There was nothing much else I could do at that point. I’d already done it all, and done it badly, firing the bridges behind me the minute I’d been clear of them. So when the call came, I went. My 28 days were up, and it was all I knew to do. That or the street, and even a farm 900 miles south sounded better than the street. At least it would be warm and dry, food to eat and a roof over me. And the street would always be there waiting when I burned this bridge, too, as I already assumed I would. If the old man was too much trouble to take care of, I’d just leave. It was six months. I could do anything for six months.

When the bus dropped me at the crossing, I still had miles to walk to the farm, so when I finally reached the gravel drive I was a mess of sweat and doubt and irritability. He was sitting on the front porch, rocking in that beaten up chair of his. Clearly waiting, that was for sure, but whether he was waiting for me or just waiting to die I didn’t know and didn’t care. He got to his feet when he saw me—not feeble but heading there—and stood holding his cane until I’d gotten up the two shallow steps.

“Hey, old man,” I said, not moving to hug him, nor he me. “Hey, boy,” he said. “Guess you ain’t too thrilled to be here. Can’t say I blame you. Come on in the house.”

“Get them bowls down out of that cabinet,” he said, and he spooned the stew into them and laid out a pan of cornbread and a bowl of butter on the little kitchen table. The stew smelled like country heaven, and I wanted it in my mouth, all of it, just turn the bowl up and guzzle. But my own contrariness stopped me before I even tasted it.

“I’m vegetarian,” I said, setting the bowl back on the table, hating the superior way I sounded the minute the words came out of me, even though part of me believed it was still true. Hadn’t stopped me eating that hamburger at the last bus stop, though.

My grandfather snorted as he blew on his stew to cool it. “You ain’t no vegetarian no more, boy,” he said, chuckling as he ate. “You’ll starve. Best get to it. We don’t waste good food.” There were carrots and new potatoes and chunks of meat glistening with fat, a thick brown gravy holding it all together, and I tried not to think of the goat pen I’d passed coming in. It was the best thing I’d ever tasted.

Before the week was out he’d begun to school me in the ways of the farm. How to tend the 100-year-old garden, turning the soil that had first been turned by his grandfather’s grandfather, mending the fence that kept out the deer and rabbits, learning that chickens were our friends for so many reasons: insect control and weed control and freely given fertilizer and eggs—always eggs, everywhere eggs. At the end of the day now there was a little dirt under my nails that wouldn’t scrub away. I’d had dirt under my nails before, often, but this was different. This was honest dirt and a man’s hands, not the shaking hands of a sick, self-absorbed boy who couldn’t be bothered to wash.

I’d learned the routine by then: hands scrubbed, supper done, then the firepit. I hated to admit to myself that I loved that time of day, but I did. The old man would sit and watch the sparks drift up from whatever limbs we’d thrown into the ring of stones, and without preamble the words would start to flood out of him, the gravel of his voice telling stories of the man’s youth and middle years and old age, all jumbled together in time and space and ordered in no logical way, just topic leading to topic, tears leading to laughter, laughter back to tears, long rambling stories punctuated at times by the incongruous high hoot of his mirth. It was like he was emptying himself of all his words, leaving them as legacy for the time when he couldn’t speak them any longer. We skipped from religion to politics to death, from sorrow over the loss of the grandmother I’d never known to joy over the size of the tomato crop. He delighted in the antics of the new baby goats and told me the names of the stars. He whistled or sang the calls of the many songbirds until he was sure I knew them. “Important to know who’s flying there above you,” he said. He spoke of lawnmower repair and the best way to churn goat butter, then straight from there into the feel of the first pair of long pants he’d ever owned and the flavor of the first kiss he’d ever stolen, of his love for the land and his fascination with the luna moths that flapped around our lanterns every night. He talked always of the importance of chickens—evidenced, he believed, by how many everyday phrases related to them. Pecking order. Home to roost. Flew the coop. Scarce as hen’s teeth. “It just goes to show they’re part of it all,” the old man said. “They’re the only dinosaurs who made it. Makes you see what’s possible, you set your mind to it.”

In the beginning, I only sat and listened, unwilling to thaw myself enough to be human. But without knowing how or when it happened, soon I realized I was matching him word for word, story for story. I had been so silent, so contained, for such a long, sad time, and now the old man had broken through the dam and the stories and the feelings just flooded. No one was more surprised than me.

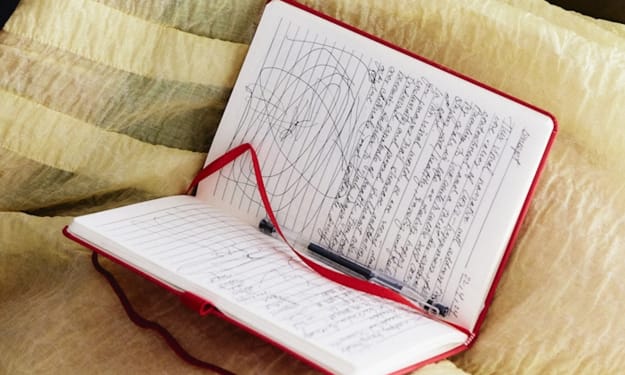

“I wish I had a computer,” I said one night. “There’s a book here. I think I could write it.”

“Of course you could,” the old man said. “My granddaddy was a storyteller. Storycatcher, they used to call them back when. I got a little of it in me, I reckon. Not enough to matter. But you beat all, boy. And you don’t need no computer. You take this. That’s all you need.”

The notebook he pulled out of his overalls was black and soft with age, battered and well-used, smooth with the wearing of his hands. I moved aside the elastic band which held it shut and saw that it was filled, page after page, with the old man’s writing. It was his life, in no apparent order. This page was a list of seed prices last year and the lineage of the goats he’d bred for decades. Next page was a poem written to his long dead wife. Sometimes there was just a phrase, a few words shy of a sentence. Pieces of stories he’d heard, old jokes that still made him laugh. It was his life, all in that small, worn book.

“You can just keep that,” he said, holding up his writing hand so I could see how deep the tremor had become. “Ain’t much use to me now. There’s good paper left in there.”

“It’d be faster with a computer,” I said. “It’ll take forever this way.”

“Hell, boy,” he said. “You got somewhere to be? You don’t need no computer. Just spitting out words fast as you can think them? That ain’t the way. You got to write it in your head first. Think it through. Slow and steady. Ain’t you never heard that tale about how the old turtle pulled one over on the rabbit? You’ve just had it backwards, is all. You done had it too fast for too long, and now you got to slow everything down. First you listen to what’s around you. Learn what’s inside you. Then you put it together in your head. Then you weed out the good parts and put them down to paper. You might get to a computer one day. But that time ain’t now. Now ain’t no time to rush. This here’s all you need.”

Using the little notebook went slow at first, just as the old man said. But as time went by and I began to see the things he wanted me to see, to become who he seemed to think I was, more and more the pages seemed to fill themselves. It was the beginning of the story I would write someday. His story. Our story.

At the end, the old man’s only worry was about after. “Farm should be your daddy’s,” he said, one of the last nights he could make it down those stairs to sit with me beside the firepit. “He don’t want it, but that’s how it’s gone since my granddaddy’s grandaddy and on back from there, so I don’t know how not to offer it to him. He’ll have it sold for a strip mall before I’m cold good. But I just don’t know no other way.” I hadn’t spoken to my father in almost seven years, but I knew the old man to be right. He wouldn’t see the beauty of it, he would only see the potential value.

“It ain’t worth much,” he said. “Not in dollars. But I’d sorely love to see you stay here. If we can figure out a way for your daddy to let you.”

I nodded, trying to find my voice and failing, knowing my father, knowing it would never happen. “Thank you,” I finally croaked out. “For everything. You’ve done more for me than anybody in my life. I love you. I hope you know that.”

“Hmph,” he said. “None of that, now. Come help me up. I got to get in the bed.”

Six weeks later, that bed was empty, but my heart was still full. Funny how those two things could exist together in the same space.

When the lawyer called to ask me to pick up the papers the old man had left for me, my duffel was already packed with only the things I’d come with. Plus the notebook. I’d never leave the notebook. And I’ll write that book, old man, I said to the air. Write it for both of us. See if I don’t.

I waited until I got back to the farm to open the lawyer’s letter. It was a single piece of paper with a key taped to it, and I recognized the old man’s shaky hand. “Left you something back there in that junk room, boy. I know you’ll do right by it. Love, Grandaddy.” It was the only time he’d ever used either word.

The junk room? I knew and hated that junk room. Every broken piece of furniture or tool the old man had ever owned and not been able to part with. But I put the key in the lock anyway.

It was empty except for a desk beside the window looking out on the big apple tree where the robins always nested. Beside the desk was a stack of black notebooks just like the one in my pocket, but pristine, clean, new. There was a laptop, new in the box, and in the envelope taped to it was the deed to the farm and land, not in my father’s name, but in mine. The rubber-banded stack of money was mostly crumpled tens and twenties with a few crisp hundreds on the bottom. Had it in his mattress, I thought, laughing and crying at the same time. Hadn’t been much for him to spend it on. $20,000 for a lifetime of his hard work. That amount of money would keep the farm going for years.

“It’s all yours, boy,” the note at the bottom said. “You write it all down, now.”

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.