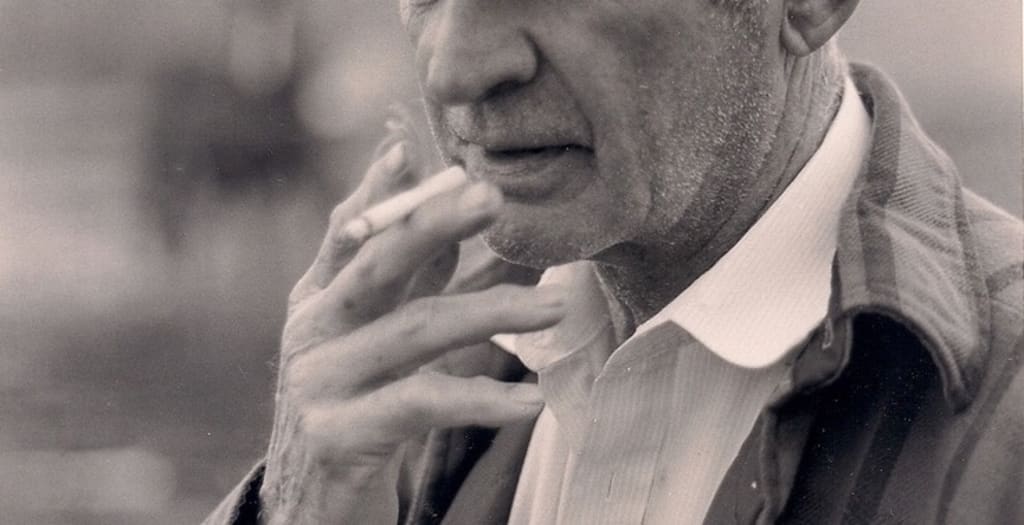

Papa Carlisle had been a man of systems. He said life should work like a train—one station leading to another, on a schedule. With order came reliability, and with reliability, happiness. That year I lived with him and grandma, he’d wake up every day at 6am and brew a pot of coffee. With a mug, two cigarettes, and the paper, he took the elevator down to the lobby and sat at a table under the awning out front. From his seat, the fifteen story high rise he managed ran straight toward the sky, like it was barely there. But I remember on those drives to Silver Spring, it towered over the strip malls and office buildings on Georgia Ave. He’d read the headlines, the sports page, then came back upstairs to set his book, leaning on the kitchen counter over a calculator, his reading glasses sliding down his nose.

By then, grandma had me up and dressed, got some breakfast in my stomach. If it was a school day, she’d pack my lunch and walk me to the bus stop. As the bus approached, she’d let go of my hand and kiss me on the head, saying, “You be good.” The way she narrowed her eyes at me before she smiled, I used to think it was judgment. I hadn’t learned to recognize worry.

If it was a weekend, I’d carry Papa Carlisle’s tool bag while he made his rounds. I was only ten—the brown leather kit was about as heavy as I could manage, but Carlisle said that was character building. He wore a different version of the same outfit—cotton button down, carpenter jeans belted high on his waist, officer’s shoes. These routines were traces of the navy along with the tattoos on his forearms. An anchor, a knot, a dagger through a heart with script that said True Love—Grandma insisted he kept them covered, said she was afraid people would see him as a lesser man.

This was the year my mom’s stewardess rotation put her on the northeast corridor, bouncing between RGA and JFK, then London twice a week. Dad was only halfway through his sentence, but she couldn’t turn down the promotion, the money. My grandparents were watching me half the week as it was. The transition was about as easy as it could be. Back then, I thought expressing unease came best through silence. I’d turned inward.

It was Saturday—we took the elevator up to the fifteenth floor, went the end of the hall and knocked on the door of the first unit. There were eight per floor, all one bedrooms and efficiencies where people had stashed their relatives who weren’t yet old enough for assisted living. Rather than sit around waiting for something to go wrong, Papa Carlisle did rounds. Five floors per day, a quick onceover on Saturdays, then rest on the Lord’s day. It took a moment for the tenants to hear the knock over their TVs. Most the time, these check-ins weren’t about upkeep or repairs as they were about making sure the tenant was getting along okay. He changed light bulbs, adjusted antenna’s on old sets, but typically, we just stood at the door and talked. When I started going with him, he said, “It’s nice to just let them know you’re there.”

#

The other thing about Papa Carlisle—he’d been a lifelong gambler. It was his only real affliction. He never fretted over his work, he’d taken care of his family, but he couldn’t stop himself from digging a hole. Before he’d been married and had my mom, he’d simply up and run from the debt. Later, he’d have to sell things, live thin, pick the family up and move to better work. As a child, my mom had gone from the Carolinas to Louisiana. Over the years, Papa Carlisle took contracts building houses straight up the Mississippi to St. Louis before they retired back east to be closer to my grandma’s family. They’d spent almost a decade in relative ease before he bet a little too deep on Clemson—his team. That’s why they sold the house in Richmond and moved up here to be a super, though they told everyone it was to be closer to my mother, to me. “Once you make a bad bet,” he said, “all the ones that follow are just as worthless. You start wagering desperation, not belief.”

The book was black leather with a strap, kept in his breast pocket next to a click pen. As the conversation came to a close, these old folks might say something like, “Oh, I got something for you,” with a nudge or a wink. They’d go and grab the sport page and whispered their wager as he jotted it down. If they forgot, Papa Carlisle would say something like, “In case you need anything,” and tap the book in his pocket. These were dollar bets—pick the winner, the over/under, individual stats. They’d ask him questions, and he’d read out the lines. It wasn’t about anyone making money, it was about giving people something to think about. These games are as much about principle and conviction as they are about chance. You take something that’s completely out of your control and you imagine you can see it the way no one else does. That confidence translates to the wager. Or maybe, these folks just needed the occasional win.

This was the Saturday before the Super Bowl—everyone had a bet. Most favored the Skins, the home team, though there were a few more sophisticated, more anxious thinkers who bet that the Bills were still hot from their run the year before. They didn’t fight their way back just to lose again. When he collected cash, he tallied it, then rolled it in a rubber band stashed in his jeans.

I didn’t like the idea of chance. I’d told my grandpa that. Why wager money on something that you can’t control? Chance, for him, was like a pulse, what gave all the order in his life some movement—a break from the routine. You believe in the will of the world and there’s an opportunity you’ll be rewarded for it. “Your dad flew on a plane one time in his life, and along the way he met your mom,” Papa Carlisle said. “You don’t find anything wonderful about that?”

#

There were repairs, too. The plumbing in the building was going. Most the time we fixed clogged sinks, drippy faucets. Papa Carlisle would have his upper body up under the cabinets, and I’d be squatting next to him, handing him tools. This was when he’d roll up his sleeves, when I got to see his tattoos. They’d once been black, but time had worn them blue, the lines broken by the wrinkles in his skin. I asked him if he still liked them even though they’d gone ugly.

“I was engaged to grandma when I shipped to Korea,” he said, his voice lost in the dark under the sink. “I didn’t hear from her for three months. I figured she just moved on.” When he was on leave in Japan, someone in his platoon bought a gun and some ink. Carlisle got one, then lined up the next day, and the next. He spent a week getting tattooed in mourning, or in spite of it. Turns out, Carlisle looked strange in my grandma’s cursive, and the letters she’d sent got delivered to the wrong sailor. “You’ll get it one day,” he said. “I don’t care how they look. It’s just nice to be reminded.”

My dad had his back covered in scripture and celestials dragons, the red and gold scales warming in the tan of his skin. A lot of that year, I’d blamed it all going wrong on my father. He was the one that wrote bad checks, that wouldn’t pay child support. Then he was gone for four years. I didn’t hate him, I hated his absence. I never learned not to. When I spoke ill of him, though, Papa Carlisle would hush me. “Your father is just a man, same as the rest of us,” he said.

In the evening, we gathered trash from each floor on a cart and took it out back to the dumpster. After, we strolled the lawn that separated the building from the road, picking up cigarette butts and litter. He said, “Who you got for tomorrow?” But I didn’t have a bet, hadn’t been thinking of the game. I shrugged, and he took the book from his pocket, clicked the pen. He said, “Twenty dollars, on me.”

We stood on the curb awhile, watching cars pass on the cross street. Our shadows drew a line across the pavement. I’d never held a twenty much less knew how to lose it. He set the ballpoint to the page a moment, then his arm dropped. When he sat down, I did the same. He said, “It doesn’t matter who you pick, it’ll work out either way.” To him, losing just meant adjusting perception. It meant reevaluating what you understood, a reanalysis of the unpredictable interactions and events you were stuck on the sidelines watching. He said, “All you have to do is trust yourself. If you’re wrong, it’s cause you didn’t know enough yet to be right.”

He wrote something in the book, then reset the band around it. Three times, he tapped the binding with the pen as if it were a wand and he was a magician performing a trick. Sliding the book into his pocket, he said he’d show me. He placed the bet, but it was a bet for me, for his belief in me. “I’ll take the winnings and make another wager, and another, and when you need it, it’s yours,” he said. He touched his finger to his chin. “But don’t you tell your grandma.”

He’d turned, waiting for me to look at him.

I said, “What if it’s wrong?”

“Then I’ll just start another roll,” he said. “It’ll work out. Just have to know how to believe.”

#

It didn’t work out. Or really, who knows what that even means. My mom took a job in customer service and tried to put it back together with my dad. It went okay until it didn’t. That happens all the time.

Papa Carlisle passed just after Thanksgiving this year, before I came home for winter break. I’d like to say that even after I’d moved back in with my mom, my family visited them often. We lived just a bit up the road. But there was always something keeping us busy except on holidays and the usual stuff.

He didn’t have much but left a list of who he’d like to see get what. I was to receive his toolkit. I’d driven six hours back to school before I opened it, before I found the cash tucked away in the bottom, neatly rolled in rubber bands. He didn’t leave a note—no instructions or wishes—just twenty thousand stuffed under a set of socket wrenches still wet with grease. I’ve never placed a bet, but I can hear his voice in the money. I keep waiting to feel like I’ve earned it.

#

Grandma won’t move out of the apartment, even though my mom has offered her a room and comes by half the week to check on her. They bicker, but it ends when Grandma says, “This was our home.” I’ve got a few years left in school. I don’t get to see her as much as I’d like to. When I visit, we usually just sit and watch TV. I write her every couple weeks, though, telling her about this and that. She can barely decipher my awful handwriting. My mom has to translate it. But how lovely, Grandma says, checking the mail and seeing her name written, by hand, on the envelope.

About the Creator

David E. Yee

Columbus, Ohio

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.