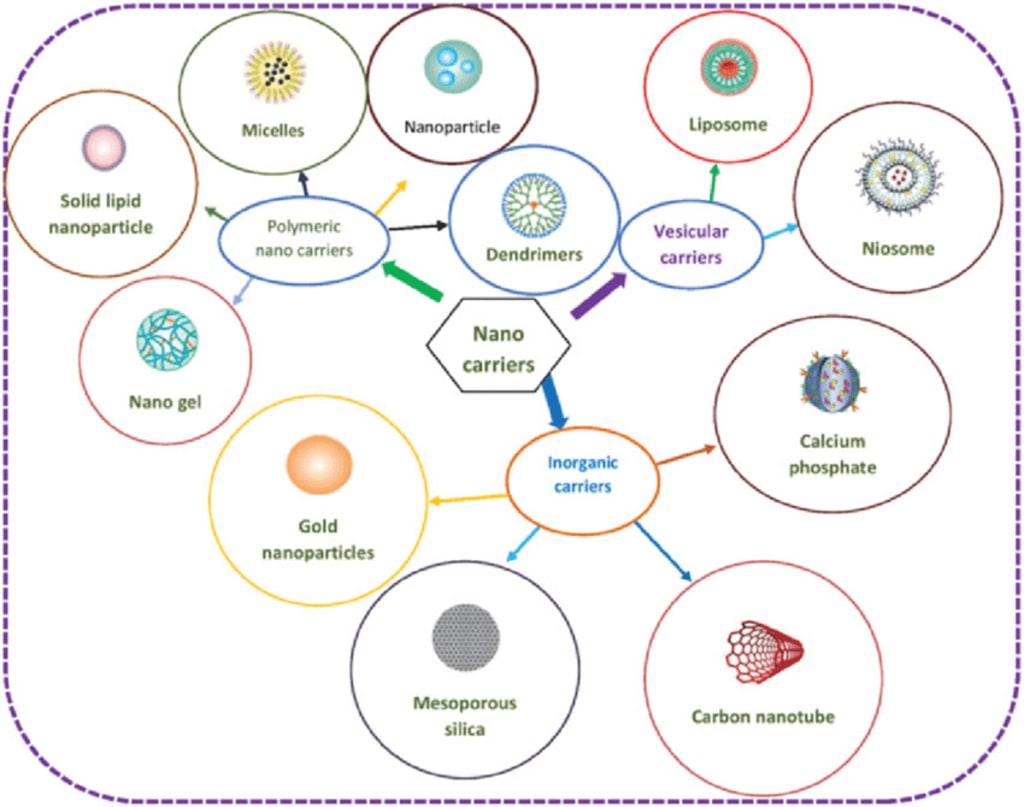

Types of nanocarriers

Virus based and natural nanocarriers, passive and active mechanisms

Virus based nanoparticles:

VNPs, or virus-based nanoparticles VNPs, also known as virus-like particles (VLPs), are uniformly shaped, self-assembled nanosized (about 100 nm), strong protein cages. These viruses come from a variety of sources, including plants (cowpea chlorotic mottle virus [CCMV], cowpea mosaic virus [CPMV], red clover necrotic mosaic virus [RCNMV], and tobacco mosaic virus [TMV]), insects (flock house virus), bacteria (MS2, M13, Q), and animal viruses (adenovirus, polyomavirus). VNPs, an emerging nanocarrier platform, have a number of appealing qualities, including as morphological homogeneity, biocompatibility, and simplicity in surface functionalization.

Figure

Structure of VNPs.

Abbreviation: VNP, virus-based nanoparticle

Drugs can either be chemically or physically bonded to the surface of VNPs for drug delivery applications. The drug payload is loaded into VNPs during physical entrapment using the straightforward and uncomplicated supramolecular self-assembly/reassembly of viral protein capsid. While in the chemical attachment, drug molecules are covalently attached to certain (naturally occurring or designed) reactive spots on the capsid proteins to load drug cargo onto VNPs. VNPs can be used as drug-delivery nanocontainers to target specific cancer targets by either taking advantage of some viruses' natural affinity for receptors that are overexpressed in different tumour types, such as the transferrin receptor (TfR), or by chemically or genetically altering the exterior surface of virus nanocarriers.

Natural nanocarriers

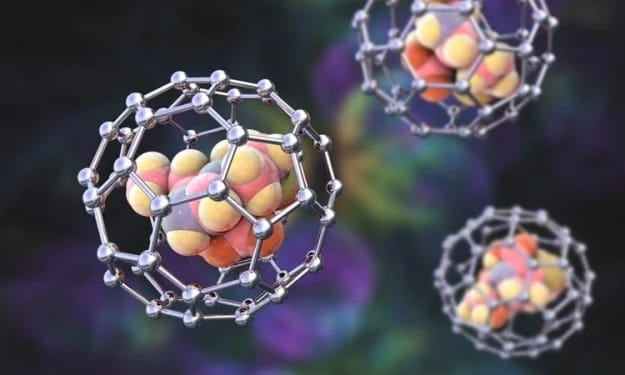

Iijima59 made the discovery of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) in 1991. CNTs are nanoscale, hollow, tube-like arrangements of carbon atoms. CNTs are made by wrapping up graphene sheets into a tube-like shape and are a member of the family of fullerenes, which is a third allotropic form of carbon.Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), which are created by rolling up a single graphene sheet, and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), which are created by rolling up multiple concentric graphene sheets into a tube-like structure, are two different types of 60 CNTs (Figure 7A and B). CNTs can extend over a thousand times longer than their diameters and have cross-sectional dimensions in the nanoscale range. SWCNTs and MWCNTs typically have outside diameters between 0.4 and 2 nm and 2 and 100 nm, respectively.

Figure

Graphical representation of SWCNTs (A) and double-walled CNTs (B).

Abbreviations: CNT, carbon nanotube; SWCNT, single-walled carbon nanotube.

On nanocarriers, focusing mechanisms and surface functionalization

Passive device:

Because tumor-bearing blood arteries are leaky by nature, nanocarriers can easily pass through the endothelium barrier and enter the interstitial space. The size of the tumour endothelial cell linings vary depending on the type of tumour and ranges from 100 to 700 nm, which is 50–70 times larger than the typical and distinctive endothelium (up to 10 nm). Furthermore, solid tumours have a weak lymphatic drainage system; as a result, the extravasated molecules do not receive proper circulatory circulation, which results in the accumulation of nanocarriers at the tumour site. This phenomenon is known as the EPR effect, and it is thought to be a fantastic strategy for tumour targeting.

However, due to the diffusion phenomena, nanocarriers containing low molecular weight medications must reenter the bloodstream in order to remain at the tumour site for a longer period of time. The targeting impact of such medications is referred to as "passive targeting" and is entirely dependent upon the pathophysiological and immunochemical properties of the tumour tissues.

Active mechanism:

With the use of a site-specific targeting ligand, the surface of nanocarriers can be modified to actively target particular tumour tissues. Small molecules, antibodies, antibody fragments, glycoproteins like transferrin, vitamins like folic acid, growth hormones, and nucleic acids are some of the targeting agents frequently employed to improve the site specificity of nanocarriers. In addition to reducing the off-target delivery of chemotherapy drugs, active tumour targeting also helps patients avoid the limitations of passive tumour targeting and overcome multiple drug resistance. The chosen targeting moiety must exclusively bind to a receptor that is overexpressed by tumour cells solely for the active targeting technique to be effective. The desired target receptor must also be uniformly expressed in all target cells.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.