few moments the swirling waters of her mind lay calm. And then she felt her ears pop.

The light changed like a switch had been flipped. Toyosi was used to the artificial light of the cave but this was different. Cold, almost grey light that cast no shadows and seemed to radiate evenly throughout the space. The cries from the children could no longer be heard. The cave was now totally, horrifyingly silent. Toyosi looked down and saw a stone on the ground in front of her. There was something written on it. She picked it up, taking a moment to feel its weight. It was much heavier than she had been expecting. The stone was about the size of her palm and in its centre was a single, simple word:

NO!

Without really thinking, Toyosi pressed her finger to the stone, right into the space between N and O. The word was actually a button, and she immediately wished she had not pressed it. Dark grey smoke began fizzing out of the stone at an incredible rate. Involuntarily she flung the stone from her hands and it fell off the end of the outcropping. It fell towards the Colony. Smoke began rising up from many points all over the cave. I must never harm another human being. I must never harm the universe of which I am a part.

The Colony was just a grey mass of smoke now. Toyosi tried to call out, to warn the colonists somehow, but the words stuck in her throat and she gasped like a thirsty person as she tried to get them out. Before long there was now just a grey mass of smoke where the Colony had been. She looked away in horror and saw her father standing impossibly on another outcropping. He was perfectly still. Over six feet tall, broad shouldered and comfortably chubby. He was wrapped in the same red tunic he had been wearing on that last morning. His face bore the smile that had been the first light of Toyosi’s life.

Baba! Baba!

The sound of her voice brought him to life.

Toyosi, what's happening? I'm going to come to you! Stay there!

He moved down quickly from his outcropping and was soon beyond her line of sight, obscured by smoke once again.

Baba! NO!

Òwìwí flew into Toyosi's line of vision, seeming to pass by her in slow motion. Six wings and then eight and then ten as each frame of his movement was held a few moments longer than normal. The owl’s serrated feathers stuck out in razor sharp contrast and seemed to slice through the air. Òwìwí was spotted all over and these white spots left their own trails as the bird silently beat his greyish brown wings. The eyes in his inscrutable heart-shaped face were obscured by angular slits of fur above the beak. Shimmering electronic music played: a bassy synthesizer trumpet paired with a high arpeggio picking out the notes of an uplifting major chord. The kind of music you would hear as the doors of heaven opened to you after a long lifetime of work. Was that sand she felt beneath her feet?

With a jolt of her head the music stopped. Toyosi could hear the children and construction workers again. The hour of daylight had passed. She was lying on her back with Baba standing over her. No… not Baba. Esme! She was talking but the voice was muffled. Hang on, no, not Esme. Mama!

‘Who are you?’ Her mother’s voice calm and grainy.

‘That’s kind of a heavy question, Mama. A cave-dweller. A cave-imprinted human. A lovesick architect. No. Structural planner. Y’know… engineer. I mean… who are you?’ Words were pouring out of Toyosi without much control.

‘Haba. This seizure was a bad one o. I heard you screaming all the way from my house.’

‘I’m just fooling around, Mama. No, not fooling around. Not with you. Playing around. Having a laugh. Yanking your chain. I’m Toyosi, of course.’

‘Okay, and where are you?’

‘Where else would I be? The cave. Here I stand and here I’ll stay. Except I’m not standing right now. Help me up?’ Toyosi tried to lift her head but the world turned to liquid before her eyes. ‘Yeah, maybe I’ll just lay here for a while. Work can wait.’

‘Okay, last one, my dear. What year is this?’

‘I’m not even going to answer that, Mama. I’m fine! Really.’

‘Toyosi, please. You know I have to run through the- Haba!’ Her mother ducked as Òwìwí swooped down at her, barely missing with her gleaming talons. ‘That damn bird! Will you-’ She had to duck again as the bird made another pass. Toyosi could not help but be amused and her uproarious laughter mingled with the Òwìwí’s metallic screeching.

Eventually her mother helped Toyosi up and together they walked away from the cave mouth and towards the Colony. Artificial sunlight warmed them all the way.

About the Creator

Olugbenga Adelekan

Bass guitar and words since '82.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.