The Life and Impact of Hugh M. Browne

A Legacy of Innovation and Uplift

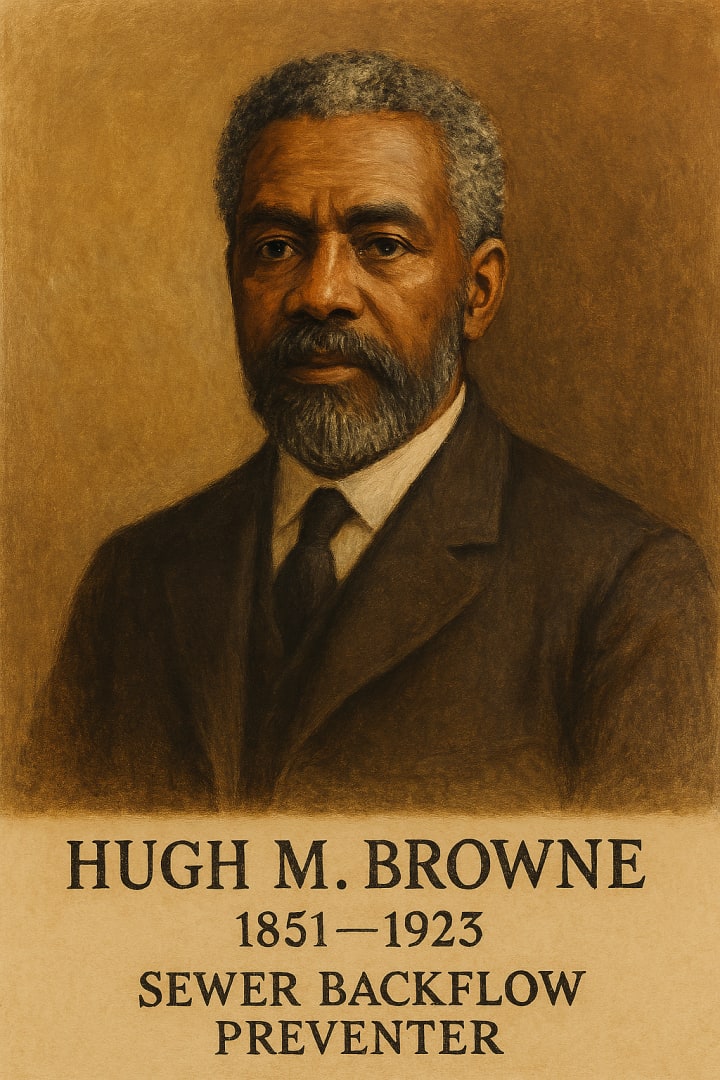

WASHINGTON, D.C., 1923 In an era defined by both oppressive barriers and extraordinary breakthroughs for African Americans, one educator‑inventor stood at the crossroads of civic progress, public health, and educational reform. Hugh Mason Browne — born June 12, 1851, in Washington, D.C. — dedicated his life to elevating living conditions and broadening educational opportunity for Black Americans. Though best remembered as a pioneering school leader and advocate of industrial learning, Browne also contributed meaningfully to public sanitation through a patented invention designed to stop contaminated wastewater from seeping into homes.

A Scholar Formed Amid Reconstruction Optimism

Browne grew up in a prominent free Black family in Washington, D.C., where the ideals of progress, education, and civic duty shaped his early environment. After excelling in the city’s segregated public school system, he earned a B.A. from Howard University in 1875 and later completed his theological and ministerial training at Princeton Theological Seminary in 1878.

Armed with both intellectual rigor and moral purpose, Browne traveled abroad for advanced study in Scotland and Germany, experiences that further expanded his sociopolitical worldview. His early academic path already reflected a signature trait: blending deep theoretical learning with a drive to solve real‑world problems affecting everyday people.

Champion of Practical Education and Social Advancement

Browne’s commitment to practical skills and industrial education became central to his philosophy. His work as a professor at Liberia College from 1883–1886 marked an early attempt to reform educational systems by shifting from purely classical learning toward skill‑based, hands‑on instruction. This approach aligned him with the emerging national conversation about the best strategies for empowering African Americans in the post‑Reconstruction era.

This ideology placed Browne in intellectual dialogue with towering contemporaries such as Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois. He participated in the **Committee of Twelve for the Advancement of the Interests of the Negro Race, a short‑lived but historically important effort to build unity among Black leaders seeking coordinated strategies for racial uplift.

Despite ideological differences among the group’s leaders, Browne managed to occupy a thoughtful middle ground — valuing Washington’s emphasis on vocational training while respecting Du Bois’s push for civil rights and classical education for future leaders.

Inventor of a Public Health Safeguard

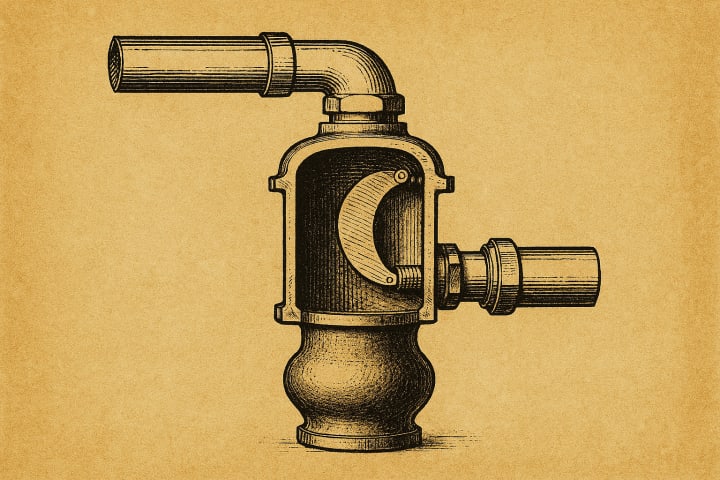

Beyond his academic leadership, Browne demonstrated a practical ingenuity reminiscent of Black inventors like Elijah McCoy and George Washington Carver. In the late 1880s, Browne turned his attention to an everyday but dangerous problem: contaminated wastewater backing up into residential cellars.

On April 29, 1890, he was awarded a U.S. patent for a device designed to prevent the backflow of sewer water into houses. The invention functioned as a protective barrier, improving sanitation and reducing the health risks associated with wastewater infiltration — a major public concern in densely populated urban neighborhoods of the 19th century.

Newspapers of the era later credited Browne’s device among notable inventions by African Americans, reflecting the broader contributions Black innovators made to everyday American life despite working under the constraints of segregation and systemic discrimination.

Leadership at the Institute for Colored Youth

In 1902, Browne became principal of the Institute for Colored Youth, today known as Cheyney University of Pennsylvania. His leadership transformed the institution. Viewing education as a means to dignified labor and upward mobility, he moved the school from Philadelphia to rural Cheyney to expand its facilities and align it with the industrial education model championed by Washington. He also established the Training School for Teachers, ensuring that Black educators would carry his instructional philosophy into classrooms across the country.

During his tenure (1902–1913), Browne strengthened academic programming while maintaining his unwavering focus on practical skill development a fusion that would influence American vocational training for decades.

A Legacy Rooted in Dignity, Innovation, and Uplift

By the time of his death on October 30, 1923, Browne had created a multilayered legacy: inventor, educator, theologian, civil rights advocate, and institutional leader. His life serves as a powerful reminder that innovation is not limited to laboratories — it can emerge from classrooms, communities, and the persistent pursuit of a better life for others.

His sewer backflow preventer may seem modest compared to grander technological feats, but like the man himself, the invention addressed a simple, essential need: ensuring safe, dignified living conditions for families. In both his educational work and his engineering insight, Hugh M. Browne helped build the foundations of a more “civilized living environment,” advancing public welfare at a time when such advocacy required extraordinary resolve.

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE FOR MORE STORIES

About the Creator

TREYTON SCOTT

Top 101 Black Inventors & African American’s Best Invention Ideas that Changed The World. This post lists the top 101 black inventors and African Americans’ best invention ideas that changed the world. Despite racial prejudice.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.