A HAPPY STORY ABOUT THE UNIVERSE, AND STUFF.

If the universe had never existed we’d have had to invent it.

First there is something, then there is nothing.

No wait, that’s reversed.

Or is it?

So many ways the universe can begin. It can explode into being from nothingalmostnothingImean, or it can be born on the back of a crocodile, the way I think I read once that some cultures believe the universe was born: the crocodile had to carry a frog across a river, I think, and there was a fox too, or maybe a hippo? The details may or may not be unimportant. It is hard to tell, for true stories.

This is a true story.

This.

It’s not true in the sense that you are thinking like oh “It’s true that I got up this morning and I brushed my teeth and then I saw that I was on a train traveling through I bet it’s the English countryside only it doesn’t make sense that there are crocodiles there,” even though much of that sentence is true, for instance:

⦁ I did get up this morning. (Sometimes I don’t).

⦁ I did brush my teeth.

⦁ It doesn’t make sense that there are crocodiles in the English countryside.

The crocodiles are only there in my imagination, but so many things are only there in our imagination that sometimes you just have to take things on faith, right?

Take Mount Everest. On faith. You ever been there? Me, neither. But we know it’s true, right?

First there is nothing, then there is something.

That is how universes start.

That is, essentially, how everything starts.

Let me tell you how the universe started.

Not necessarily this one.

Just one of them.

First there was nothing, then there was something.

That is how the universe started.

What?

Well, the details.

The details.

Are they important? Maybe, maybe not.

I have been on a train only once before in my life, once before this day when I am on the train again, the train with the crocodiles and the England and the guy next to me that I’m talking to and, you understand, some of this is real and some of this is not and some of this was real but maybe now is not.

Every story is a creation story: every story is about how something was once nothing and nothing was someday something.

In every story we take things we knew once and saw once and thought once and put them

Here

Here

Here

Way over here

(and in between)

And we brush them over with paint and we polish them up and we twist them so the right side of the tree – the proper side, the one where the nice ornaments will go, the side without the gap between the branches where Dad couldn’t fix it with the thin green wire he keeps on his workbench in the messy unfinished part of the basement just for this purpose – we twist them so the proper side of the tree faces the room and the gap is hidden (but still there, something that is also nothing, for what is a gap but a hole, a nothing?).

Every story is a creation story and so this story of me on the train and the guy and the crocodiles is a true story that I am creating about creation.

First there are maybe one thing, and then there are lots.

That’s another way to create a universe.

Here’s a third:

One day, two ant colonies went to war. I don’t know why people write war stories. It seems like if you’re going to create a universe you’d create a universe where nobody went to war, where nobody had to stand in a trench until poisonous gas swept over them and they choked to death drowning in their own lungs or planes went overhead and dropped down containers full of light so fierce that when it leaps out of its cylinder, it sends a shockwave ahead of it, light so powerful that it pushes actual physical substance away, did you know light could do that

(it can)

And then burns away the flesh and leaves only a silhouette of what the person was, against one of the walls it could not knock down? Did you know light could do that?

(Id.)

But here I am writing a war story, which is a creation story, and these two armies of ants went to war: two colonies fighting over what everyone always fights over: nothing and everything: everything because they are fighting for survival, which is literally everything, and nothing because really there’s more than enough survival to go around. We just never believe that.

We just never believe that because you know what? We keep running out of survival at the very worst times, the very worst times being when we are not ready.

Like 4:37 p.m. on a Tuesday afternoon. Who’s ready then to maybe be told they need some more survival and hope the store is open so they can get some, quick?

The ants: they went to war, and the fighting was fierce. Probably about a billion ants went frothing over everything between their two anthills which seemed like two different worlds, separated by vast distances to these tiny, silly ants who thought they knew how the universe looked but they only saw it from their perspective, and the anthills were, like, five yards apart, plus there weren’t really a billion ants, it just looked like that. They went to war and it was fierce! I might as well tell how it was because you’ll imagine it anyway, and how can it be worse if I tell it then if you think it?

The ants were ripping each other apart, their pincer-teeth or whatever grabbing antennas and legs and thoraxes or thoraxi or however you want to say it, and they were rolling around and cut in half and it was Carnage!

CARNAGE!!!

But one ant saw that, he was at the back of the line of ants waiting for his chance to tear something off of someone, that was his job in the war, and he looked up as he waited to reach the front lines, and he saw up in the tree a butterfly sitting on a branch, lazily waving its wings back and forth.

The ant had some time – this all happened pretty quick but ants only live a day or something so a minute to them is like 3.7 years to us, if you do the math, which I didn’t – and he watched the butterfly and he saw a ray of light

(not the bad kind that burns and knocks things down, the good kind that makes you think maybe you want to take your kids to the beach even though it’s only May)

The light hit the butterfly (hit is a strong word; let’s say caressed) caressed the butterfly and the ant saw the butterfly’s wings glow even brighter and the ant thought

That is the life for me.

It tried to talk to the ant next to it, tugging its buddy’s antenna and trying to get its attention but the buddy was too focused on just what part of what ant it might grab and rip off, greater glory for that ant’s pile of dirt and all, and so it ignored the ant, who realized that he could just leave the line and go to that tree.

So it did that.

It left the line of ants waiting to killorbekilled and it walked as quickly as it could, to the tree trunk. This was new territory for the ant because usually it just went where its pheromone trails told it to go:

Food nest water tunnel

Whatever it is ants tell each other with smells, I mean.

But here there was no trail: the ant had to think what it was going to do, how it was going to get there and it had to invent a way to do that because nobody had thought to ever map out for the ant how it could get up to the branch by the butterfly.

The ant told himself a story, is what he did: he told himself a story about an ant, like him, who walked out of the line of ants waiting to killorbekilled, dieorlive, and walked over to a tree and found a way to climb the tree and then go out and sit next to the butterfly in the sun. And the story was true.

The ant was on the branch, I mean: he was there, and you may say “Well, was he really truly there? Or did he just imagine that?”

And I will say: to an ant waiting in the line of ants ready to rip each other apart, does it matter?

But yes, he was really there.

And he and the butterfly sat quietly in the sunlight, far far above the war below, far away from all the dying, and the ant saw that he could look down at the carnage or he could look up at the sun, and when he looked up at the sun he saw streaming light down through the clouds hitting trees and ferns and rivers and lakes and beaches and parrots and peacocks and lots of other beautiful stuff, maybe paintings by Da Vinci or something.

Then the butterfly flew off into that expanse, its wings flapping in that crazy happy way butterfly wings do. They never fly straight, do they? Butterflies are crazy. I bet they really are.

The ant had known things could fly of course: birds sometimes ate ants and there were flying bugs they saw and so things can fly, the ant knew but before just that moment the ant had never wondered if he could fly, and so the ant told himself another story and it was a short one:

Once,

he said to himself (he spoke ant so I'm translating)

there was an ant who could fly.

And so he flew.

And again I hear you: Well, did he really fly?

All stories are true.

Like this one time at 4:37 p.m. on a Tuesday afternoon where I kept telling myself a story.

It’s probably nothing, was the story I told myself.

All stories are true.

SO YEAH THE ANT FLEW OKAY?

He flew off into the distance, flying kind of like a butterfly would because that’s how the ant wanted to fly, so he added that in to his story and he flew all over the jungle past the parrots and the Da Vincis and whatnot, and while it was pretty great, the ant had to admit that there were still some bad things like the fact that there was still the war going on and he knew that his ant brethren were killingbeingkilled and he assumed that lots of other things were going on like that all over the place, too, and you know it doesn’t seem right, does it, that there’s so much good in the world and yet it’s spread out unevenly and so ants and parrots and people who would rather be flying or cawing or riding trains through an English countryside filled with crocodiles have to instead do things like go to war or not caw or sit at their kitchen table and listen to a phone call explaining nothing?

So the ant told another story:

Once upon a time, he said,

There was another universe that didn’t have all those bad things.

And nobody ever saw that ant again.

In this universe, anyway.

There was another universe that didn’t have all those bad things.

I mean, why not make that this universe?

“I see your point,” says the guy next to me on the train,, handing me some of his marmalade and biscuits. “It seems like a terrible design flaw on the part of whoever created the universe, doesn’t it?”

I nod, and I take a biscuit and dip it in marmalade or spread some on or whatever. The devil is in the details. There is no devil in this story.

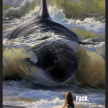

We look out the window at the crocodiles for a moment.

“I’m sorry, who did you say you are, again?” the guy asks me.

“I’m me,” I say.

“And you are,” I say, after a moment.

“I’m God,” he says. “The guy who runs this place.”

First there was something, then there were more somethings?

I thought I read somewhere that if God didn’t exist we’d have had to invent him. Or maybe that was Evel Knievel.

But don’t we mostly invent God anyway? Whether or not he exists, we invent him the way we invent Mount Everest, and English Countryside Crocodiles. We’ve never seen him. We have these things around that say he is probably here – I mean, the universe, e.g., -- but that’s all.

If there was nothing and then something, where did the something come from?

But if there was something and then something, where did the first something come from?

If the universe had never existed we’d have had to invent it.

Here is another story about how the universe was created.

There were, say, 10 angels. They were all hanging around doing nothing much and then one of them said “We should create a universe.”

“Why?” said one of the others, it doesn’t matter who. He was the kind of angel who would say that, just to be provocative.

“Why not?” said the first angel.

“That’s not a really good reason to bring into creation everything that ever has or will or could exist,” the second angel correctly pointed out.

“Well, what’s the counterargument?” said the first.

The other angels more or less just watched and listened.

Except this one who said “It would be nice if there were sunrises.”

They all kind of agreed that yeah, sunrises are pretty cool and they could use some. So they made some. They bickered for a while about the exact amount of purple to put in and when they should happen, these sunrises, and whether they should take a long time and all that but eventually they came to terms on how this would all work and there were sunrises and they enjoyed them a great deal.

That kind of got the ball rolling and they decided to make some other stuff but as they began kicking around ideas the second angel, the nit picky one (who probably would have made a great engineer if they’d created those yet) pointed out that they needed a place to put this all, so they all decided to separate heaven and earth and make some space and then they wanted to make sure everything happened in the right order and they got together and came up with time and then they really went crazy, making all sorts of imaginable things (you thought maybe I’d say unimaginable but nothing is unimaginable, really, not if you understand how imagination works) until they had filled this universe with stars and parrots and Da Vincis and people and planets and corn dogs and stuff, and it was a mess, everything was just chaos, I mean volcanoes and comets and lions living in Manhattan and whatnot.

The angels got back together, and decided that this really needed to have been better planned.

They talked about just scratching it all and starting over from the beginning, keeping maybe sunrises and a few of those neutrinos plus pecan pie, maybe, because that was delicious, but to do all that seemed like a lot of work, so instead, they created God.

“You,” they said, showing him the entire universe from the edge of the cloud they were all standing on (for dramatic effect), “get ALL THIS.”

God immediately resigned. I mean, you cannot imagine the chaos. Well, you can, vis a vis, my earlier point about imagination, but I was speaking for hyperbolic effect. So you can imagine it but you’d better really work that ol’ imaginer, there.

“You can’t resign,” the angels told him.

“We made you to take the blame.”

“So, what do you do, God?” I ask the guy on the train.

“A little of this, a little of that,” God says back. “A lot of math, actually.”

“Really?” I say. “Math?”

“Yeah… math is really important. If you want to get things right, that is. You can’t just half-ass it.”

I tell him about how in every math class at some point, someone, probably me a lot, says “When am I ever going to use this?”

“What did your teacher say?” God asks.

“He said stuff like its useful for a lot of things, including just generally learning to think logically.”

God eats a biscuit which remember for this story is a cookie. Or maybe a cracker? I forget. Anyway, he eats one, wipes some marmalade off his moustache (God doesn’t have a beard, sorry, that’s wrong if you think he does, he doesn’t, just the moustache, a cool one) and says “He should say that math is important if you don’t want every goddam planet spinning into every other planet, or if you’re interested in not having people and crocodiles and ants flying off into space because you got gravity wrong, or if you’d like to maybe not have suns going supernova at random intervals. He should say that math is important if you don’t want things to fall apart instantaneously.”

We sit quietly for a second, me wishing I’d paid a little better attention in algebra because honestly I feel a bit guilty at that point.

“Anyway, I’m working on it,” God says.

First there are lots and lots and lots of nothings.

Then there is something or somethings and you realize that all those nothings weren’t nothings at all.

You didn’t treat them as nothings: they were pizza parties and long drives at night with music playing and going for a jog in the woods or driving fire trucks on the living room floor or cooking Thanksgiving dinner or going to a museum or getting married or going to sleep at night with your hand lightly resting on the shoulder of your wife who was already snoring pretty loud but you let her sleep because she’s had a long day so you don’t even nudge her to roll over. They weren’t nothing not really but they were in the past and while you enjoyed them they were nothing anymore, just pictures or leftovers or memories, and a memory isn’t anything other than a story, too – I have a story about Mount Everest and a memory of Mount Atlas in Africa and the only difference between them now is that I actually stood on Mount Atlas, but they both have the same heft in my mind – and so they were fading away, confabulating, mixing and matching into new stories about the past and the future but they were also nothings.

Why? Because we had so many of them. Think about this math:

When you celebrate your first Christmas, that is probably the first of 70 or so.

When you see your first sunrise, that might be the first of 25,550 you could see in your life!

When your heart beats the first time ever it does, it’s 1 down, maybe as many as 2,227,520,000 to go.

That is a lot of nothings to pile up, a lot of moonlight walks and raking leaves and Christmas parties, and when you have 2,227,520,000 things to go you can kind of let some of them slide.

But then one day you get reminded not just that there is a finite limit to these things, but that the finish line in your case might be in sight. One day you get a phone call and the scientist on the other end -- the scientist of men, he's a doctor -- is telling you things that don't make sense and the specific way that they don't make sense is that they may or may not mean that the finite limit to things may or may not be in sight of you. He is telling you that soon you may, or may not, be.

That causes a different kind of math: A balancing.

Is this more important than that?

Is this something I should be doing?

Should I worry about next week?

Next month?

Next year?

What’s going to weigh more, at the end: never seeing Mount Everest? Or never following through on your promise to take the boys back to the pool with the dolphin slide?

“God?” I ask.

Outside, the crocodiles are smiling.

“Yes?” he says, looking up from his Sudoku.

“Just checking,” I tell him.

Later, we thumb-wrestle.

Here is one more story about how the universe was created:

Once upon a time, a man was born and a woman was born. Maybe they were made, maybe they were born. It was the same thing, really, no matter how you look at it. Nobody is born unless they were made, too, regardless of how you think the making was done, by magic or by biology (because they are not different and if you say they are different then explain how) but whatever, they were made.

And they made a man and a woman, and they made a man and a woman and they made a man and a woman and they made a man and a woman.

This went on for days weeks months years decades centuries millennia. These men and these women began to walk and make wheels and make fire and cook animals and grow crops, and build houses instead of living in caves and then they built bigger houses and then they built boats and found other places to walk and build houses, and they ran into other people who had been doing the same thing only on their part of the world and sometimes they were friends (mostly they were friends) but sometimes they were not, but through it all they kept on making more men and women and men and women and men and women and they made other stuff, too. They made cars and trains and buildings that you couldn’t even see the top of from the ground sometimes. They canoed and rode and drove and trained and then flew like birds, and then flew like gods, rocket-propelled past the air that they had always lived in. They walked on other worlds, and they looked back at the tiny place they had come from, this world that had taken them millennia just to walk around and yet here they could just block it out with their thumb.

They didn’t stop there. These men and women made more men and women and more men and women and more men and women and they kept on pushing farther and farther and higher and higher. They didn’t stop at just one world, they wanted to walk on them all. There was something about all that stuff out there, all those rivers and oceans and mountains and skyscrapers and then moons and then gas planets and rings made of rock and icy comets and neutron stars hard like ping-pong balls glowing with fierce energy, something about clouds of dust bigger than galaxies, something about vast reaches of space pockmarked with tiny holes that held it all together, something about all that, that made these men and women and men and women and men and women keep telling themselves this story over and over and over:

Go on,

their story went.

Somewhere in there is me.

Go on.

And that story, too, is true.

About the Creator

Briane Pagel

Author of "Codes" and the upcoming "Translated from the original Shark: A Year Of Stories", both from Golden Fleece Press.

"Life With Unicorns" is about my two youngest children, who have autism.

Find my serial story "Super/Heroic" on Vella.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.