Black Holes: The Enigmatic Giants of the Cosmos

Black Holes: The Enigmatic Giants of the Cosmos

Black holes are among the most intriguing and perplexing objects in the universe, captivating scientists and the public alike with their extreme properties. These cosmic entities are not actual holes but regions where immense amounts of mass are compressed into an extraordinarily small volume, creating gravity so intense that nothing—not even light—can escape. This boundary, known as the event horizon, marks the point of no return, encapsulating all the matter within. While black holes remain invisible due to their light-trapping nature, their effects on surrounding matter and space-time provide crucial insights into their existence and behavior.

The concept of black holes dates back over 200 years, but their theoretical foundation was solidified in the 20th century. University of Chicago professor Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, at just 19 years old, calculated that stars exceeding a certain mass—about 1.4 times that of the Sun—would collapse into these dense objects after exhausting their nuclear fuel, a discovery that earned him the Nobel Prize in 1983 despite initial ridicule. Albert Einstein's general relativity further supported this, describing black holes as singularities where space-time curves infinitely. However, direct evidence was elusive until advanced telescopes like Hubble provided high-resolution observations of their gravitational impacts.

Black holes form primarily when massive stars die. At the end of their lives, these stars explode in supernovae, leaving behind cores that collapse under gravity, forming stellar-mass black holes roughly the mass of the Sun but only a few kilometers across. Others arise from neutron star mergers, as detected by LIGO and Virgo in 2017. Supermassive black holes, weighing millions to billions of solar masses, reside at the centers of nearly every galaxy, including our Milky Way's Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), which is about 4 million solar masses. Their origins are mysterious, possibly from the merging of smaller black holes or rapid growth in the early universe. Intermediate-mass black holes, ranging from 100 to 10,000 solar masses, bridge the gap but are rare and poorly understood, offering clues to supermassive formation.

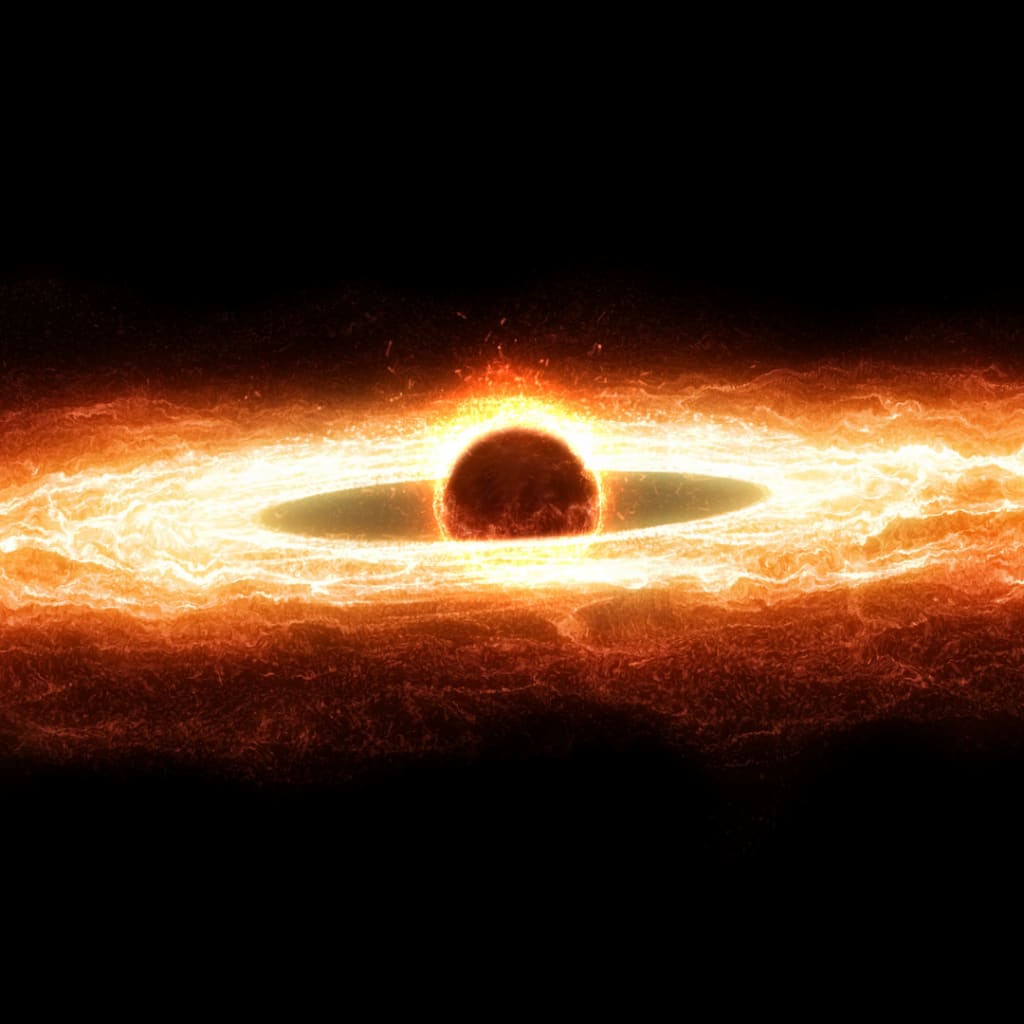

Detecting black holes relies on indirect methods, as they emit no light. Astronomers observe accretion disks—rings of gas and dust spiraling inward, heating up and emitting X-rays and other radiation. Gravitational effects on nearby stars, like those orbiting Sgr A*, confirmed its presence and earned the 2020 Nobel Prize for Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez. Gravitational waves from colliding black holes, first detected in 2015, reveal their masses and distances. Gravitational lensing, where black holes bend light from distant objects, aids in spotting isolated ones. The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) captured history's first black hole images: M87's in 2019 and Sgr A*'s in 2022, showing glowing rings of superheated gas.

Despite their complexity, black holes are remarkably simple, defined solely by mass and spin. They are compact: a solar-mass black hole's event horizon spans just 6 kilometers. All spin, with some like GRS 1915+105 rotating over 1,000 times per second. Matter approaching them undergoes "spaghettification," stretched vertically and squeezed horizontally. Supermassive ones act as particle accelerators, launching jets near light speed. Contrary to myths, they aren't cosmic vacuums or wormholes; their gravity mimics any object of equal mass from afar.

Hubble revolutionized understanding by linking black holes to quasars—intensely bright galactic cores powered by supermassive black holes accreting matter. Quasars, once thought isolated, reside in galactic centers, emitting jets thousands of light-years long. Hubble measured black hole masses up to 3 billion solar masses and showed larger galaxies host bigger black holes, implying co-evolution. This "unified model" views quasars, radio galaxies, and active galaxies as perspectives of the same phenomenon. Black holes influence galaxy formation, spreading atoms via jets and winds, boosting or hindering star birth.

Mysteries abound. Inside the event horizon lies a singularity—infinitesimally small and dense—where general relativity breaks down, requiring quantum gravity to explain. Stephen Hawking's work suggests black holes have temperature and evaporate over trillions of years, raising the "information paradox": is data lost forever? Why many galactic black holes, like Sgr A*, are dormant remains unclear. Black holes test physics extremes, aiding measurements like the Hubble Constant for universe expansion.

Black holes are ubiquitous: the Milky Way may harbor 100 million stellar ones, with billions of supermassive across the observable universe. Key facts include the closest (Gaia BH1, 1,500 light-years away), farthest (in QSO J0313-1806, 13 billion light-years), largest (TON 618, 66 billion solar masses), and smallest known (3.8 solar masses). Our Sun won't become one—it's too small—but if it did, planets would orbit unchanged, albeit colder.

As telescopes advance, black holes promise deeper revelations about the cosmos, from galaxy evolution to fundamental laws. They challenge our perceptions, proving the universe's most extreme phenomena hold keys to its greatest secrets.

References

"Black Holes, Quasars, and Active Galaxies." ESA Hubble, accessed August 28, 2025, https://esahubble.org/science/black_holes/.

"Black Holes." Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.cfa.harvard.edu/research/topic/black-holes.

"Black Holes." NASA Science, accessed August 28, 2025, https://science.nasa.gov/universe/black-holes/.

"Black Holes, Explained." University of Chicago News, accessed August 28, 2025, https://news.uchicago.edu/explainer/black-holes-explained.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.