The Change that Happens Late in Life

It's the natural order of things, but that doesn't lessen the pain

Her hand in mine.

The six of us continued looking at the machine with the numbers, watching, waiting. Top number was the heart rate; below that were other numbers: blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and respiration. The glowing digits in the darkened room changed every moment as the tendrils of tubes measured the last bits of my mother’s life. An hour earlier, I had jokingly bet which number would reach zero first – respiration. I would be right.

This began in June of 2018 when she fell and broke her hip and was rushed to St. Joseph’s in Tampa. Surgery was agreed upon, and then she was transferred to Solaris Rehab in Hudson afterward, the best in the county, I was told. Shortly thereafter she was rushed to a different hospital, Bayonet Point, after developing a blood clot and contracting pneumonia. Once released from there, she was checked into another rehab, Life Care. It was emotionally and physically draining for everyone, going from place to place, producing cards, signing papers, and remembering names.

My right hand held her right hand, her skin soft, worn, warm enough to indicate she was still with us. Across from me sat my nieces; Christa, who had flown in from Utah the day before; Stephanie, who moved from Ohio to visit her Gramma more often, and Ashley, a local niece who was entering the medical field. Dalia, the niece named after my mother was there; although she had a strict curfew, that didn’t keep her away from a woman so important in their lives. Their eyes were red, and fruitless were their attempts to keep up their spirits as the woman in front of us was dying. All we could do is listen to the constant hum of the machines.

Christa said, “I just found out our grandfather is dying, too. It’s a double pain.”

Stephanie added, “I just moved down to see Gramma more, and now this.”

Dalia looked at her sisters and said, “We knew it would be a matter of time.”

All of them had fond memories of my parents and the house they’d lived in for 44 years. Most holidays were celebrated at that house, everything from Christmas to Labor Day. My mom would look at the calendar and call me, "It's Arbor Day this weekend. Are you coming over?" As my parents got older, we started bringing the food over so they wouldn’t have to do anything but play with grandchildren in the pool or out in the giant 2-acre property. After my dad died, we brought Gramma to our houses to celebrate so there would be no fuss on her part. She’d insist on bringing something, including her world-famous candied yams. Holidays were to be shared, even if it was just hot dogs and beans on Memorial Day.

“I’m going to miss her,” Dalia softly spoke. That sentiment lived in everyone’s mind.

I had just flown in that morning from Washington. Her recovery at Life Care was slow but still going and her health was improving, so I felt that the trip I’d planned almost a year ago to visit a friend would be ok. Mom was ok with it; Del and my Aunt Cookie would be able to visit. I was at a northeastern tribal art exhibit in Vancouver with my friend John when I got the call.

“Hello?” I answered.

“Is this Barb Dukeman?” a man’s voice asked.

“Yes.”

“I understand your mother has a DNR on file. Since you have power of attorney, I need you to execute the DNR.” This was the beginning of the end. I didn’t even know she had taken back to another ER. To be legal, the doctor must have me on record saying it out loud: do not resuscitate my mother. It was her wish not to be kept alive like this; we’d spoken about it many times before. I had to repeat it, there in front of the fur pelts and Inuit pottery, this time so the doctor could record it over the phone. I felt so out of place; I was among different ancestors.

“Yes. She did not want to be resuscitated.”

After that call I just broke down sobbing. I’m sure the other patrons of the museum were uncomfortable and wondered what was going on. I just gave the OK for my mom to die. John hugged me, and we both cried. “It’s gonna be ok. It’s gonna be ok,” he kept telling me. My mom always liked him. Said he was “good people.”

I packed quickly and caught the next red-eye flight across the US and arrived around 7 in the morning. My son David drove me home so I could take a quick shower; we headed back to the hospital, the third one in less than two months. Not that it mattered to her. She had another contagious infection, C-Diff, along with low blood pressure, which brought her to the final hospital. Her body was too weak to fight the multiple infections.

“Are you OK?” David asked.

I didn’t know how to respond. In my mind, I said no, I’m not OK. My mother is about to die. The one who gave me life as I did for you. “I’m ok,” was what I said. You might have to do this for me one day.

The machines kept humming along, and a nurse’s aide came in to adjust the IVs and medicines as needed. The nurse practitioner asked me about her religion. I smiled and started in with the story of how the Catholic Church rejected her because she married a non-Catholic a few months before the Vatican changed the rules about mixed marriages. A Justice of the Peace joined my parents in matrimony, quite the scandal in an Italian family. As I was blathering on, Stephanie bluntly told me, “I think she means for last rites, Aunt Barbara.”

I lifted my head up. This thought had not crossed my mind. The DNR was surely just a precautionary measure. My mom would come back from this – she would still be sitting at her table Saturday mornings in no time, going through the mail, clipping coupons, and cutting articles and comics for my brother Del and me. I’d replace the water filter in her fridge, or change a light bulb that had gone out. She’d ask me to feed the cranes, the crows, and refill the hummingbird feeder. Taking care of her animals was very important to her, providing comfort and company. I politely declined religious intervention.

At Trinity Medical Center, she vacillated between vague lucidity and sleep. Legally blind, she would panic and call my name out over and over, even though I was right there holding her hand and trying to reassure her I was there. When I mentioned my sister-in-law’s name, Mary, she started repeating that over and over. In another panic, she called out for my dad once, calling him by his nickname, Yoyo. When she called for her mother, I knew things were getting worse. She didn’t get along well with her mother from some ancient bygone, but she was a dutiful daughter and took care of her each week just I did for my mother. My grandmother died 19 years earlier. Was she seeing them, or was her memory simply pulling up the past?

I tried to find something in the room to comfort her. She was in an isolation ward designed for contagious hospice patients, and we had to gown up and wear gloves every time we came in. No feeding tube, no ice chips, nothing I could do. Helpless to ease her physical discomfort, I took my phone and pulled up a playlist called Classical Mexican Mariachi.

I put my phone inside a disposable glove and set it on the bed beside her head. I pressed Play. Her lips moved as she tried to sing along. Familiar with the words, she wanted to sing along with some of her favorite singers, especially Jorge Negrete. Lost in the music, she calmed down.

“Si muero lejos de ti

que digan que estoy dormido

y que me traigan aquí

Que digan que estoy dormido

y que me traigan aquí”

This loosely translates to:

“If I die far from you

say they are asleep

and bring me here

Let them say that I am asleep

and bring me here.”

Her smile, mysterious in its reverie, gave an enigmatic feeling to the moment.

It was then I was asked about the IV meds and all the other care-should it continue? Because I had already enacted the DNR, I knew it was time even though I didn’t want to admit it. “I’d like her to have the pain medicine and oxygen. I don’t think...” I closed my eyes and shook my head. The attending nurse nodded and lowered the lights in the room, remaining by the door, a silent witness who had seen this happen many times before. My husband and oldest son stayed in background, allowing me to do what we knew would come next.

A few hours into the night I started a long story about our trips to the grocery store, recalling her routine in that store I helped her repeat every Saturday. It was one of the things she enjoyed doing – a huntress in the savannah of Publix. My voice, quiet as I narrated, matched the cold atmosphere of the room. I described her insistence that we go to the Dollar Store so she could buy her "bird food"; bread she cut up in little croutons to feed the cranes. Last stop was always the Natural Market. She enjoyed looking at the brightly-colored orchids outside the store. She complained about the prices of the vegetables, but she looked for whatever was in the clearance bin. A loaf of Cuban bread usually made it home with us; Cuban bread, sliced in half, smothered in Fleischmann’s margarine and eaten with black Maxwell house coffee. Our Saturdays, so familiar to her, were now being described for the last time. Tears cascaded down my nieces’ faces as my voice continued.

As the bright numbers on the vital signs monitor became lower, I told her, my words on the edge of a deep precipice, “Mom, it’s OK to go. You’ll be OK. It’ll be all right.” My nieces continued crying and stepped back from the bed, unable to witness the winnowing of her soul. I held my mother’s hand and watched the numbers zero out. My eyes became blurry. I was holding the hand of a dead woman, the woman who gave me life.

Looking down at my hand holding hers, my tears started, unbidden, and an unearthly sound came from my throat. This cry enveloped me and squeezed my chest; I couldn’t catch my breath.

My husband hugged me. “It’ll be ok. You were here. She’s at peace now.” I was lost; my guide, my best friend, mother, was gone.

~~~

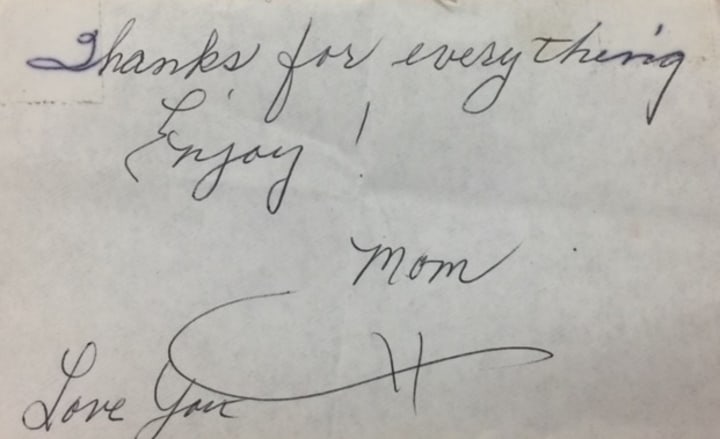

After a short memorial service and a spiteful sibling exiting the family on his own accord, I spent a few weeks going through her belongings. Years, actually. My other brother, gentle-hearted as my mother, was too fragile to handle the emotional stickiness that was to come. I knew this would be a long painful process for me; touching items she had touched, picking up the projects she left unfinished. She was perfectly clear on this: I was the only one to go into her bedroom, her sanctuary. I don’t know if I can do this, I thought. Just as she left it, the room was redolent of her scent; old perfume, musty photo albums, scraps of old material, ribbons, and tassels from the clothes and curtains she made. One entire wall had built-in bookshelves and cabinets, designed by my dad when they first built the house. Pack rats they were, and the shelves and cabinets were full of books, boxes, and assorted bagged up items. Everything was covered in a plastic bag. The single bed, next to the wall, had her old slippers and sneakers underneath. Her sheets, yellow and white daisies on a green background, were thin, worn, soft. Strands of white hair on her pillow.

Opening the cabinets, I started opening boxes and sorting through a lifetime of items. Another Corningware coffee pot. A box of Thanksgiving candles. More tissues and wrapping paper. The marble and wood stick used to measure a hem. Boxes of patterns. A bag of knitting thread on conical cardboard. Her old set of curlers and the plastic pins that held them in place. I was sad going through her things, treasures and relics stashed away into her past; these once gave her joy.

Inside the house, I took a break and sat down by the kitchen window to think about all that happened. The family split, the loss, and the work yet to come. Grief does terrible things to the mind, and foolish thoughts intrude where angels fear to tread. Sitting at the table I looked around at the items in the room that she looked at daily. Her corner hutch that supported a tiny water fountain with a ceramic girl holding cats. Colonial plates on the wall. Copper cups. A pile of bills and catalog orders waiting to be mailed out leaning against a glass candy dish. A plastic placemat with a vintage Coca-Cola picture. The clock on the wall.

The clock came from a favorite thrift store of theirs, Clara’s Closet, which closed long ago and become a food bank. There was a wicker pattern around the outside of the clock, and the numbers were big enough to see from her chair. The plastic that covered the face was reflective; it was almost 5:00, almost time to go home, to my family where the next generations needed tending.

As we drove away from the house, I considered it was now my turn to take her place. In time I’d be the Gramma, the built-in babysitter with a candy dish holding the hidden forbiddens, a pocket with dollar bills I'd stuff in their hands before leaving. I’d be the one my sons would turn to with perplexing questions as their families grew. They’d volunteer to change my serpentine belt or engine oil when it was needed. I’d forward them the discount coupons embedded in my email spam. I’d be the one texting them funny memes and cat videos, letting them know I’m thinking of them. I’d be going to their houses on the holidays. In the mornings I’d have my coffee outside with the crows and the cardinals for company. I would no longer be the youngest child, the only daughter, the baby girl. I would become the one who once quietly endured and suffered, strong and brittle at the same time, smiling until the next teardrops had to fall.

About the Creator

Barb Dukeman

I have three books published on Amazon if you want to read more. I have shorter pieces (less than 600 words at https://barbdukeman.substack.com/. Subscribe today if you like what you read here or just say Hi.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.