The People’s Right to Choose Their Leader

Why a Third Trump Term Would Reflect the Founders’ Intent

When the framers wrote the U.S. Constitution, they deliberately refused to limit how many times a president could serve. They placed their faith not in bureaucracy but in the will and wisdom of the people. Their logic was simple: in a free republic, authority must flow upward from the governed, not downward from government. For nearly 150 years that principle stood unchallenged, until one president broke the custom and the nation followed him willingly.

---

Washington’s Example: Power as a Trust, Not a Throne

George Washington could have ruled for life. He was universally admired, unopposed, and seen as irreplaceable. Yet after two terms, he stepped down voluntarily. He wanted the presidency to remain a temporary stewardship, not a permanent throne. His restraint created an unwritten rule: two terms by choice, not by force.

For generations, presidents honored that example out of moral conviction rather than legal coercion. The system worked because virtue and accountability still governed the office.

---

The Founders’ Reasoning: Hamilton on the People’s Right to Reelect

In Federalist No. 72, Alexander Hamilton warned that denying voters the right to reelect a president would damage both government and liberty. He wrote:

“Nothing appears more plausible at first sight, nor more ill-founded upon close inspection, than a scheme which would render the magistrate ineligible after a certain period.”

Hamilton’s reasoning was clear. Fixed limits would remove incentives for good behavior, waste hard-earned experience, and “deprive the people of the opportunity of continuing in office those who have given them satisfaction in the execution of their duties.”

To Hamilton, the ultimate safeguard against tyranny was public consent, not legislative restriction. The founders trusted free citizens more than arbitrary limits. They designed a republic rooted in virtue, not a system of forced turnover.

---

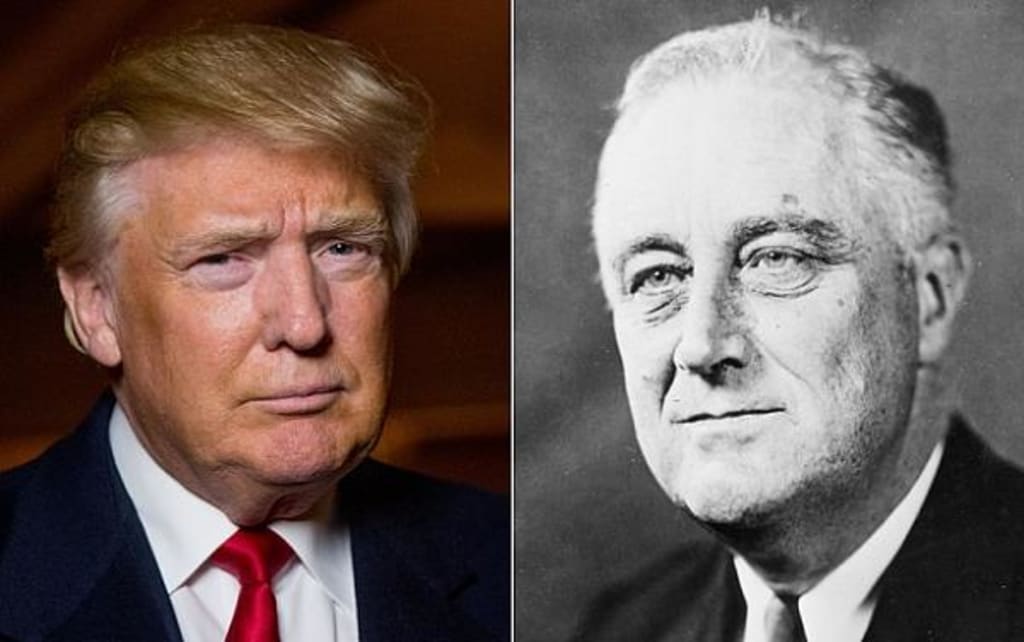

FDR’s Four Terms: Crisis, Continuity, and the Public Mandate

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency tested that faith in democracy. When he first ran in 1932, the nation was collapsing under the Great Depression. Banks had failed, unemployment neared 25 percent, and families were losing their homes. Americans turned to him out of desperation, not because he sought power but because he offered direction.

He won again in 1936 by one of the largest margins in history. By 1940, Europe was engulfed in war, and many Americans believed that switching leadership mid-crisis would risk disaster. Roosevelt agreed to run a third time, arguing that continuity in leadership was vital for national survival.

After Pearl Harbor, with the nation in total war, he ran again in 1944. His victory was not a coup; it was the will of the electorate in extraordinary times. His four terms did not betray democracy. They exemplified it. The people retained the power of choice at every stage. His service until death in 1945 demonstrated the strength of consent, not the weakness of the Constitution.

---

The 22nd Amendment: A Reaction, Not a Principle

Roosevelt’s long tenure frightened many in both parties after the war. Lawmakers feared that a less noble leader might use popularity to entrench himself permanently. So in 1951, Congress passed the 22nd Amendment, limiting any president to two elections.

The wording is precise:

“No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice.”

The amendment restricts the act of election, not the service of office. It does not forbid a president from succeeding by appointment, succession, or emergency. Nor does it erase the founders’ intent that the people remain the final arbiters of leadership.

The spirit of the amendment was not to weaken democracy but to guard against monarchy—against hereditary or perpetual rule without consent. The concern was an unelected ruler for life, not a freely chosen leader returning when the people demanded it.

---

Modern Parallels: Then and Now

FDR’s time was defined by crisis—economic collapse, global war, and moral uncertainty. Today, the United States faces crises of a different but equally grave nature:

1. Government corruption and the loss of public trust

2. Massive economic instability, with inflation, debt, and shrinking opportunity

3. Cultural and moral division threatening national unity

4. Erosion of liberty through censorship, bureaucratic overreach, and weaponized institutions

The crises of our time are not foreign armies or collapsing banks but corrosion from within: spiritual, moral, and institutional decay. In such moments, continuity of proven leadership may again become not only desirable but necessary.

The same reasoning that justified Roosevelt’s extended service could, in principle, justify it again. If the people, facing instability and distrust in government, choose a leader who has already proven capable of commanding national confidence, the founders’ design allows for that will to be heard.

---

Constitutional Paths Still Open to the People

Even under current law, several constitutional mechanisms preserve the possibility of continued service by public consent:

1. Repeal or Modify the 22nd Amendment

Article V allows the people, through Congress and the states, to change their governing rules. It is difficult, as it should be, but it is entirely lawful.

2. Succession Through the Vice Presidency

The amendment forbids a third election, not service by succession. If a former president were to become vice president and later assume the presidency upon a resignation, courts would need to decide whether “cannot be elected” equals “constitutionally ineligible.” The text leaves that question ambiguous.

3. Succession Through the Speakership or Other Roles

The line of succession places the Speaker of the House next in line after the Vice President. Nothing in the Constitution forbids a former president from serving as Speaker and assuming office in a crisis.

4. Advisory or Acting Service

The Constitution does not prohibit a former president from serving in other executive capacities that influence national direction. The 22nd Amendment limits elections, not leadership.

Each route would face political resistance and judicial review, but none contradicts the plain text of the Constitution. The letter of the law still leaves the people’s sovereignty intact.

---

The People Remain the Final Authority

The founders built a republic of consent, not permission. The Constitution is not a cage; it is a covenant. It limits government, not the governed. If the American people overwhelmingly choose a leader to return, even for a third term, and they do so through lawful means, that act would not defy the Constitution but fulfill it.

As Hamilton argued, preventing the people from reelecting the leader they trust “deprives them of the opportunity” to continue in office those who have served them well. Washington’s humility established an example, not a command. Roosevelt’s four terms proved that the people’s will can rightfully transcend custom. The 22nd Amendment, written in reaction to one era, cannot erase the founders’ original intent: that the people are sovereign, and their right to choose is supreme.

---

Conclusion: Liberty’s True Safeguard

The fear that led to the 22nd Amendment was fear of a crown, not of the ballot box. America was never meant to be ruled by permanent families, but neither was it meant to deny its citizens the right to recall proven leadership in perilous times.

The founders trusted the wisdom of free men and women to know when change was needed and when continuity was essential. If, in the face of modern crises, the American people once again unite behind a familiar leader—and if that will is expressed lawfully and openly—such a choice would not betray the Constitution. It would honor the founding principle that the power to govern belongs always, and only, to the people.

---

Editor’s Note

This analysis does not advocate a specific outcome, but rather it examines the constitutional and historical reasoning behind claims about term limits and leadership continuity. It seeks to clarify what the law says, what the founders intended, and how the principle of consent remains central to the American idea of self-government.

About the Creator

Peter Thwing - Host of the FST Podcast

Peter unites intellect, wisdom, curiosity, and empathy —

Writing at the crossroads of faith, philosophy, and freedom —

Confronting confusion with clarity —

Guiding readers toward courage, conviction, and renewal —

With love, grace, and truth.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.