The first time I tried to move to Canada, I chose the day wrong. April 22, 2020 was when all direct flights from India to Canada were banned.

I was at the New Delhi airport, all ready to board and start a new life when the news came.

Almost immediately, most of the Air Canada counters were closed. I stood in the queue to reach the only two open counters. Two helpless ladies were explaining to passengers who were irate, frustrated, and despondent, or shuttling between these emotions. Big hulking men looked close to tears. Ladies were sobbing or shouting, “How can you stop the flight? I have tickets!”

Older kids looked worried because their parents were worried. The younger ones played. They did not understand what the commotion was about and mostly, did not care.

After 15 minutes, I realized that there was no way I could reach the counter. And it did not matter too. If the government had banned the flights, there was nothing the airlines could do.

After 30 minutes, it seemed the airlines could do something. Some passengers were being allowed through the gate. I waited. Praying.

I reached the counter after one hour more.

The lady in the counter was sympathetic. She looked up all my documents. With each rustle of paper as she went on the next document, my hopes rose. I had heard murmurs that there was an indirect route through the US. From New Delhi to Newark. Just a few hours at Newark and off again to Montreal. It was Air Canada collaboration with United Airlines, and the passengers checking-in were being offered that flight. They paid the difference of the fare between their ticket and the indirect ticket. I was praying I had enough money to pay for it.

“I am sorry, sir,” the lady began, and my heart sank when I heard the sorry. “You do not have an US visa”.

“Of course, I do not have an US visa,” I said a little forcefully than I intended. “I am going to Canada.”

“I understand, sir. But you need an US transit visa at least to travel on this flight.”

There was finality in the lady’s voice and she looked beyond me to the next person. But I was not moving out.

“OK. Where can I file for an US transit visa,” I asked. “I don’t suppose I can get it tonight but what about later? Can you book me on the same flight tomorrow? I will pay the difference in fare.”

The lady looked back at me.

“You cannot get an US visa, sir,” she said with finality again. “Not overnight. Certainly not with the pandemic on.”

It almost seemed that she wanted to tell me that I could not get an US visa even without the pandemic, but she stopped short. She looked at the next person in the queue again.

“I am going to have to ask you to move now,” she said.

Behind her the airport guard made a slight but perceptible movement as if to indicate my time at the counter had run out.

I stood undecided. I wanted to plead with the airlines to please take me. But I knew it would not make a difference. I moved out of the queue, ashen faced. Dejected.

The night was not over.

If you get into international section of an Indian airport and could not board your flight, you need to pass through security again to get out. You could not pass through security on your own too. The airline had to send an employee to go with you and lead you out. Air Canada was busy trying to get people on the indirect flight or trying to mollify those that they could not. Most passengers explained a lot, then pled, and finally cursed.

I sat a little way from the queue. Waiting for the promised airline employee who would enable my passage out of the airport. I had nowhere to go in Delhi. I had left my hotel room. Converted all my Indian currency into dollars. Left my pet owl with my friend who promised to care for her.

I sat. Waiting.

I must have fallen asleep. Maybe I was dreaming that I was on my flight.

The airline employee tapped me on my shoulder. I woke up with a start ahd found myself still at the airport. Looked at my watch. Almost 4 hours had passed. It was almost morning.

“Sir, you have to come with me,” the airline employee said. He was not very polite. But he got me through security and out of the airport.

I took the flight back to Bangalore next day. I no longer had a job there, but Delhi was too expensive. I had a friend in Bangalore.

On the day I was back, I was in for another shock. My owl, Hedwig (named after the one from Harry Potter) had flown away. My friend Ramesh was very sad and apologetic, but there was nothing to do. The owl could not be found.

I spoke at home and told them of my missing owl. My mother was not interested. She wanted me in Canada, so that she could travel too. I agreed that Tigray had become too unstable and the war was not going well, but my primary concern was Hedwig.

I spent days trying to look for her. There is a way to look for an owl. They are too well disguised to spot amongst trees or even buildings. So you wait for them to be mobbed. By mobbed, I mean, when other smaller birds, mostly crows and sometimes sparrows, group together and hound the owl from their territory. I always found it fascinating. Tiny birds chasing a huge bird of prey. Often, successfully.

I did not know why the owl fled. Maybe it was well mannered. Hedwig was. Maybe the effort expended in going after the mobbing birds was not worth it. I knew owls fought back when they defended their nests. Not otherwise. Crows and sparrows were also intelligent. They never pressed owls close to their nests. It possibly had not ended well for them previously. They remembered the lesson learnt over generations. Birds are intelligent that way. Humans forget.

Humans also have lost the decency of the animal world. They mob people near and away from their homes. As I thought about this, I noticed a small crowd gathering. I had been looking for Hedwig today and had entered an area I should not have. A wedding was on, and by looks of it, I was unwelcome near it.

The doormen or guards, I could not tell which, started to make towards me. I waved and retreated. I was an owl away from home. I let the mobbing birds win.

I did not find Hedwig. Everyday Ramesh was apologetic. Apologetic to the extent that it had become slightly irritating. I found a job in a call center. It was below my training as an engineer, but was only thing available.

It catered to an animal helpline. I was hopeful that Hedwig had not flown out to the forests, and would eventually make her nest in someone's home. In India, unlike many other places of the world, owls are worshipped as being related to the goddess of good fortune. They are not killed. So, if ever, someone found Hedwig and was afraid, I will be contacted. Or maybe someone else in my office will. I had told everyone about my owl. They thought it was an odd pursuit amidst the pandemic where families were the primary concern and people, indeed, were dying. However, they agreed to inform me about any owls they came across.

Over the past four months, I had been with the team for 3 house visits. We rescued 2 owls, one had been dead. But it was not Hedwig.

Neither were the rescued ones. One of the birds we rescued was actually a kite. Not an owl. People had wrongly identified it!

Situation at my home had turned even more dire. I had trouble speaking to my mother. The network was poor, and she mostly sobbed. People I knew were dying in Ethiopia too. But the virus had no role in it. Humanity, often, is worse than viruses could ever be.

I concentrated on Hedwig. As the pandemic situation turned worse, lockdowns were clamped on. I missed out on visiting the next two rescued owls. But the team kindly shared photos.

Not Hedwig.

It was difficult to send photos from Tigray, Ethiopia. The internet had been locked down.

But I spoke to my mother again. She sobbed. But she was OK, she said.

She wanted me to go to Canada. It was her ticket out of the war.

I had almost given up on Canada due to my focus on Hedwig. My mother was also important.

My uncle was taken prisoner in the war. My mom openly cried on the next call. I did not like it when she sobbed. I hated it when she cried. I felt helpless.

My uncle had been distant to us when I was growing up. He came infrequently. I had very faint memories of him and not that good memories too. He had a habit of flying into rages. I had been afraid of him.

"Solomon," he would call out in his big booming voice, and I would cower behind my mother.

When I heard he had been taken prisoner, I tried to recall if I remembered his face. I did. But vaguely. Like Hedwig. I was afraid I could not recognise her when I met her or maybe she won't recognise me. Owls had good memory. But for human faces? I did not know.

I felt a foreboding for my uncle, which was strangely similar to what I felt for Hedwig. When I had reached the house where the owl had died, I was reluctant at first. But I forced myself to look in. It was not Hedwig. I was relieved. But I knew it could have been Hedwig. It was the same for my uncle. It felt helpless knowing that the next home with the dead bird or the next call from my home could relate news about her or him.

I started looking for options to fly to Canada again. Indirect flights because all direct flights were cancelled. I contacted my Indian friends, who contacted their Indian friends, who contacted theirs, and so on. Indians are very well connected. And resourceful. And intelligent. And too numerous. Flight bans did not stop them. They were flying to Canada through Serbia, Mexico, Turkey and, indeed, Ethiopia.

I collated my funds. I did not have much left. 5 months without a proper job had seen to it. I wondered how much food stash Hedwig had accumulated. Possibly, she was richer than I was.

My travel agent told me I could not go through Serbia and Mexico. It was too expensive. Turkey (I always wanted to see Istanbul) was possible, but they sometimes failed people on RTPCR. If they did, I would have to stay there for longer and I did not have the money for it. Their laws were also changing daily. In summary, it was risky travelling through Turkey.

"Why don't you go through Ethiopia," his employee at the reception asked the question I had been dreading. "It is the cheapest and safest for you. You are from Africa, right?"

I was from Ethiopia, but to many Indians, Africa was one big single country.

My travel agent Bijay was not one of those Indians. He knew and remembered I was from Ethiopia. He was just a bit surprised I did not suggest Ethiopia on my own.

"Solomon is from Ethiopia," he told his employee who shrugged and smiled as if she had made all my problems disappear.

"You do not want to go through Ethiopia, Solomon," asked my travel agent Bijay. "Don't worry. The war is happening to the north. Addis airport is open and functional."

Of course! The war was in the north. I knew the situation in my own country. I had daily reports from the ground amidst the sobbing from my mother.

"Yes, I know," I replied. "But, the situation may deteriorate. I would like to pursue travel through Istanbul."

Bijay's employee looked aghast.

"But Turkey is expensi-," she began.

"We will see what we can do," Bijay cut her off.

I nodded curtly. "Thank you."

I mailed my Canadian employers that I was looking for an indirect flight to Montreal. They wrote back saying they would arrange my stay.

Things were coming together. If I was to find Hedwig or the war was to end, it will be alright finally.

Next morning, things started coming apart. I had not found Hedwig. The war was worse.

And, Bijay called.

"Turkey closed its direct flights to India, he informed. "You can still fly to Canada from Turkey, but how would you get to Turkey?"

"So flight through Addis Ababa is the only option on the table," I asked knowing the answer.

"Yes."

"OK. Send me ticket details and cost."

My mother called that evening and did not like my plan.

"You should not fly through Addis," she said. "They will arrest you."

"But why, mother," I asked. "I am not in army. I am not a threat. I am a nobody."

"You are flying in from a foreign land and flying out to a foreign land," she continued. "You are not a nobody. You are fortunate. People do not like good fortune here these days."

I still had not found Hedwig, so I did not believe I was fortunate.

Maybe I was. Few people had read of Hedwig in Ethiopia. They saw the Harry Potter films, but many had not read the books. I even knew of the fictional Hedwig Robinson and how she escaped East Germany. Fewer people knew of her. Fewer still would be accepting of her.

So who was Hedwig named after? Both the owl and the person. Each inspired me in their own way. So, yes I was fortunate. Few people found inspiration.

"-cannot come. Should not come back. Go some other way," my mother kept repeating on the phone.

"OK, Ma," I agreed because it was futile to debate. "I will go through Turkey."

"But you said that way is closed."

"I will fly through another country from India to Turkey. There are flights through Qatar. You remember Qatar? Cousin Yohannes works there."

"Yohannes who cooks," she asked.

"Yes."

"OK. Go through there. It is safe, his mother says. They have a big stadium. Even we have a big stadium now in Addis. But it is not complete."

My mother had drifted off into how the stadium should have been complete by now but was not. It meant she was reassured. I waited for her tirade to end, assured her again that I will fly through Turkey and asked her to stay safe.

I booked my tickets through Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Hedwig was still nowhere to be found.

There were less frequent calls on owls this month. But I overworked at the call center. Hoping.

My final day in India had arrived. I had not found Hedwig. Nor had I informed my mother of my real flight plan. She knew I was flying through Turkey.

I will tell her when I reach Canada, I thought.

Ramesh came to drop me off. We had just started in his car for the Bangalore airport, when my friend from the call center called.

"Solomon, we have found your owl" he said solemnly.

I was taken aback for a moment by his voice. I feared the worst.

"Where did-," I managed. My voice must have sounded odd because Ramesh looked at me concerned.

"I am sending you the photo," my call center friend was too sad to hear my question.

I checked WhatsApp. It seemed like hours were passing by as the image was received, downloaded slowly, and I clicked open.

I saw it and I knew why his voice was so sad.

The owl was dead.

But it was not Hedwig.

I closed the image and deleted it. I called my call center friend back.

"It was not Hedwig, Shashtri. I will see you."

"Are you not leav-," he began, but I had disconnected the call.

I was leaving. Indeed, I was.

Ramesh was still apologetic after so many months.

"Sorry man, I should have watched her better," he said as he waved me into the airport.

"No worries, brother. Stay safe." I waved back to him.

Flight to Addis was uneventful.

I was heavy with emotion when we were about to land. From the air, Ethiopia was the same land. Beautiful, solemn and unconquered. Of the people, I was not sure.

We landed.

First thing I noticed was the weather. This is one thing I missed world over. Addis weather. It stayed a perfect 25C all year around. There was no extreme heat. No extreme cold. Stable and moderate. Always.

There were many Indians on my flight. Transit passengers. They will land in Addis, collect a RTPCR negative report overnight and be on the next flight to Canada.

Indians were resourceful. They always found a way.

There were two Eritrean families and one Kenyan. And a few Ethiopians, including me. Of them, only I was flying onwards.

I was the transit passenger.

My mother said I was fortunate. I felt less fortunate. I wanted to burst out of the airport, hire the first taxi and go the full 14 hour drive to Mekelle without stopping.

But instead, I went to Wudassie Diagnostic Center with the Indians and gave my sample for RTPCR testing to a most surprised technician. He possibly could not believe that I was a transit passenger too! I stayed at the hotel the Indians were staying in: New Day.

The room was good. But it had no air conditioning or fan, which the Indians with me were most surprised about. I told them it was not required here. Addis was moderate. At least, the climate remained moderate.

There was a phone in the room. A landline.

I wanted to call my mother from the local number and announce I would arrive the next day at home. How shocked would she be? How happy? She had not seen me in 3 years. But I used WhatsApp. I made a voice call. No video.

"I have reached, mother," I suppressed a sob. I just realised I called my mother, mother. It was not Amharic. It was unusual. I was different. Maybe I was not fortunate. But I was different.

My mother noticed the suppressed sob, but misinterpreted it.

"It does not matter," she said. "Go through Turkey this time. You will come to Mekelle soon enough. I will visit you in Canada sooner."

Her voice was firm. I did not disagree.

I had injera for dinner. I had missed it. Indians ate dosa, which is made of fermented lentils and rice. It is similar but injera is better. Teff is an ancient grain. It has the taste of history, and home.

I missed Hedwig. She liked bits of dosa and I always told her that she would like injera more.

I remembered and texted Ramesh that I had reached Addis. He was the only person who knew my flight path and asked to be kept in the loop.

I could not sleep that night. I stayed at the window. I watched the streets empty gradually as the city slowly fell asleep. Construction lights at the far off stadium were kept on. My mother said they were trying to finish it finally.

My window was open and I was breathing in as much of my native air as I could. It was as if I could take a lungful of it with me.

I slept resting on the windowsill.

I woke to a barn owl pecking on my window. It was still night. I slept back and when I woke next morning I was unsure if the owl was real or imagined. I felt like Hedwig a bit. I knew the land, but I did not belong. She had been abandoned by me. I had been abandoned by my fellow countrymen.

I had a package for my mother. She always complained that the screen was too small on her mobile to see me properly. I had bought her a tablet in India. I gave it at the hotel reception to courier to my mother. I paid them in dollars. I hoped dollars were goodwill enough for them to courier it.

I started for the airport with the Indians. I had not exchanged my US dollars for Ethiopian birr. People liked to be paid in dollars. The Indians had exchanged it to be safe. They tried to change birr back to dollar at the hotel. They could not. They tried it at the currency exchange in the airport. They could not. I paid for the cab in dollars and got the change in birr. I stored the birr safely in my bag. It was memory.

We collected the RTPCR test results on the way. Wudassie was near the airport. I half wished to test positive. It would have meant that I would be stuck in Ethiopia. Then I could have visited my mother. But she wanted me to go on. She also wanted to come later to Canada. Possibly soon. The war was worse now.

I had tested negative for the virus. I got the report.

Addis Ababa airport had had a massive recent upgrade. Foreign investment, I had read. I was too tired and emotional to notice it when I arrived. It was also at night. In the morning, the true extent of the expansion was apparent. It was huge previously. Now it was humongous.

I focused on the security personnel. Soldiers in full military attire. This is what my mother had warned about.

"Getting into Addis is easy. Getting out is my worry," her words rang in my head.

I walked in with the Indians. They were conversing in Kannada and I spoke a few broken sentences. They looked at me surprised. They thought I could understand all that they were saying from the time I had met them. I could not. I could only understand when they spoke slowly. Then also, only the simple sentences. But I wanted to fit in as they crossed the security. Language is a big part of fitting in. I should have spoken to them last night however. Now, they seemed a little suspicious of me. Maybe they thought I would have more secrets.

The security people asked me to remove my bag, my belt and my shoes. I was worried when they asked to remove my shoes. But they asked the Indians too. I emptied my pockets. I was not carrying anything except a pen. My bag had no metallic object. I had just my phone and no other electronics. I was the ideal transit passenger. Nondescript. Not rich. Certainly not fortunate.

I felt like Hedwig. She was non-descript. She was difficult to find. It was not good for her. Or me. I had tried hard to find her.

But for me, here, nondescript was good. I wanted to be the other Hedwig. One who escaped East Germany

I spoke with my Addis accent. Though my passport and my name gave me away for a Tigrayan, the security let me through.

I joined the Indians at the other end, and exclaimed in Kannada. I do not know what exactly I spoke. They were unsure too, but bought into my excitement. They were going to Canada finally. They were excited too.

Our excitement was short-lived. There was another security check inside the airport. Again, bags, belt, wallets and shoes. Full drill. We cleared it too, but were less excited afterwards. I was praying now.

I sat with the Indians. I dared not leave the group. I told them about my country. The coffee. In broken Kannada. Fitting in.

We got on the flight after another security check. This time the guard was stern.

"Why are you running away," he asked in Amharic. He was checking my shoes thoroughly. Too thoroughly, I thought. Almost as if he wanted to find fault with them.

"My mother is ill," I answered.

"So you are flying to your mother," he asked, still checking my shoes.

I nodded.

There was no problem with my shoes. Or my bag. Or my wallet. Or anything.

He shrugged and waved me on saying, "My mother is ill too. I am still here."

I nodded. Understandingly. But not showing sympathy. Sympathy is sometimes misinterpreted as pity. It is not taken well.

I walked on and rejoined my Indian group. They asked me in Kannada if I was OK. I nodded. I could not speak.

I got on the plane. A brand new Boeing 787 in Ethiopian livery. I still could not speak. I felt a range of emotions. I was not sure what all emotions this range comprised. I kept my face still. I was almost out. No reason to jinx it now.

I got into my seat and waited. I texted my mother and Ramesh that I had boarded my flight.

Mother asked me for a picture of Istanbul. Ramesh had not replied.

The flight attendant had explained the emergency protocols, when her senior cut in on the speaker.

"Ladies and gentlemen, please be seated. Our flight is ready for departure."

I had never heard a more welcome sentence.

I could feel my legs tingling when the Boeing turned and started to move.

"I am off. I am Hedwig"

***

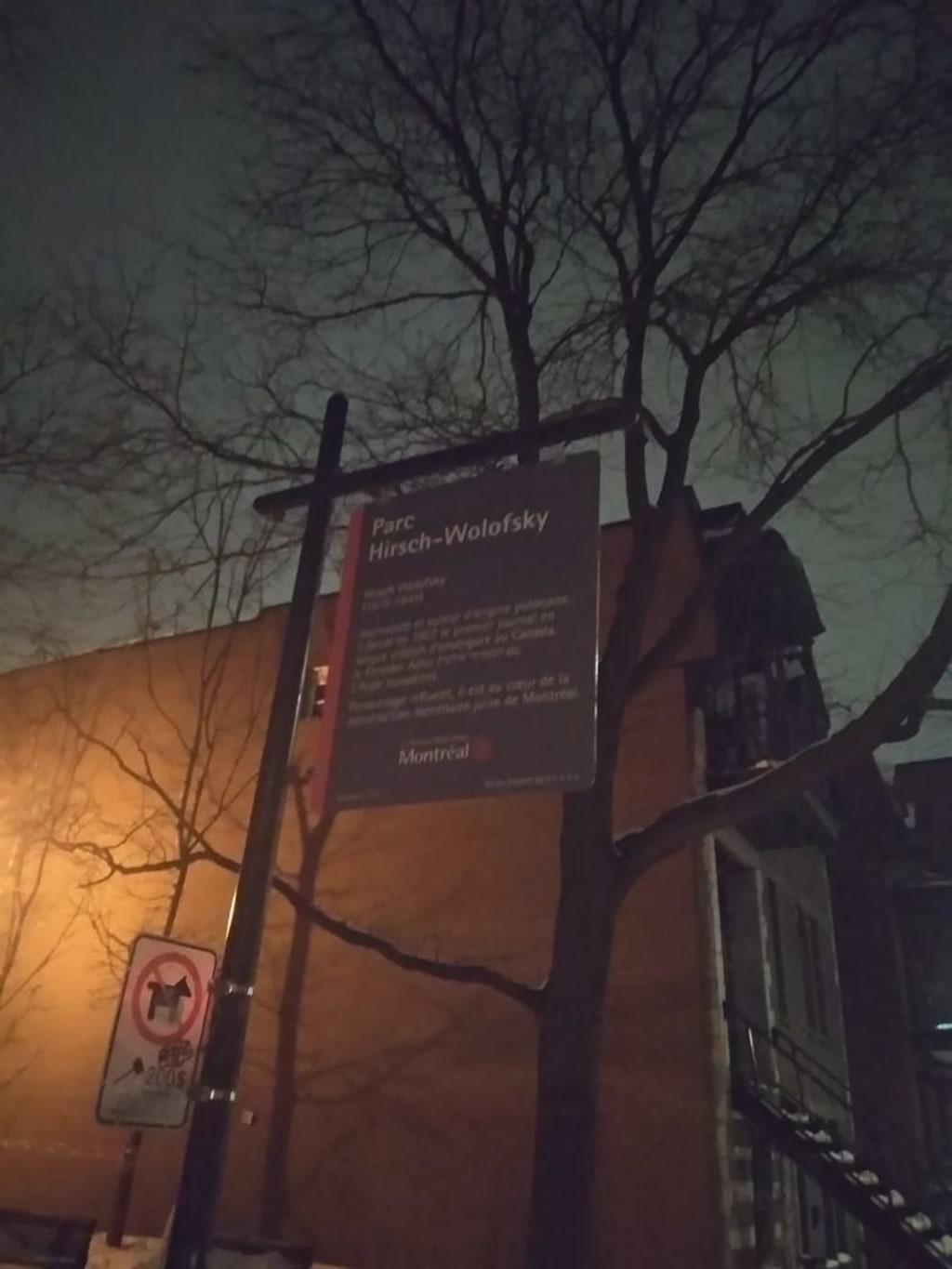

It was a small park near my house in Montreal. The park had two small swings for children, a slide and a bench for their mothers. There were pink hippo sculptures nearby that children climbed on.

I had seen them from my window as I quarantined and recovered from the virus. The weather had changed as I watched each day. The trees had shed their leaves. The first snows had fallen. I had never seen snow. It was white and beautiful. But I missed seeing the children play.

I walked down from my house and sat on the bench. I looked at the screen on my phone. The screen was big, but there was nothing to see on it. So, I looked at the swings. There were no children here today. It was too cold.

Maybe my kid would have liked it here. When he was small he liked the swings. He did not like cold so much. He said his owl never woke up during winters. He may not have liked the cold here.

But, he never reached here.

He was taken off the airline, I was told by his friend in India. He was taken somewhere. Where, I never found out. The airline denied it. But his friend sent me his tickets. He was in Addis. I searched for him. For months. And then, a full year. I pled to all who would listen.

Eventually, I accepted. I fled. It could not remain.

I sat on the bench in the cold. I saw an owl flying. It was white and big. And fleeing. Small ravens were on its tail mobbing it.

I remembered what Solomon had said, "Owls flee only when they are not near their home."

Maybe that is why my son was fleeing, and why I had fled. In search of a home.

I had started walking back to my house, when I noticed a plaque with the name and story of the park. Parc Hirsch-Wolofsky was named after another family that had fled. They had sought refuge, but found a home here. Maybe I will find one too.

About the Creator

Tusratta

Biophysicist and non-indigenous Montrealer in my early 30s. Ageing out of the system and finding my place with my pen.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.