Understanding Chemical Equilibrium and Constants

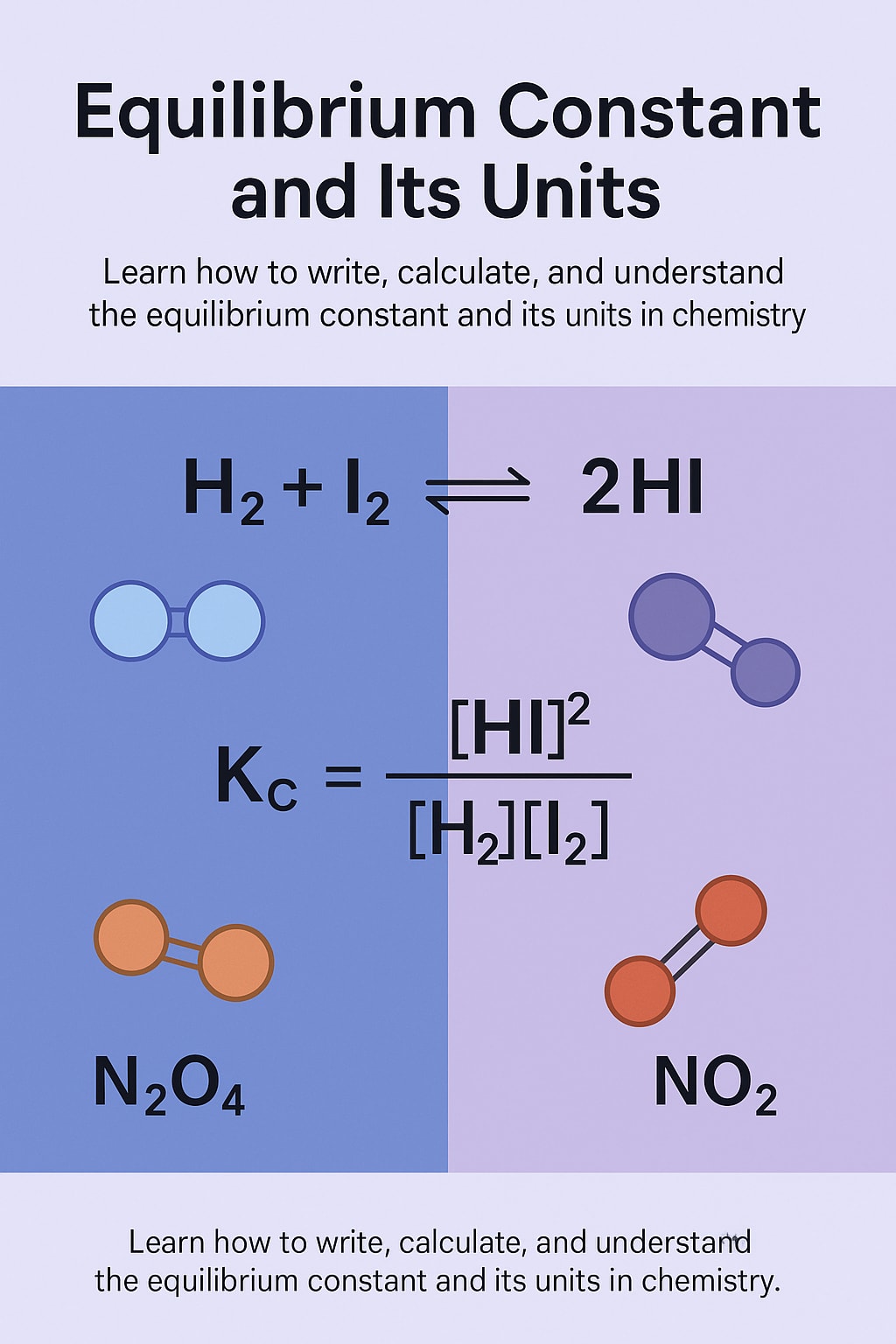

Learn how to write, calculate, and understand the equilibrium constant and its units in chemistry.

In chemical reactions, especially reversible ones, a state of balance is often reached where the concentrations of reactants and products no longer change with time. This state is called chemical equilibrium. To describe this balance mathematically, scientists use a term called the equilibrium constant, denoted as K or more specifically as Kc when dealing with concentration.

What Is the Equilibrium Constant?

The equilibrium constant (Kc) is a numerical value that expresses the ratio of the concentrations of the products to the concentrations of the reactants in a reversible chemical reaction at equilibrium. It helps chemists understand the position of equilibrium — whether it lies more toward the products or the reactants.

For a general reversible reaction:

aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD

The equilibrium constant expression (Kc) is written as:

Kc = ([C]^c × [D]^d) / ([A]^a × [B]^b)

Here,

[A], [B], [C], and [D] represent the concentrations of the substances A, B, C, and D, respectively.

The lowercase letters a, b, c, and d are the stoichiometric coefficients from the balanced chemical equation.

Concentrations are usually expressed in mol/dm³ (moles per cubic decimeter).

This formula tells us that products go in the numerator and reactants go in the denominator. Each concentration is raised to the power of its corresponding coefficient from the balanced equation.

Why Is Kc Important?

The value of Kc gives insight into the extent of a chemical reaction:

If Kc is large (Kc >> 1), the equilibrium lies towards the products. This means that, at equilibrium, the concentrations of products are much higher than those of the reactants.

If Kc is small (Kc << 1), the equilibrium lies toward the reactants.

If Kc is close to 1, both products and reactants are present in significant amounts at equilibrium.

Writing the Equilibrium Expression

Let’s consider a simple example:

H₂(g) + I₂(g) ⇌ 2HI(g)

The equilibrium constant expression would be:

Kc = [HI]² / ([H₂] × [I₂])

Note:

Products: HI is in the numerator, raised to the power of 2 (its coefficient).

Reactants: H₂ and I₂ are in the denominator.

What Do the Square Brackets Mean?

In chemistry, square brackets like [HI] represent the concentration of a substance in moles per cubic decimeter (mol/dm³). So, [HI] means "the concentration of HI".

Units of the Equilibrium Constant

The units of Kc depend on the net change in the number of moles of gas during the reaction. There’s no fixed unit for Kc because it changes depending on the reaction.

Let’s break this down with an example:

Example 1:

N₂O₄(g) ⇌ 2NO₂(g)

Kc = [NO₂]² / [N₂O₄]

Units:

[NO₂]² = (mol/dm³)² = mol²/dm⁶

[N₂O₄] = mol/dm³

So,

Units of Kc = mol²/dm⁶ ÷ mol/dm³ = mol/dm³

Example 2:

H₂(g) + I₂(g) ⇌ 2HI(g)

Kc = [HI]² / ([H₂] × [I₂])

Here, number of moles of gas on both sides = 2

So, units cancel out:

[HI]² = mol²/dm⁶

[H₂] × [I₂] = mol²/dm⁶

Kc = mol²/dm⁶ ÷ mol²/dm⁶ = unitless

Example 3:

2SO₂(g) + O₂(g) ⇌ 2SO₃(g)

Kc = [SO₃]² / ([SO₂]² × [O₂])

[SO₃]² = mol²/dm⁶

[SO₂]² × [O₂] = mol²/dm⁶ × mol/dm³ = mol³/dm⁹

Kc = mol²/dm⁶ ÷ mol³/dm⁹ = 1/(mol/dm³) = dm³/mol

So, for each reaction, the unit of Kc depends on the difference in moles of gaseous products and reactants.

Important Notes:

Only substances in gaseous (g) and aqueous (aq) states appear in the equilibrium expression.

Solids (s) and pure liquids (l) are not included because their concentrations remain constant.

How Is Kc Determined?

The value of Kc is determined experimentally by measuring the concentrations of all reactants and products at equilibrium. Once the concentrations are known, they are substituted into the Kc expression to calculate the value.

Conclusion:

The equilibrium constant is a powerful tool in chemistry that helps us understand and predict the behavior of chemical systems at equilibrium. By knowing how to write and interpret the equilibrium constant expression, and how to determine its units, students and scientists can analyze a wide range of chemical reactions more effectively

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.