I died on a Tuesday.

It took me a while to understand what had happened. As I stood looking down at my lifeless body, I thought I was dreaming. Dazed, I watched as nurses came in and checked my pulse. I stared with numbness as the doctor proclaimed my time of death as 6:49 pm. As they unplugged the endless wires and tubes that had been attached to me, I stood by helplessly, slowly realizing this was it.

My life was over.

I had been diagnosed with stage four cancer almost six months prior, and the doctors had told me there was nothing they could do; it was far too advanced for treatment. I laughed when the doctor told me the cancer was in my lungs - I didn’t even smoke. If anything, it should have been my liver that went, because alcohol was my hydration method of choice. Much to my surprise, the battery of tests I was subjected to revealed that my liver was in pristine condition.

How ironic.

Less than a week after my diagnosis, I found myself in the hospital bed in which I would eventually die. I hated the hospital: the smell, the sounds, the sights - everything. My roommates tried to speak to me, but I had no interest in making new friends. What was the point? I was dying anyways. The only person I made an effort with was a young nurse, and the only reason I did that was because I needed her. Every Tuesday, she would come to my room and get $5 dollars from me while on her morning break, with which she would buy me a lottery ticket for that evening’s weekly draw.

I had played that lottery for over forty years, ever since I first immigrated to Canada . Every Tuesday, I would buy a ticket and wait anxiously for the results. I never won anything, but each week, I was convinced that would change. The lottery, called Lotto 649, was televised live on the last break of the six o’clock news, at exactly 6:49 pm every Tuesday.

6:49 pm on a Tuesday was what was recorded as my official time of death. I died on the exact day and time I looked forward to every week.

How ironic.

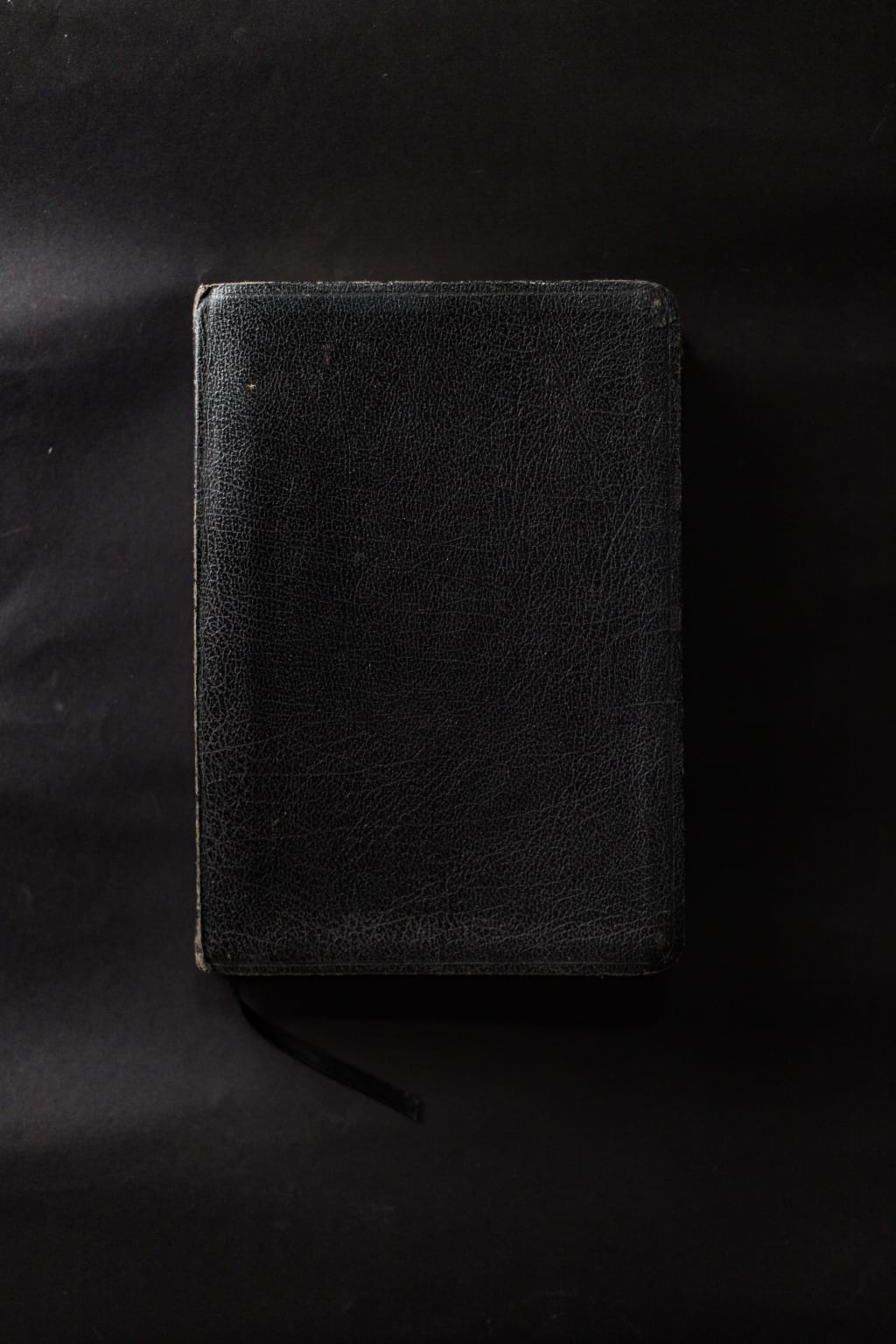

In addition to playing the lottery, the only sense of normalcy I was able to maintain while in the hospital was my habit of writing. Ever since I was a little boy, I had written obsessively in little black notebooks. It was one of the few things I enjoyed in life other than drinking. No matter what was happening, I would always make the time to sit down and write about my day.

Each year started off with a new notebook, but it couldn’t just be any notebook. I was very particular about what I wrote in. The cover had to be black and leather, the pages numbered, lined and dated. If it didn’t meet these requirements, it wasn’t worth writing in. Over the forty years I lived in Canada, I filled up forty of these notebooks with my thoughts and observations, one for each year.

As I stood watching my body being prepared to be removed from the room, my eyes shifted to my current notebook, which sat on the table next to my bed. My final entry was made earlier that day, my last thoughts on the world. That notebook was of no use to me now. My life was over; there was nothing left to write about anymore.

I died like I lived - alone and miserable. No one came to visit me while I was in the hospital unless I asked for something, and I don’t blame them.

I was a terrible human being.

I had a family, a son and wife, but the titles of father and husband were ones I never lived up to. I beat my wife regularly in fits of drunken rage, and my boy was more of a nuisance and inconvenience than a source of joy. I neglected my family and all of my responsibilities, instead focussing on having fun and living my life, which, in my opinion, was all about drinking, partying and doing everything I could to avoid being a family man.

As soon as my son was old enough not to have to rely on me, he stopped talking to me. My wife, emboldened by his decision, followed suit. We lived a life of illusion, putting on the front of a happy family, attending events together and laughing and smiling with our friends and relations. In reality, we were strangers living under the same roof.

I had heard stories of people who had experienced near death experiences where they saw a bright light and felt an inexplicable urge to go to it, but for me, no such light came. I simply walked out of the hospital and onto the street. I tried talking to people, but no one noticed I was there. I was invisible, a shadow amongst the living.

I walked all the way to my house, opened the front door and walked in, heading straight into my room. It had been tidied up since I last saw it, with all of my items placed nicely on the shelves that lined its walls. I sat on my bed and waited, wondering what would happen next.

A few hours later, my son entered the room with a box, which he placed on the desk in the corner of my room. I looked over his broad shoulders and saw my notebook and other items from the hospital in it.

As he was about to walk out of the door, my son stopped and turned back to the desk. I watched as he picked up my notebook and studied the cover, running his hands over the grainy leather, deep in thought. He and my wife had been forbidden from ever touching my notebooks, a rule I reinforced with a harsh beating when I caught him reading it once when he was a teenager. Now, even though he was an adult and I was dead, I could see the hesitation in his eyes as he held it in his hands.

Slowly, he opened the notebook and sat down on my bed and began to read, starting with the first entry. As he made his way through the pages, I stood across from him, wondering what he was thinking. When he got to the entry I had made earlier that day, my lottery ticket fell from the pages and into his lap. He picked it up and shook his head, wiping away tears. Placing my notebook on the desk and the ticket on top of it, he walked out of my room and sat down next to my wife. I sat across from them as they began to notify our friends and family about my passing.

Over the next few days, a steady stream of mourners filed through our home. I watched my son as he dutifully played his role of a loving son, accepting condolences and words of encouragement from the visitors. I stared with curiosity as my wife said kind things about me, knowing full well they were all lies. I knew both of them were doing this only out of a sense of duty, and for the first time ever, I admired them. Despite my death, they continued to put on an act to hide who I really was. I felt something stir inside me, and realized it was shame and regret.

I followed my son as he made funeral arrangements for me, realizing he had grown up to become a handsome and smart man. He had financed his own way through university, working nights to earn money for tuition, while attending classes during the day. He hadn’t even bothered asking me to help pay his fees, for he knew I would tell him I had no money.

My funeral was set for Saturday morning, at 10:00 am. The night before, I was sitting in my room when my son walked in. He sat on my bed for a few minutes, his brow furrowed in thought. Then, he picked up the lottery ticket and scanned it on his phone. A few seconds later, I heard the sound I had been waiting to hear for over 40 years.

The ticket was a winner.

I peered over his shoulder and saw what the final ticket I had ever purchased had won:

$20,000.

How ironic.

My son didn’t celebrate. He didn’t jump up for joy or scream. He just sat quietly. After what seemed like a lifetime, he went to the bookshelf and began pulling out my completed notebooks, one by one, reading each entry. He spent the entire night reading every detail of the last forty years of my life. When he was done, he walked out of the room with my most recent notebook and the winning ticket in hand.

I spent that night wondering what my son would do with his inheritance. It comforted me to know that despite the lousy life I had led, I had left him with something positive. Perhaps he could use the money to find a way to heal all the wounds I had left on him and his mother. Perhaps this was the universe giving me a way to redeem myself. Perhaps this would allow me to be remembered as something other than a deadbeat.

On the morning of my funeral, I was sitting in the kitchen when my son walked in and brewed himself a fresh cup of coffee. As he sat down at the table across from me, I watched as he pulled the lottery ticket out of his pocket, along with my notebook. He opened it up and began to write, but for some reason, the words were invisible to my eyes.

I watched my funeral with disinterest, standing next to my casket as mourners filed past. I listened as the priest recited the traditional prayers, and watched as my son stood over my casket and placed my small black notebook on my chest. A tear rolled down his cheek and fell onto the black leather cover. Slowly, he lowered the lid, and as darkness enveloped my body, I felt a similar blackness descend over my eyes.

I came to in a room in which the only source of light was a dim candle. Next to the candle was what appeared to be a book. I walked closer and picked it up, realizing I was holding my notebook. Confused, I opened it and turned to the last page, hoping I would be able to see what my son had written. As I looked down at his delicate yet confident writing, my hands shook with anxiety:

"Dad,

All I ever wanted from you was your love, but instead I got ridicule, scorn and abuse. After you died, I thought perhaps I would be able find something in your notebooks. I read every single one, from the first one down to your very last entry. I read about your life both before I was born and after. I read, read and read, but not once did I read anything that resembled love for me or mom.

All you cared about was yourself.

All that mattered was you.

You never once gave me the love a son deserves from his father. Not once.

You cared more for your lottery tickets than you did for me.

Love, dad. Love. That’s it. Nothing more.

Just a smile once in a while, a kind word of encouragement, a pat on the back. That’s all I ever wanted from you.

Goodbye dad, I hope wherever you are, you’ve found the happiness I could never provide you."

As I read the last words, my mind and body went numb. I turned the page and felt faint.

My winning ticket was tucked into the spine.

How ironic.

About the Creator

Gurp H.

Meditations on life.

Twitter: @forgeofman

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.