He entered without knocking and left the door open behind him.

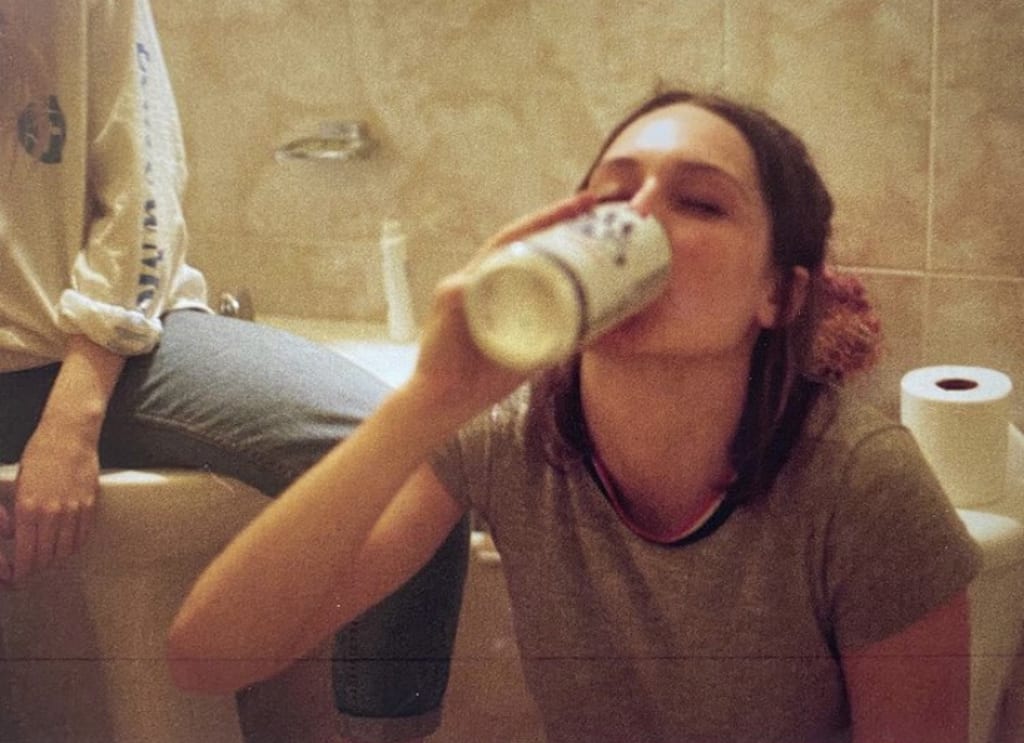

We’re out of bread, he said and placed a coffee on the edge of the bath for me.

I guess I must have liked this kind of intimacy once. Now it disgusted me.

I kept washing my hair, watching as he moved his mug up to his face. I knew he would become annoyed. He thought his annoyance annoyed me, but really it was his inability to wait for a drink to cool that annoyed me. The steam fogged his glasses and blurred his vision. He got annoyed and told me not to use all the hot water.

He was wearing the purple shirt I bought him in London from the Japanese chain store when you still had to travel to get good clothes, before you could buy everything online. Now the Japanese chain store was in every mall I went to and all of his shirts were from there, but this one was worn in the arms and faded around the collar. I asked him to pass me my toothbrush and the toothpaste.

I had told Hannah about the money the night before while we smoked and tried not to get wet from the rain. She had been to the hairdresser trying to emulate the hair colour of a woman in her film studies class. I told her it looked good and she told me I was changing the subject.

Maybe he’s got cancer or something. Have you asked him if he’s dying?

He’s not dying. This is just a thing that he does, I replied before clarifying that it had never been much, though. I just mean he has a way of inserting himself when you least expect it.

She said she wished her dad would insert himself with money before laughing and asking me to erase the memory of her using the words ‘insert’ and ‘dad’ in the same sentence. In high school, I spent an entire semester wondering if I was a lesbian because of how Hannah’s laugh made me feel. I wasn’t, but sometimes her laugh still made me wonder.

I’ll go, I told Will, spitting out the toothpaste between my feet. It had never been a question so much as a polite command because he knew I would say yes and go because I always said yes, and that’s just how we were together, our friends said. Our friends had been my friends, but then they became a shared commodity because that’s just what happens over time, they told me. It was unclear which of us would secure their loyalties in a breakup, but I guess that it would be a split with the majority to him. I was not a person who fought hard or convincingly for anything then.

I pulled an outfit from the cupboard - blue jeans, a white t-shirt and an oatmeal coloured jacket - and got dressed. My wardrobe was a selection of pieces I spent years quietly curating that allowed me to move through the world unremarkably without looking as if I was trying to be ironic. It was one of the few achievements I was truly proud of. Sometimes I wanted to show it to people who I believed would appreciate my efforts, but I knew that such an act would ultimately defeat the purpose of the wardrobe.

I walked down the hallway and said goodbye, grabbing a shopping bag to take with me.

You’re the best, he said from the sofa. He had moved to spread out with that morning’s newspaper, a copy which belonged to our neighbours.

The men who lived next door, a Vietnamese couple in their 40s who had tried out for The Amazing Race and worked in commercially creative jobs, were having their home renovated. An endless stream of tradespeople had gone in and out of the property every day for the past eight months. Hating them for this seemed futile to me, but taking their paper made Will feel good about the situation.

It was colder outside than I had expected. I thought about turning back to grab a beanie, but I liked the idea of possibly falling sick and having to spend a week in bed, so I kept walking down Bennett Street and looking into the front gardens that framed the terraces and thought about what to do.

Hannah said I should go on a holiday and live like a real adult where I could stay in hotels and eat at restaurants and take taxis instead of using airport shuttle trains like every other backpacker.

Go without Will, she said looking over her shoulder to make sure he wasn’t listening. Or, I dunno, invest the money and create a passive income stream and stop working by the time you’re 40.

The money arrived without warning or any real context, just an email saying he had released some funds and was giving $20,000 to each of us. I didn’t know what releasing funds meant but I would take his money because I always took his money.

There were five of us in total from one father and three women. I didn’t know the others, not really. I thought about which one I could call to ask them about the money, to see if it was normal to give away so much money, but I didn’t know if it was a lot of money or if it was weird for fathers to give money without warning or if they would even have my number saved.

I used to monitor the lives of my half-siblings through Facebook and would piece together who they were from photos and status updates that mostly talked about community issues or their political ideologies. They all voted Green, from what I could tell.

I analysed their comment sections and crafted the kind of inane observations that inserted me into the peripheral narrative of their lives without being threatening or meaningfully present. I’m here but not here, I would say through unoriginal and cliche birthday messages.

I told Will that it was hard to care about people when you don’t know them. We were on a date - when we still dated and went on dates - and talking about why he felt nobody seemed to care about the war in Syria. He told me it was biologically impossible for me to be truly disengaged from people who are genetically the same as you because it was behaviourally coded in us to pair with those we recognise.

The supermarket lights felt brighter that day, but maybe I was just dehydrated. When I saw Max I had already put a loaf of bread in my basket and was trying to decide what brand of cheddar to buy. I could just buy all of it, I thought. Not that I knew his name was Max then.

He was craning his neck out to look for someone he couldn’t see. It was probably because he was so short but the shelves packed with discounted special buys would not have helped.

I looked around not sure what I was looking for before I squatted and asked if he was okay. He said he had lost somebody, his mom and brother.

That’s okay, I told him. I lose people all the time too. If you tell me what they look like and I can help you find them, I said.

What do you mean, he asked. My mom looks like my mom.

Okay, I can work with that, I said. My name is Alice. I told him to hold onto the side of my shopping basket while we walked up and down the aisles looking for a woman with a face he would recognise as his genetic match.

It’s no big deal, I said. I didn’t know if that was true, but it seemed unlikely to me at that time that somebody would go through the hassle of falling pregnant and birthing a child only to dump them at the Italian grocers five years later. It seemed unlikely in that neighbourhood, anyway.

I didn’t know what would happen if I didn’t find her and thought about going home and announcing I had bought a child home with the food, like a surprise puppy or winning lottery ticket. The legal implications would be too great, I reasoned. Plus, somebody probably wanted him back.

Max told me about a boy in his class named Justin Eliasson who was allergic to everything, but especially peanuts. He could die if he ate one, Max said. I told him I had heard they could be pretty bad for some people.

I asked about his brother, and if he liked having a sibling. Not really, he said. He can’t hold up his own head and he always poos his pants. I took this to mean that his brother had been born with some kind of irreversible and devastating disability, but when we found his mom pushing a stroller I saw that his brother was a newborn, which was to say that he was boring from the perspective of Max at the time.

Max asked if I lived with any brothers or sisters or my parents. Just my boyfriend, I said. His name is Will. We don’t have any kids either. Just like friends and stuff. Max said it sounded cool and wanted to know if living with a boyfriend meant you could eat whenever you felt like it and watch what you wanted on TV. Basically, yeah, I said.

I had thought about breaking up with Will a lot that year. Not for any real reason other than I thought it might be good to feel lonely again. I knew that if I tried, though, he would make enough reasonable arguments that I would ultimately cave in and have wasted time I would not get back. I did not do especially good things with my time then, but I liked it all the same.

A woman screamed from the end of the laundry aisle before running towards us. This was Max’s mom, I realised. She was impossibly cool and thin and dressed like people noticing how cool and thin she was the ultimate compliment.

What have I told you about walking off? She grabbed his arm and pulled him into her.

Who are you, she asked, staring at me. I had not been prepared and was suddenly aware of all the ways I was probably not the kind of person parents would want their children to seek assistance from.

I said I was Alice and that Max had gotten lost and I had offered to help him because supermarkets can be really scary when you’re little and everything is so big.

She kept staring.

I’m really sorry, I said. I still don’t know why I apologised. Hannah said women apologised unnecessarily as a result of gender biases that are programmed into us before we can even talk.

Well, I’m Helen, she said, extending a suspiciously well-hydrated hand. It was as soft as Max’s, which seemed improbable given the age difference between them, but it really was.

Here, she said, pulling a black notebook and pen from the basket of the stroller where Max’s little brother slept. Give me your details, I’d like to say thank you properly when I’m not so flustered. I wrote down my number and name without asking why she didn’t have a phone like everybody else. Then it was the time where we said goodbye and began to walk away.

Thanks for hanging out with me, Max yelled from the other end of the aisle. I smiled back out of habit, but also because I really liked him.

My phone vibrated in my pocket. Hannah asked me to kill her before her hangover did. Will wanted toilet paper. I wondered if I should get a replacement newspaper, but the line at the newsagent was too long.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.