Revolution Runs In The Family.

My Great-grandfather, the Mexican Revolution, and the birth of my Feminism.

Have you ever wondered who your ancestors were? Where they lived? What they did, or what their lives were like? Have you ever wondered if some of their personalities, their ideals, beliefs, or convictions maybe -just maybe- trickled down the DNA ladder and unto you? Have you ever thought about how their decisions, choices, and actions may have affected who you are, what you believe in, how you act, or even where you are today?

Well, I’ll confess I hadn’t really given it much thought for quite a long time. That is until today when I remembered that a couple of months ago -out of nowhere- someone shared a YouTube video with my uncle, who then sent it to my brother, who shared it on our family group chat and sparked my interest and curiosity. So much so, that it led me down a rabbit hole of Mexican Revolution and Ancestry research, that ultimately helped me uncover more than I’d ever known about both my Great-grandfather and our family in general.

You see, when I was young my Grandfather Marco Antonio (on my Mom’s side) was never really open or outspoken about what his life had been growing up or what his family life was like. I remember he was always loving, and patient with us grandkids although he was also kind of serious, and quiet sometimes almost stern, or mean-looking. I guess like the men from before, the so-called “proper” (ahem, macho) men from his time, you know?

But to me, he was always -and still is- just good ol’ Grandpa. He used to take me and a couple of my younger cousins to work with him and would let us play freely around his office and the lot where he once sold used cars. Sometimes, he would even take a break from work and tell us stories while he drew us pictures of places he’d been to, or that were somehow special to him. I specifically remember one he drew me of a river he had once visited, I’m almost certain I have it stored somewhere.

But still, I did not know much about his past, his family, or let alone their story. I knew from the few times I’d dared to ask him about it when I was a kid, that it had not been an easy life. It had been quite a complicated one, considering that from a very young age he had dealt with the struggles of having a Revolutionary General for a father, with whom he very often butted heads. So much in fact, that it drove him to leave home at a very young age –around 15 or so- and move around the country working all kinds of jobs, just fending for himself.

And that was all I really knew, for the longest time. Until a few years ago when for the very first time, or at least that I could remember, he voluntarily shared with me, some stories from the time when he was younger. It was late afternoon and we were sitting in the TV room just passing the time by ourselves. The memory came to him from out of the blue -like they usually do now- and right in the middle of a conversation we were having, entirely about something else.

But with his wandering mind being like it is and with me, being used to it like I was, I simply tried to follow him as best I could and let him tell me all about “that one time when...”. The excitement eventually wore off, his mind inevitably wandered and he changed the subject, yet again. I can’t remember how or why exactly but at some point, he got up and came back with a watch in his hands, an old Citizen from his collection. It’s been one of my dearest possessions ever since.

The stories he shared with me that afternoon, were stories that I could tell, brought him a great deal of joy. Some I am sure, were even of fond memories and untold adventures, judging by the smile on his face while he told them out loud for the first time, in who knows how long. Others maybe brought him excitement or perhaps a little satisfaction. But sadly, I could also tell there were stories stained -if not filled- with struggles, and even pain at times. He mentioned the “General” (as he still refers to his father) on a few occasions.

So, after watching the video and having it unexplainably playing on a loop in the back of my head, I decided it was time. I had to try to find out as much as I could about who my ancestors were and what their life had been like; about this chapter in our history that was not simply relevant to our family’s story, but that of our state and perhaps even, our country. It was an inquiry into a part of my family’s history that was unknown to me still, but that had suddenly become overwhelmingly interesting.

I conducted a family survey and asked my relatives for stories, details, facts, or any information they could share about our ancestors; I dove into research, and hard. But sadly, I found that since the role they played was more prominently recognized in the local context rather than in the federal one, it wasn’t deemed relevant enough to be awarded inclusion in the mainstream Mexican History books. Which, simply means there is not a lot to be found -or at least not that I could find from abroad- but what can be found, left a rather lasting impression on me.

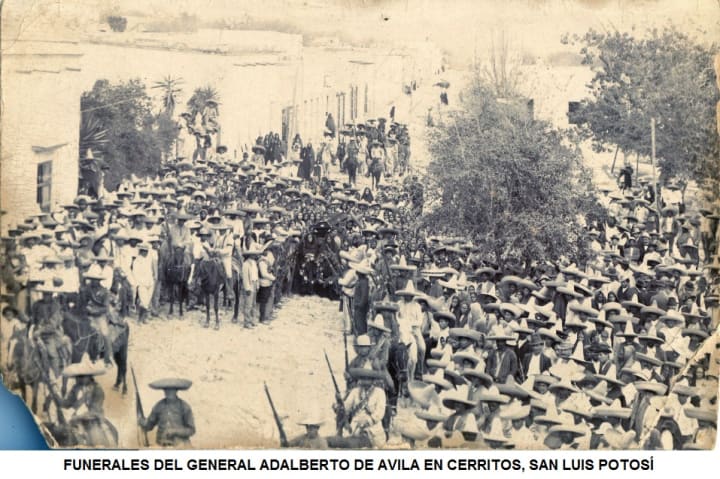

The video itself is quite simple, really. It is more of a presentation where antique photographs of Cerritos, San Luis Potosí (my Great-grandfather’s hometown), Cerritense people, and events from the time, transition through the screen. Meanwhile, a robotic voice narrates a summarized version of the historic events the “De Ávila brothers” were part of or involved in, along with some pretty notorious and widely known characters of the Mexican Revolution, the most important event of the XX century in Mexican history.

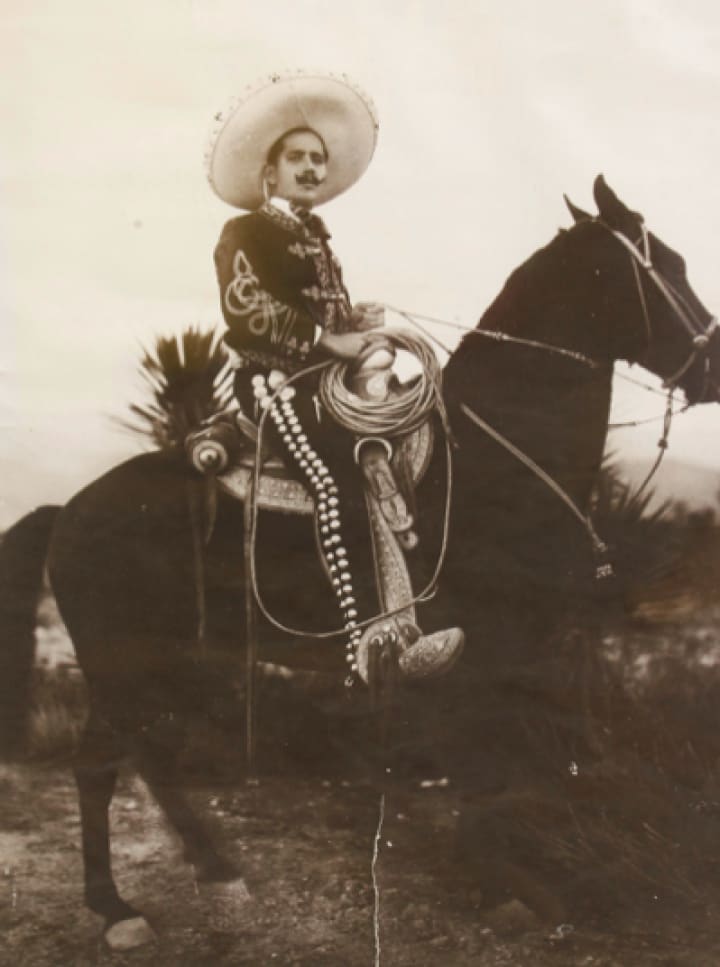

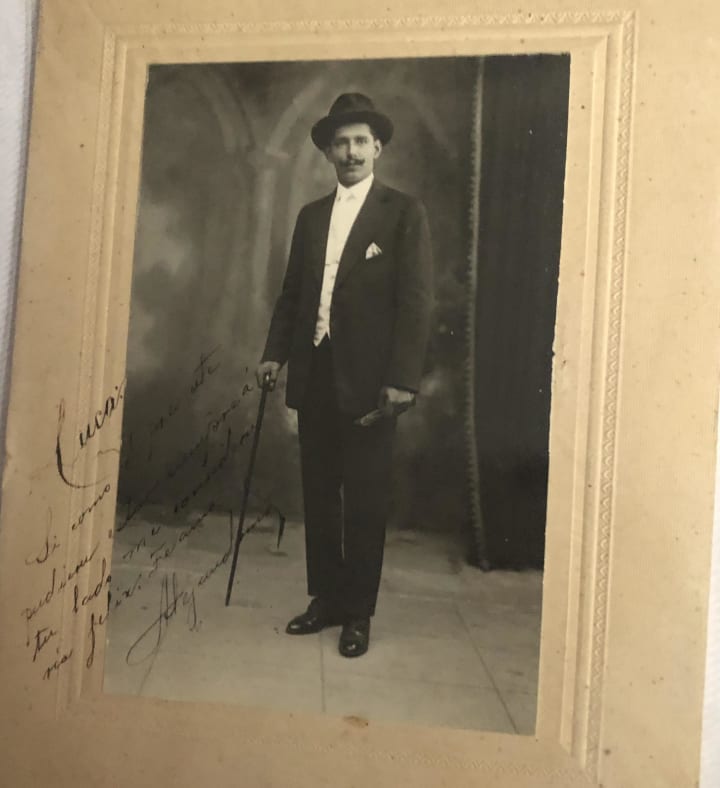

Born in Cerritos, a small municipality in the middle area of the state of San Luis Potosí in Mexico, on January 2nd 1892, Alejandrino De Ávila Rangel (1892-1958) was the second oldest son of the 7 children (unclear, there are varying reports) to Florencio De Ávila Torres (1856-1932) and María Rita Rangel De Ávila (1857-1916). His father was 36 when he was born and his mother María was 35.

Around 1900 according to municipal records, Don Florencio De Ávila Torres became the first constitutional Municipal President of Cerritos; and Rafael (one of Alejandrino’s reported nephews) was later reported as having been part of the patronage who built the central kiosk of the “Plaza de Armas” of Cerritos, which still stands to this day. Alejandrino, together with his father Florencio and his older brother Adalberto, has been named by some Mexican authors as an “outstanding family dynasty” in Cerritos’ society and Revolutionary Movement.

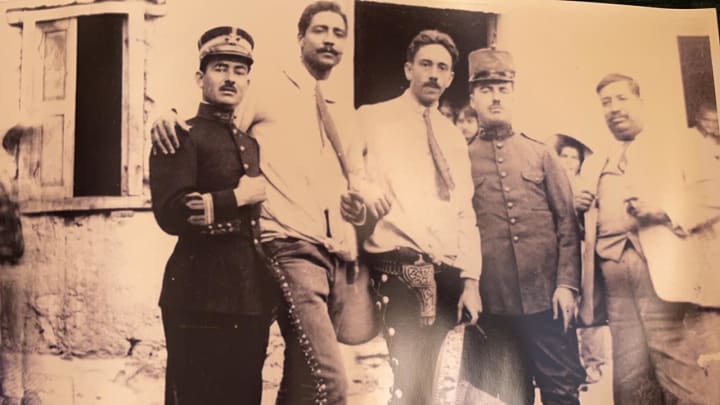

The particular chapter of my family’s history I chose to look into, involves both Alejandrino, who at a very young age became what some Mexican authors have called a “revolutionary leader” and an “illustrious man”; and his older brother, Adalberto De Ávila Rangel (1885-1915) whom, on the other hand, I’ve found has been referred to as both an “outstanding local and state revolutionary caudillo” and a “cruel bandit with a dual personality; a rebel with a vicious reputation”.

There were apparently multiple public reports of Adalberto’s abuses and crimes. Alejandrino, I also discovered, in an effort to protect his brother’s reputation once tried -unsuccessfully- to strongarm a retraction from the journalist who first made the claims and shamelessly called his brother an “ape”. Alejandrino, it seems, had what’s been deemed by some as a “less radical character” than his brother.

From what I gathered, their military history began when the older brother Adalberto, joined the Mexican Revolution around April of 1913. He militated with the Carrera Torres’ and the Cedillo’s groups and eventually reached the “General Brigadier” military status. He even wrote and published a manifesto in which he called his fellow citizens to arms. It was called the “Manifiesto al Pueblo Potosino” and over 5,000 copies were printed and distributed.

Alejandrino, the younger one, joined the Mexican Revolution right after his brother. He also militated with the Carrera Torres’ and the Cedillo’s, became a Coronel at first, and later reached “General Brigadier” military status. The De Ávila brothers first rose in arms against the Huertistas in 1913, while their father Florencio De Ávila was still the Municipal President of Cerritos.

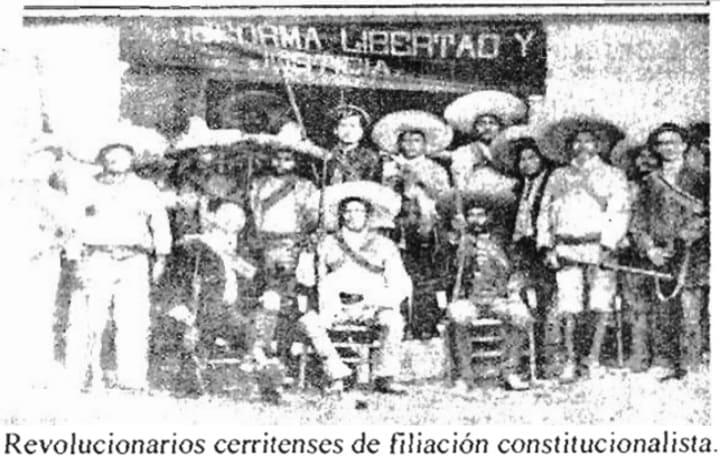

They rose against Antonio Medellín, a supposed “head voluntary” who took over Cerrito’s control while it was defenseless after the community had gone through multiple conflicts and changes in leadership, and who later became the head of the local Huertistas' forces. As Constitucionalistas themselves, the brothers were vehemently against Medellin’s recognition of the new Mexican federal government and how that prompted and even encouraged, the spread of Huertistas supporters in their hometown.

So, without enough financial -or otherwise- resources, without much support, or even enough weaponry, they rose; apparently relying solely upon their unwavering sense of purpose to try and overthrow the usurper. And surely, by 1914 Alejandrino had helped his brother Adalberto take the municipality of Cerritos from the Huertistas’ federal army in an armed and blood-soaked conflict.

The De Ávila brothers also founded a Revolutionary brigade named the “Aquiles Serdán”, made up of their loyal revolutionary followers; the largest military contingent of the municipality that ultimately, allowed them to have a tangible impact on local life during their time. Their ranks were full of diversity in regards to the social and economic origin of their members who were mostly peasants, countrymen, farmers, and people from rural backgrounds.

Men that along with the De Ávila brothers, found themselves fighting in a Revolution; waging a civil war against the oppressive federal regime of Porfirio Diaz’s dictatorship (that had already lasted over 30 years); and later opposing Francisco I. Madero’s substitute, and disappointing rule. One, that would later turn out to completely and radically transform de social and political structures of the whole country.

Obviously, those same men weren’t very pleased with, or rather, had a massive quarrel with, the comfortably-wealthy and influential upper-class that ruled their communities. So inevitably, the painfully obvious disparity that had led them into war in the first place also led the revolutionary forces of the De Ávila brothers to commit abuses and outrageous acts against the wealthy class of their municipality.

But their forces weren’t the only ones reportedly committing such atrocious acts. Adalberto himself, was once supposedly involved in the arson of a businessman’s property because he allegedly considered him to be a rival. It is said, he later went on to rebuild the place, and finally turned the rebuilt building into his very own office.

He was also later accused of having a close friend incarcerated, then demanding a huge ransom for his release, and eventually killing him when the family was unable to provide the full requested amount. He was often thought of as a bandit; infamous for the inflexibility of his decisions and for his constant and relentless undertaking of individuals he considered his adversaries in any way.

The brothers brought mayhem to Cerritos and its surrounding communities, that much is clear. Beginning around April of 1913 when Adalberto first emerged as an outstanding cabecilla, and along with his brother, participated in the conflicts of Agua del Toro and Las Trojes, where they received their “fire baptism” fighting against Medellin’s forces. Then with the foundation of the Constitucionalistas Cerritenses combative “Aquiles Serdán” brigade, that by the end of 1913 reportedly had hundreds of men in its ranks and whose operations covered a wide territory.

Brigade that, along with the forces of Magdaleno Cedillo and Cleto Galván, totaled around 600 hundred men that later took the town of Tula (in the neighboring state of Tamaulipas) after what was recorded as a long and violent siege. They were also reportedly involved in confrontations in La Herradura at the beginning of 1914. But more importantly, a brigade that, around May of that same year, supported the De Ávila brothers in their infamous taking “by blood and fire” of Cerritos itself in May of 1914.

The brothers’ violent revolutionary activities undoubtedly resulted in a tangible decrease in the quality of life of the Cerritense population. So much so, that around the same time the De Ávila brothers and their forces commanded the region, Cerritos found itself amid an acute economic and social crisis that was deeply aggravated by the constant recruitment of peasant men, taken from the fields and into the war. Which ultimately resulted in widespread hunger and eventually led to the depopulation and abandonment of several settlements.

After Cerritos fell and the brothers took control of the community and the railroad station, the revolutionary movement continued to extend its reach around the state and grew in both power and influence until their advancement on the state capital of San Luis Potosi was no longer impending, but underway. The “Aquiles Serdán” Brigade of Adalberto and Alejandrino, first positioned their forces in the hacienda of La Tinaja, a few kilometers outside of San Luis, along with those of General Carrera Torres, expecting a tough resistance and prolonged armed combats.

The taking of San Luis Potosi however, went significantly easier and better than the Constitucionalistas expected. The federal opposing forces had left the city without opposing resistance. So, with a clear path, the revolutionaries occupied the city by mid-July of 1914 and began the appointment of new state and municipal authorities, thus cementing their control over the state territory.

Once their dominance was clear, the entire Constitutionalist army, including the “Aquiles Serdán” Brigade of the De Ávila brothers, then marched towards Mexico City, taking villages that were still in the grasp of opposing forces. They arrived at the country’s capital by mid-August and participated in the “Valla de Honor” that was formed for Venustiano Carranza when he first headed to the “Palacio Nacional” to claim power over the country.

It’s said that during that same visit, Adalberto along with Donato Rodriguez and a “Capitán García”, had a private meeting where they had the opportunity to personally congratulate the new president on his rise to power. It’s also said that at that very same meeting, Adalberto asked the president for funding to be awarded for his brigade, which he reportedly obtained in the act.

Weeks after Venustiano Carranza’s ascension to power as the “Primer Jefe” of the Constitucionalistas Army of Mexico; elections were held to determine who would succeed him as head of the Federal Government, as per stipulations agreed upon from the Plan de Guadalupe. A Revolutionary Convention was then held in the city of Aguascalientes to name the successor and reach agreements between delegations.

Attendees of the Convention included Generals from all over the country who had actively participated in the armed conflicts. Agreements on many of the discussed topics were not reached. But they were all clear on one, they had to replace the President. Finally, after prolonged discussions, the vast majority agreed to no longer recognize the rule of Venustiano Carranza.

General Eulalio Gutierrez, then governor of the state of San Luis Potosi, was designated by the Aguascalientes Convention as the newly appointed “President of the Revolutionary Convention” and he assumed the coveted position of power. But many delegates were not in agreement with the decision, and some even questioned the convention’s legitimacy arguing it was General Francisco Villa who was behind the agreement itself, and that it solely benefitted him.

Later, when the prominent General Emiliano Zapata and even Francisco Villa himself withdrew their support, Eulalio’s rule only lasted from October 1914 until January 1915. Widespread confusion took over the different Revolutionary delegations and eventually an internal break and further conflict ensued. During this tumultuous time, shifts in both power and political views occurred; ideologies were redirected, convictions changed course, and rearrangement and division spread throughout the different Revolutionary delegations and their forces.

The De Ávila brothers eventually broke all relations with the Carrancistas, and publicly repudiated and stopped recognizing his rule, shifting allegiances to the Convencionistas. They later joined forces with the Northern Division of the Villistas movement. Finally, at the beginning of February 1915, the Villistas, led by General Tomás Urbina, took the capital city of San Luis Potosi and Adolfo Flores was eventually named Governor of the State. For the first time, a Cerritense was occupying the coveted state executive seat, even if it was only for a few days.

The Villista movement continued to spread and swiftly gained control over the eastern part of the state of San Luis Potosi; their reach extending to the borders of the Huasteca, where Carrancistas operated. By superior order of the General De Ávila, his forces were mobilized to fight along other Villistas against the Carrancistas mobilizing towards the port city of Tampico, Tamaulipas.

José Adalberto De Ávila Rangel died in combat on February 25 1915 in Ciudad Valles, when Alejandrino was merely 23 years old. However, his death is still considered polemic and remains rather unclear since there are two different and conflicting versions of how his life ended. One argues that he was killed by order of Adolfo Flores, the then Governor of the state, in the San Mateo Railroad Station in the municipality of Ciudad Valles.

The other, more gruesome version found in Gonzalo N. Santos’s memoirs, ascertains that Adalberto was killed while fighting the Carrancistas forces in the San Dieguito Station in Ciudad Valles. It also alleges that Adalberto and the Carrancistas’ Chief Arturo Careta, killed each other in a duel to the death, by emptying their guns on each other.

After Adalberto’s death, the Cerritense local life suffered significant improvements, since local forces left their posts and the Carrancistas coming from different parts of the state, took over and re-established their control after dealing with the lingering Cedillista movement. Three different parties took over the Municipal Government of Cerritos during this period: first, it was the Constitucionalistas, then the Villistas, and finally the Carrancistas.

And since the “Deavilistas” forces had lost their leader and founder, command fell unto his brother’s hands, the then-Coronel Alejandrino De Ávila, who from then on, decided to align with the interests of the Carrera Torres’ and the Cedillo’s. Alejandrino’s mother María Rita, passed away soon after his older brother, on June 13 1916 in Cerritos, San Luis Potosí, Mexico, at the age of 59.

By the decade of 1920 his father, Florencio de Ávila had continued to rise in power and had politically consolidated his position within the National Army, which allowed him to participate in the control of various aspects of the Cerritense population; even when his position had been questioned as a consequence of his accumulation of both political and economic capital during the Revolution.

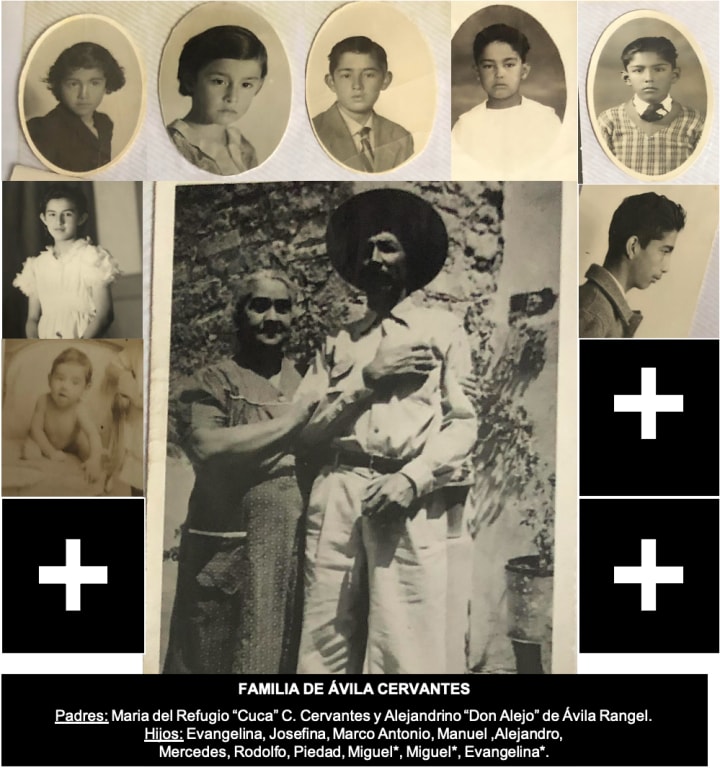

Around May of 1930, Alejandrino moved to the capital city of San Luis Potosí. His father Florencio, later passed away on December 3, 1932, in Cerritos, San Luis Potosí, Mexico, at the age of 76. On July 6, 1949, Alejandrino was married to Maria del Refugio Cerna Cervantes (1894-1988). The couple had 11 children of which unfortunately 3 died at very young ages; my Grandpa Marco Antonio is the sixth, with four sisters and three brothers. Alejandrino died on May 6th 1958 at the age of 66 in San Luis Potosí, México.

But why, or rather how, exactly does it all relate to the birth of my Feminism, you ask? Well to me, it is quite simple. You see, the Mexican Revolution was one of the first social revolutions of the XX century; a civil war that fought for equality, freedom, and justice; a movement born out of the awakening of the people to their unfairly precarious living conditions and the profoundly unjust social climate around the country. Essentially, it was the voice -and last resort- of the oppressed and exploited.

One of its core demands was for a genuine and democratic government that guaranteed wider social rights for all its citizens; a fair agricultural and educational reform and liberty and equality for all the people. But especially, for those who were constantly and blatantly overlooked by the rich and the powerful; those who were never considered for the arbitrary distribution of wealth, lands, and power, and who were either exploited for the profit of a few or abandoned to withstand the spread of injustice over all aspects of their lives.

It’s also fair to say, it was a blood-stained chapter in Mexican history. And although it absolutely brought insanely positive outcomes, like that of the promulgation of a New Constitution in 1917 that pioneered the recognition of social and labor rights, education, and healthcare, and unequivocally helped shape what our country is to this day; it was undoubtedly, also full with accounts of violence, bloodshed, abuses, and outrages earning it the title of one of Mexico’s most turmoiled times.

Nevertheless, it was also a movement full of fearless, strong, and pioneering women. Women who on occasion played the role of supporting forces to the armed men of the Revolution, and who also sometimes took part in the armed conflicts themselves. Women who participated in any way they could, who came from different backgrounds, and belonged to opposing parties; but who fought just as valiantly and just as hard as -if not harder than- any man.

Women who achieved great things amid a particularly challenging time during the last decades of the XIX and the first of the XX century, when for economic, cultural, and familiar reasons, they weren’t even allowed to study, participate in certain activities and professions (reserved for men), or let alone pursue a career. Women unafraid of passionately and repeatedly fighting their oppression by the overwhelmingly masculinized -if not blatantly machista- consciousness of our country.

These were the women who overcame a considerably hostile environment and relentlessly fought for their rights and those of their fellow citizens; but more importantly, women who, perhaps unconsciously, led the way and paved the path for the women’s rights movements of today. Women to whom we owe so much, yet whose stories and lives have systematically been overlooked and have somehow faded in our memories for over a century, essentially condemning them to oblivion.

Such was the case of Hermila Galindo Acosta de Topete (1886-1954) and Matilde Petra Montoya Lafragua (1859-1939), two of the countless illustrious women from the time. Matilde Montoya was the first woman doctor in Mexico’s history. An achievement she managed only by incessantly fighting for herself and her education; constantly facing rejection, harassment, judgment, and senseless accusations from her male counterparts who accused her of being immodest, impure, and dangerous.

She fought with all her might, even against institutions who relied on the most basic and minuscule “technicalities” to deny her access. She fought to the point where she even got the then President of Mexico, Porfirio Diaz himself, to intervene on her behalf twice. She finally graduated, and in 1923, she went on to found the “Asociación de Médicas Mexicanas”, the first female medical association in the country.

Hermila Galindo was president Venustiano Carranza’s particular secretary and a woman who undoubtedly played a fundamental part in Mexican history. She was an active promoter of women’s sexual education, in a time when it was considered immodest and was simply unheard-of. She fought for women’s right to vote and was also responsible for countless ideas and guidelines that were later included in the Constitution of 1917.

And all the female involvement did not go unnoticed by my ancestors, not only because of the positive aspect of their participation but rather because of the outrages that women were being forced to endure. It was considered a factor of such importance, it even had to be included in Adalberto’s 1913 call to arms, the “Manifiesto al Pueblo Potosino” (pg. 179) where he, among other things, wrote:

“… For three years our beloved soil has been stained with human blood; for three years the long-suffering Mexican people have struggled and fought with unprecedented efforts to save themselves from the tyrannical oppression of our evil rulers, who have wanted to make our free homeland a country of slaves. (…) The government wants to impose a shameful peace on us, which cannot be tolerated by a people who yearn for their freedom, who want respect for the law and the reign of justice. (…) The savage attacks committed on a daily basis... move even the coldest of hearts. Society has not realized it or is afraid to raise its voice, fearful of suffering the abuses of which so many citizens are victims (…). Brave Potosinos: Raise proud, wake up from your sleep and throw yourself against the tyrant, the one who enjoys imprisoning and murdering your brothers, the one who without regard and without precedent in history, imprisons the wives, mothers and sisters of your children, who safeguard freedom and demand the reign of justice. (…) A government of savages that assassinates innocents, that imprisons women without respect for their sex, murders children and the elderly, condemns men to the gallows, disregarding all respect for humanity and justice, commits the most horrible crimes, cannot be the government of a civilized country like ours. (…) Brave Potosinos fight, do not allow your rights to continue to be violated. Raise your powerful voice so that the Constitutional order is restored, and you will have fulfilled your duty as man and as a citizen.”

So today, a few days after the second annual “Marcha Feminista”, and the second annual “Paro Nacional” in Mexico, and during Women’s History month, I cannot deny these words have undoubtedly struck a nerve deep within me. It’s been 108 years since they were written -by a blood-relative of mine, no less- and I am deeply saddened, enraged, and I admit a little disheartened as well, that they remain absolutely true, to this day.

But what is also now certainly clear to me, is that the only way to achieve a lasting, and defining change, is to speak up, raise up and do what’s required to start and fuel the revolution we so desperately need. And I do not mean taking up arms, or using violence in any way to do so, I do not condone it in any way; but rather, be unafraid to employ the freedoms you currently hold to demand the rights you still lack.

So I wonder, if Alejandrino and Adalberto knew the Mexico we live in today, what would they say? If they knew, as we so painfully do, that in our country a woman or girl is raped every 2.3 minutes, and 11 women are murdered -with complete impunity- every single day, what would they do? How would they react? Would they encourage me, my family, my friends to raise up, as they did? Perhaps it is simply wishful thinking, and I may never get an answer, but I believe so.

Did I inherit any of my Great-grandfather’s Revolutionary ideals or traits? I also wonder sometimes. And yeah, perhaps it’s unscientific -or plain nonsense- on my part, but I simply can’t seem to stop wondering if perhaps whatever boiled in his blood and led him to join the Mexican Revolution, is what “allows” mine to boil today too. What I do know now, without a doubt in my heart, is that feminism is both my birthright and my obligation. And with luck, it will hopefully become our generation’s own Mexican Revolution.

About the Creator

monse cordero

MEXICAN | woman feminist | storyteller | music addict | pseudo runner

open-minded pragmatist living in canada, writing random personal stories and thoughts.

ig: @thememorablecactus

YXE | SLP

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insights

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.