DO UNTO OTHERS, and sprinkle with a little Que Sera, Sera

A midwestern Boss Mama speaks quietly and carries big wisdom.

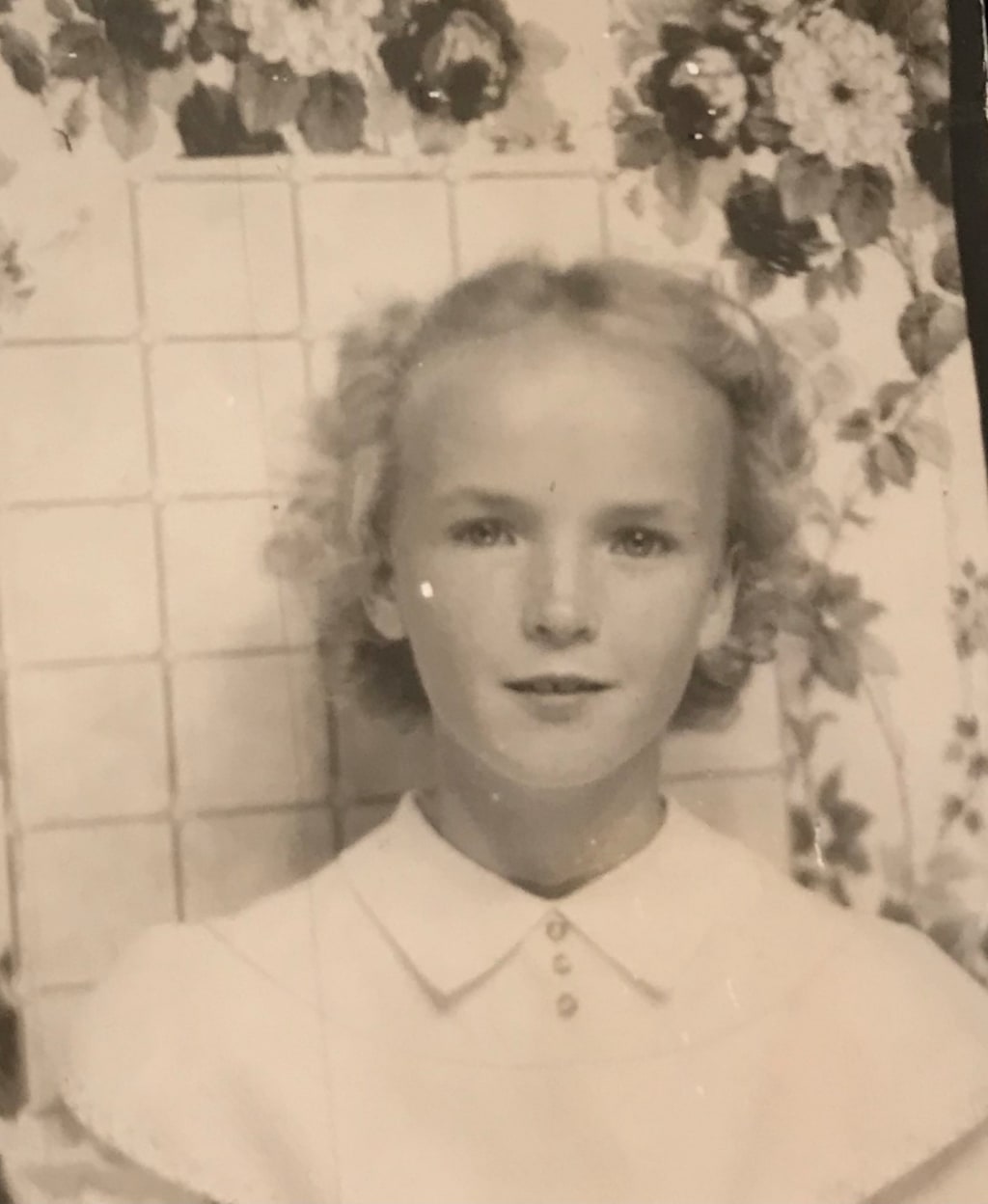

My mother, Donna, learned from the best, my grandmother, Laura, and then taught my sister and I to:

Do unto others…

Judge not, lest we be judged… And, finally, when all else failed,

Sing Que Sera, Sera, like you were Doris Day’s louder clone. Sing and know that no matter how hard you try, much in life will be up to fate, chance and/or the higher powers that be. Best to take a deep, shaky breath, and trust them all.

Donna’s mother, Laura, was a young mother herself, in a tiny farming community in North Missouri, when she found herself standing up to the status quo. It was the 1950’s and a gathering of high-minded, church-goin’, do-goodin’ ladies had gathered in their meeting place to discuss the new neighbors in town. Should they bring casseroles and desserts to Mercer County’s first African American couple? Or, perhaps make a statement by abandoning their ritual this once? The debate was heated. According to family lore, Laura had made up her mind well before the meeting, and not having a lot of time for “the silliness,” stood up and waved good-bye. She walked herself home, baked her famous pecan pie, quietly marched it over to the new resident’s house, introduced herself and gave them a warm welcome. Word is, the entirety of the ladies’ society, knowing Laura’s mind, tripped over each other to race home and do the same. The young couple were well-welcomed and became valued members of the community for generations.

Young Donna -- who’d seen first-hand “good” organizations judging and shunning folks based on race, religion or lack of, and creed -- grew to question authority or group edicts and make her own mindful and quiet decisions. After all, she chose to marry the poorest and probably most judged kid in town, who turned out to be honest, fun-loving and hardworking. For me, it was at first, odd growing up in Columbia, Missouri, a college town in the bible belt, without a religious membership. My sister and I were encouraged to make our own choices, and as social little girls on a boring Sunday morning, we chose to head to bible school at the neighboring Baptist Church. It looked fun: They played Red Rover, sang loudly (my own personal habit) and had snacks by the swings. My parents, both wounded at young ages by strict religions, encouraged us and diligently attended our deep-water baptisms, which were dramatically showcased in a room of water set behind a fishtank-like window above the raised pulpit. We were awed and impressed with ourselves, and we felt the fervent joy about us. The congregation, however, were concerned that two little girls were attending church without their parents, and we heard the talk. We worried a bit about hell ‘n’ damnation for our parents until we got to know the people better and saw that the day-to-day kindness of our mom and dad scored fairly high compared to the “saved.” We stopped worrying and enjoyed the freedom to wear what we liked to church; while our friends fidgeted in starched dresses and shiny shoes, we relaxed in blue jeans, embroidered peasant shirts and messy braids.

And then, as I became a good school student, I started hearing what we were all agreeing to in our Sunday school lessons. A lot of it didn’t feel right. We were all going to heaven happily, singing on golden highways, while other religions and folks, folks created by our God, folks who might have lived without hearing the good word, were doomed? My mother sighed when I told her my thoughts. She could have, so easily, said yes, Julie, this is right and this is good, believe in their god’s ways and stay with the group, but she didn’t. She said think hard, ask questions and follow your heart. I thought hard, I asked questions of my Sunday school teacher, who shut that sh-, “stuff” down FAST. Smart woman; she sent me to our Pastor Dr. Lively. We chatted lengthily. I was given a cold Pepsi and his full attention as we sat at his immense carved desk and the sunlight filtered in through jewel-toned stained glass. He carefully educated me about choosing Christ and its requirements and benefits. I got all that, I was onboard. But I had a concern, and only the strength of my mother’s encouragement helped me express it: What about, say, a kind woman who lives in the woods, helping and healing all people she meets, caring for animals (a huge plus in my young book), but for whatever reason, not accepting our god, perhaps due to not hearing about him OR choosing to hear, but kindly electing not to join the party? (It didn’t register then, but I had somewhat described my boss mom.)

Dr. Lively respectfully told me this kind woman would rest in Purgatory had she not heard, and “otherwise” had she not joined. He said it didn’t make him happy either, but that was an important part of what our church believed.

I think, like my grandmother, I had known my decision before the meeting. I thanked him for his time and told him I loved his church but could no longer attend if this was widely believed. He told me he admired my considerations and would always pray for me. We parted friends, and years later he would diligently visit my parents in the hospital and, without judgement, bestow warm blessings. We were always happy to see him, and Donna would remain lifelong friends with our neighbors who attended First Baptist.

I watched my mother carefully amongst other people and saw that, without an organized religion, she followed many ideas based on the Bible. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” and “Judge not lest ye be judged.” Years passed and she would wrestle with decisions but choose the kindest, and what I saw as the most Christian options. She was the person a neighbor would come to for advice; she gossiped little but cared more than any of them. I decided she would be alright.

Through the years, befriending people of numerous religions – Mormon, Muslim and Hindu classmates in my eclectic college town, Catholic college boyfriends and then, when I moved to New York, my Catholic husband, humanists, agnostics and atheists – I was surrounded by and investigated many schools of thought. I landed on my own form of prayer and belief in a higher, wiser power, and for this comforting belief, I thank god (and, yes, I see the irony). I thank my agnostic, free-thinking boss mom for encouraging me to find my own faith in my own time. In turn, my own son was encouraged to find his own way after learning about many religions, and I, and my mom, are thrilled he landed with his father’s quiet Catholicism.

Young Donna, upon returning to her farmhouse after speaking as her high school graduation valedictorian, found her suitcase packed and a train ticket to Kansas City, where her parents expected her to live and work. Too poor, she thought, to attend the University of Missouri, where she was offered a small scholarship, she boarded the train and began a long career of hard work. After marrying my father and having my sister and then me, she was a lunch lady and then worked for years on a factory’s night shift assembling electronic equipment. Throughout this hard schedule, when sleeping days and caring for children coincided, she dispensed wise advice, taught us to find the lesson in bad decisions and the humor in terrible ones. Bad things happened, they were discussed and a path back to happiness was found.

Incidents of growth that stand out, include the time my sister and I made fun of a strange young hitchhiker we were driving past. Donna pulled the car over and angrily berated us for judging this stranger from the comfort of our car, our well-fed life our unmolested pasts. Who were we to comment on a life we knew nothing of? Until we’d walked in her shoes, until we knew her pain, we were to hold judgement, to be kind. It was an uncommonly fierce speech and well remembered.

Years later, after moving to a new town for my father’s career as an electrical engineer, we survived his departure for another woman he met and loved. My mother’s heart was firmly broken, her life plans disrupted. A dark time ensued, when my sister and I grew up faster than wanted and when the song Donna had sang for us became a mantra for survival. Que Sera, Sera, whatever will be will be… were lyrics that would earn their keep for a lifetime, but especially after my father left. She’d sung the song with a smile to me as a child, when my little over-thinking and neurotic brain had questioned the endless fearful aspects of life. What if you get sick or die? What if there’s a nuclear war? How will I make money to live when I grow up? What if I’m no good at anything? Who will love me? Now -- when she faced a cross-state move back to our old hometown and the prospects of finding a better paid job with which to raise us, without the help and love of a husband – now, my sister and I sang it back to her in fearful voices. And she heard the words, and she trusted in herself and she worked hard as a deputy tax collector. She took good care of her daughters, making or buying special dresses for proms and creating economic vacations, and new traditions. She consoled us when we were hurt, cheered us when we needed it and followed our lives like they were the shows she’d bought the ticket for. And she most certainly learned to laugh again.

When I stupidly accepted a ride, at 16, from a drunken military school student and he grew aggressive, then angry and then wrecked the vehicle, she picked me up at the police station and somehow, hours later, while my tears were still falling, she made me laugh. When my dad forgot my birthdays. When my first love cheated. When I lost that scholarship. When I graduated from college and feared I would fail in my new journalism career in St. Louis. When I packed up my things for the new job, and drove, crying, away from her. Que, sera, sera. Whatever would be would be…and like my boss mom taught me, I learned I could handle it.

Two years after my first job, I was recruited for a P.R. firm in New York City. I could just afford the move and new rent, but it would be very tight, and my family had no money for me to fall back on. I knew no one there and I had a terrible tendency to get sick often, with fevers, strept throat, tachychardia. I drove back home to ask my mom, Donna, what she thought. I was pretty sure she would advise me to decline but urge me to enjoy the honor of having been asked. After all, she lived alone now, my sister was married and lived an hour away, she was wisely concerned about finances, and surely she would fear for my safety.

Yes, she said, yes to all those things. But tell me, do you want to live in New York and try this job out? Think hard.

I thought. Hard.

Yes, I said, I think I do but I’m so afraid.

Oh, well, she said, smiling, then you have to go. I know you, and I don’t think you’d want to let fear win.

I was thrilled, excited, nauseous, afraid -- her opinion had been all that had truly kept me back.

But, what, I asked, what if I do run out of money, get hurt, get sick, lose the job? Anything bad could happen, and I would be so far from you. You might need me …

She shrugged, pulled me into a hug, and sang in her soft, husky voice: Que sera, sera, whatever will be, will be, the future’s not ours to see, que sera, sera.

And, so very grateful, I moved to Manhattan, where I felt I had truly come home. I adored the city, and Donna visited me many times and learned to love my new town as well. I soon met my husband and we married. When our son turned four, ten years after I left Missouri, we moved to the suburbs, never straying more than a short train ride from New York City. Many, many times, as a new mother, in a new town, a new school, a new venture, I would ask my mother her advice and rely on all she taught me, praying her wisdom and the wisdom of my grandmother would filter through me, and then one day, onto my son.

Now, at 77, Donna has dementia which recently slid into the Alzheimer’s arena. With frontal lobe damage, she remembers most of her family and friends, but the past is slipping rapidly away. I use photographs and memories to retell her about our favorite vacations: the family cruises, the girl’s trip we took to Mexico with my sister and her daughter, the haunted hotel she and I visited at Gettysburg, the time we marched for women’s rights in D.C… It’s all news to her, and while she listens happily, as she holds one of her three cats in her lap, I often see her shoulders fall a bit at the immensity of all that she is losing. It was a hard transition, urging her two years ago to sell her home and move into an assisted living community. There she can stay in Missouri with her cats as long as possible, near to great-grandchildren and the towns she knows. Shortly after moving, she surrendered her car keys and my sister took over her finances and with each change, her eyes grew fearful. She would close them and take, deep, worrying breaths. What if I forget everything? How will I live? Who will I be?

Que, sera, sera, I still sing to her at these times, with a hug and a sometimes fearful smile. During the pandemic, through my bout with covid, through her loneliness and boredom, we’d share the song on our coffee talks on our Amazon Echo screens. And now, thanks be, in person again, we’ll sing it on long visits. When she hears the song, our mantra, she’ll look at me, doubtfully, much as I did as a child, and I’ll sing louder, as I like to, and then she’ll smile and join in. Together we can do as she learned from her boss mom, Laura, and as I learned from her:

Do unto others, judge not, and sing Que sera, sera.

Whatever will be, will be...

Thank you, Donna, my Boss Mom. You taught me and I have learned.

We got this.

About the Creator

Julie Anderson Slattery

Mizzou J-School alum, former NYC mag editor, writes horror and YA sci/fi, hikes with dogs, bikes, drinks beer, laughs, and plays with broken glass.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.