Nature as Inner Archive

Where memory is bark-deep, and the wind still whispers what we’ve forgotten.

I’ve always believed that forests remember.

Not the way people do—with names and faces and misfiled photographs—but in root systems, in sun patterns, in the particular rustle of leaves on certain days of the year.

After my father died, I stopped speaking for a while. Not in the dramatic way people write about in memoirs, but quietly. A shrinking. Words curled inward. I wasn’t even sure if I’d noticed it, or if the world had just grown louder in comparison.

But the trees noticed.

It began in late spring, three months after the funeral. I started walking in the woods behind our house—where the birches grew in a lazy arc and the moss was thick enough to lie on. It was the only place that didn’t tell me to move on.

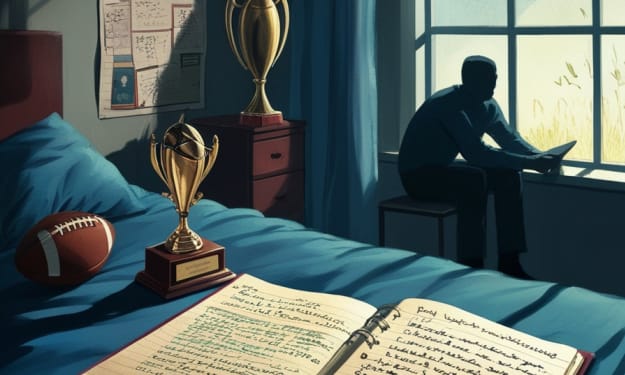

I brought a notebook, of course. I didn’t speak, but I wrote. Poems. Fragments. Little prayers with no recipients.

One day, I wrote:

“Grief is not loud. It hums.”

I tucked it into a hollow of a tree, without thinking.

The next day, there was a pinecone where the note had been. A perfect one, still fragrant.

Coincidence, I told myself.

But I kept writing. And the forest kept answering.

A note about dreams, and I’d find a feather.

A poem about silence, and the next morning—birdsong.

A line about drowning, and suddenly—dew, everywhere, like the woods were weeping for me.

It was never more than small gestures, but it felt like dialogue.

Like the trees were keeping a file on my sorrow.

I named them, sometimes. Not with real names, but with feelings.

The tall spruce near the creek was “The One That Listens.”

The twisted willow was “The One That Remembers.”

They all had personalities—root-deep wisdom, ancient indifference, occasional mischief. I began to trust them more than people.

One afternoon, late July, I found a page of my notebook wedged into a tree I didn’t remember visiting. The handwriting was not mine. It said:

“You are not broken. You are composting.”

I laughed. For the first time in weeks.

Somewhere, something had started to heal.

When school resumed in the fall, I spoke again. Slowly. Cautiously. Like someone relearning how to walk. My friends noticed, but didn’t push.

They thought I’d just “gotten better.”

But I knew better.

I hadn’t healed by moving on—I’d rooted myself somewhere older, quieter, deeper.

Years passed. I left home. Cities swallowed me. I learned to function in noise, to trade wildness for wifi, to speak like nothing had ever fallen apart inside me.

But I always found my way to green.

A city park. A rooftop garden. A pothole full of weeds.

Nature became my library.

Not just a place of escape—but remembrance.

I began teaching environmental literature. On the first day of every class, I ask my students to bring something natural that holds a memory. A rock from a first hike. A leaf that looks like a childhood drawing. A photograph of a grandmother’s garden.

Then I say:

“Nature is not outside you. It is you.

You’re not just remembering through it—

you’re being remembered.”

One fall, I returned home. My mother had kept the house mostly the same—except the woods behind it had grown denser. Wilder. Almost protective.

I went walking again, following the same old paths.

And there it was.

My tree.

The one where I had left the first poem.

Now thick with age, bark like cracked language.

And tucked inside a crevice was a note. My own handwriting, yellowed and weather-worn:

“Grief is not loud. It hums.”

I hadn’t written it for a decade.

Yet the forest had kept it.

I stood there for a long time. Listening.

To wind.

To birdsong.

To the hush of something larger than memory.

And I thought:

Maybe we don’t lose parts of ourselves after all.

Maybe we just leave them behind in places that are better at remembering.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.