Death of an Artist

"Life imitates art far more than art imitates life." --Oscar Wilde

The day I bought my Dad a brand new car, he died. Not the way people say, “I’m dead,” at the end of a very unfunny joke, dead. Dead, he’s never coming back, dead. Cold hands, hard body, one-eye-open—dead. Dead like I watched them carry him down the stairs in a body bag dead. Dead like I went to the funeral and saw my little brother fall to his knees in front of the open casket dead. Dead like the crematorium sent me his remains in a shoe box dead. Dead. I’ll never hear his voice again dead. Dead, dead.

September 28

My twin and I celebrate our 22 birthday. We drink till we slur our words in the bar I work at, have worked at, will work at— till it dies or I die—whichever comes first.This night they play particularly bad music, with a particularly boring crowd. The boy I’m dating looks at me—me with my flaming red hair and red lips and my ripped jeans and black bustier top—and in a moment decides I’m too scandalous for his t-shirt and sweats flow—and besides, I don’t watch basketball— and makes a mental note to break up with me. I don’t know this yet, but I notice the space between us, and his many smoke breaks outside. I laugh and dance with my sister, as we’ve laughed and danced for years—through school, through waitressing, through 911 calls, through tears and tired eyes—the two of us today, 22. We go to the convenient store and buy over priced snacks (some of which are expired, but we don’t notice) then we walk to my apartment across the street and make frozen pizza and tacos and douse it all in salsa. And we sleep in a heap of our own crumbs. Rats peep their heads through my stove top, and rattle the dishes in my cupboard. The maintenance man sneaks in and steals 100$ bills from me. They're everywhere— in the carpet, under it, on my desk, inside it; the money that is—rats too. I don’t notice. I’m never home long enough to notice anything, even the decay of my own soul, drowned out as it is by the sea of customers that wave after drunken wave, never cease.

Thursday

I get an unusual, and unexpected call from my dad. He asks me how I’m doing, and I tell him I’m glad he called, and that it was actually perfect timing. He clears his throat as if the discomfort is lodged there. He says that 2 weeks ago, his car unexpectedly died. And he’s been unable to get to work ever since. He’s thought about his options. He couldn’t afford a new one, so he asked his boss for a loaner car. He asked Tony for a monetary loan. Both declined. He would’ve told me last time we talked, but we had such a good conversation he didn’t want to dampen the mood with bad news. I told him I’m glad he called me, and only wish it’d have been sooner. He said he found a car. I told him great. I’ll come home Sunday, and we’ll go to the dealership together. He starts about how he worked out how much he could pay me back. I tell him there’s no need. And I’m happy I could finally pay back in some small way everything he’s always done for us. My 15 minutes are up and I go back on the bar, flipping bottles, running taps, uncapping beers with a bar key gifted to me by a customer—custom painted with my name on one side, and a hummingbird in beautiful bright colors on the other. Of all the things I own, this is my favorite.

Friday

I bartend.

Saturday

I bartend.

Sunday

I bartend. At 3 am, my best friend picks me up from my apartment, and we head to NY together. My dad calls me at 6 am as we’re crossing the Tappan Zee bridge. He hasn’t slept. He’s worried. Are we almost there. We’re almost there Tata, see you soon.

We arrive. He opens the door and helps me carry in my heavy boxes. I take a nap.

He wakes me at noon. He made waffles and tea, all ready. He’s on the phone with his girlfriend. I look at his warm face and smiling eyes and think, there’s no one I’d rather be with. And it feels so good to be home.

Later that day

I head to the bank with my dad to get a cashers check for $20, 000. It is October 23, 2018. And for the first time in a long time, I feel alive, and all those dead dollar bills start to make a little sense. For a moment, my life feels worth something. I’m 22, nearly failing out of school, sleeping 2 hours a day and surviving off an all-liquid meal replacement diet because I can’t afford 10 minutes of time to sit down to a meal—but I can buy my Dad a car—the man who sacrificed everything for us— me, and my 3 siblings. Of all those times he came to the rescue when I needed help—stranded on a snow bank on the side of the highway, stranded in the woods with a sprained ankle, stranded—just stranded, he was always there for me. And finally, I could be there for him, too. And I think him knowing that was the blessing he needed.

Finally, we have the keys to the brand new Volvo XC60 in our hands. He lets me drive it back, and I follow him in my sister’s car—zipping through traffic together, on our way home.

That same evening

He has 6 hours left to live, but neither of us know it. We’re sitting on the couch eating take-out, celebrating. We’re sitting in the unheated, unfinished, uninhabited house on the pot-hole infested dirt road we call home. He takes a bite of an egg role, and puts his hand to his chest. I ask him if he’s ok. He says his heart’s pounding, like it’s nothing, and continues chewing anyway. So I think he’s fine. He’s my dad, after all, invincible. He stops and says, listen. I hear nothing—silence, a silence so still, so cold, and so deep it makes my skin crawl. It’s a silence I remember, that haunts me still. He says, “I come home from work, and this is what I hear—no one, nothing.” I ask him if he feels very different, now that he no longer takes his medicine (he lost health insurance after the divorce). He said, at first it felt fine—for the first 3 years, but this last year, he started noticing changes. He talks about how tired he is after work. And how sometimes he almost faints—how he has to sit down sometimes, or hold on to a rail. How he no longer goes on his daily 6 mile runs. I sit next to him and listen. What else can I do? Words can’t heal his heart. There are days I’d cry while I was away at school, just thinking about him, alone in this house—that ruined his marriage, that ruined his health, that is nothing but a ruin itself. In fact, I’ve been thinking about him a lot lately. For the past couple weeks every essay I wrote was about him—whether the assignment called for it or not, and I didn’t know why. It just happened. He gets up to go to sleep. And I think about reading him one of the essays I wrote. But the words never quite make it out of my mouth, and I figure there’s always tomorrow. So we say goodnight. And I ask him if he wants me to wake him up before I leave, to say goodbye, since I’m leaving so early. He says, of course. I stay on the couch, where I’ll sleep. He lingers at the foot of the stairs, as if he wants to say something. But he doesn’t. And he turns and walks up the stairs, for the last time he ever will.

I wake up at midnight with a hurting heart. Like a dagger in my chest, with someone twisting the blade. I walk to the bathroom and splash water on my face, using logic to dispel my fear. I’m 22, I’m healthy—it can’t be anything serious. Eventually, I fall back asleep.

My alarm goes off like an explosion. 4am. I call my best friend to make sure she’s awake, and ready for the drive back. Then I tidy the couch where I slept, and walk to the main entrance, where my dad and I had left the boxes I’d brought home from Boston. I carry them up the stairs so that my dad won’t have to later. I know my dad’s asleep, but I feel an inexplicable suspicion. Why am I being so tidy? I usually come and go like the wind. Why is it so quiet? I know he’s asleep, but I’m used to hearing his voice at odd hours of the night, talking to his girlfriend in a different time zone, or snoring, or calling my name if he hears me shuffling about. But the suspicion is suspended—a feeling originating from the gap of space between subconscious and conscious knowledge—and what I am about to see.

I pause outside his bedroom door. Afraid because I don’t know why I’m afraid. I shouldn’t be, but I am. I have no reason to be, logically. But emotions are rarely rational, and always accurate. You know what you feel when you feel it, even if you don’t know why. Sometimes our feelings know things before we do. At midnight, a piece of my heart died with his. I just wasn’t conscious of it yet.

With pounding heart, and pale hand, I gently knock on his door before opening it.

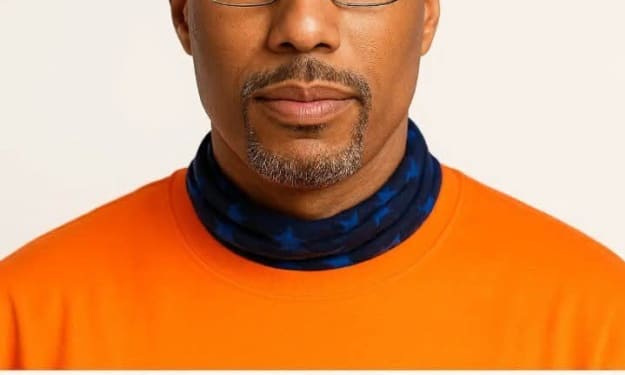

His nightlight is on, he’s lying on his back on top of his covers. He’s still in the clothes he wore to the dealership, sneakers, jeans, blue sweater I’d complimented him on earlier—brand new, he’d said, proud I’d noticed. Nothing unusual. It wasn’t until I walked closer, that I saw it. His left-eyelid half-open, looking up, unfocused. I stand there and stare as my brain simultaneously processes and rejects the reality of death. It must have been milliseconds, but they were milliseconds that stretched miles of infinite space, in a moment I would relive many times. I try waking him up. Choking, crying, calling his name as I have for so many years—but this time, there’s no answer. I lay my head on his chest, but there’s no warmth, no beating heart—and it’s cold and hard in a way that he never was. And when I put my hand in his, these hands that cut stone and painted monasteries and fed children—they felt like something that could break, like pottery, like glass, like wax—not a human, not a hand, not my hard-working dad.

So I’m alone in this unfinished house on a dirt road with my dead dad. And the shiny new car in the driveway. I sit next to him for the last moments I’ll have with him, listening to the silence he warned me about. Before it’s all lost to flashing lights, and wheels on gravel, and car doors closing, and phone calls, and messages I don’t want to read.

I return the car to pay for the funeral. I return to school, to work, to routine, slowly trying to process existing in a world in which my father no longer exists. And I begin writing, everyday, in my little black book. So that for at least a few minutes of everyday, he’s alive in memories I feel, in moments I’d write.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.