Big What?: Presenting a Major Limitation to Big Bang Theory

T.J. Greer, DMgt (ip)

*AI assisted with grammar, syntax, and clarity.

Why are so many astrophysicists lying about being able to see thousands of galaxies when it’s clear, based on simple mathematics concerning the concentration of stars in this galaxy alone in relation to the area of the Earth’s sky, that's not true? Astronomers utilizing instruments such as the Hubble Space Telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope, the Very Large Telescope (VLT), and the Keck Observatory, as well as the researchers at Sloan Digital Sky Survey are committing academic fraud (with fake pictures and all). To add insult to injury, they also admit to manipulating the colors of their already fake pictures. This would be comical if their fake data wasn’t one of the key pieces of evidence for the Big Bang, an already bizarre idea. Before I get into math that an Ivy League physicist would obviously have to respect. Let’s explore a common sense visualization.

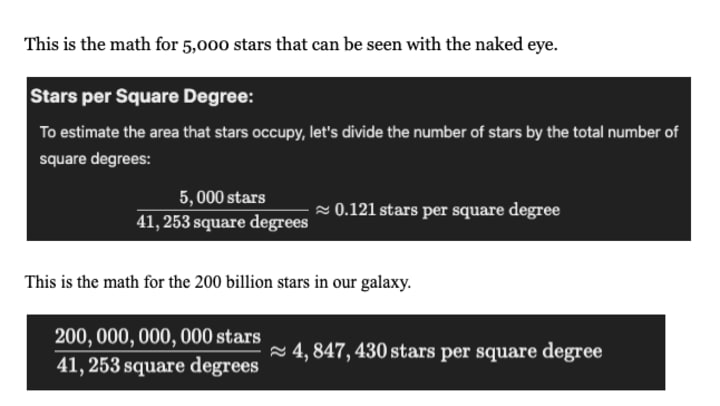

As of today, many astronomers claim they have taken pictures of thousands of galaxies. I have proved with some relatively simple math that they can’t. Look at the picture above. There are 200 billion stars in our galaxy that are observable with telescopes, but there are only about 5,000 stars in the sky that we can see with our naked eye (if you could see the entire dome). Now multiply those 5,000 stars that you can see by 20,000 million and it’s obvious that these astronomers, for reasons we may never know, are lying. It is obvious that they wouldn’t be able to see through the 100 billion stars that we could see with the most advanced telescope. In order for them to see thousands of galaxies, they would have to be able to see outside of this galaxy first, which I just showed that they can't. *Remember we can’t see the other 100 billion stars on the opposite side of the planet, so I had to use half for this part of the demonstration.

This is what Sloan claims: “The Sloan Legacy Survey covers over 7,500 square degrees of the Northern Galactic Cap with data from nearly 2 million objects and spectra from over 800,000 galaxies and 100,000 quasars.” This is now clearly a lie.

Moreover, humanity’s curiosity about the universe has long been fueled by the desire to understand the limits of our reach and knowledge. While we can observe countless stars in the night sky, our ability to see beyond our galaxy—the Milky Way—remains confined, as I have demonstrated. Understanding the proportions and distribution of stars within the celestial sphere offers insight into why observing stars outside of our galaxy is not feasible.

The Celestial Sphere: A Finite Perspective

The night sky can be likened to a vast celestial sphere, with a total area of approximately 41,253 square degrees. This spherical representation encompasses the entire visible sky, extending from the horizon above us to the zenith, all the way to the point directly opposite our location. While this sphere appears infinite in scope, it is, in fact, a finite structure. The visible portion of the sky we observe is limited to half the Earth’s surface—effectively the upper hemisphere of this celestial sphere.

Stars within this sphere are distributed across the sky in such a way that their density and brightness vary. The Milky Way galaxy, our home galaxy, contains about 200 billion stars, although estimates vary, ranging from 100 billion to 400 billion stars. While these stars are scattered over an expansive space, the vast majority are confined within the limits of the Milky Way, which itself is approximately 100,000 light-years in diameter. This leads to an important realization: when we look up at the night sky, we are seeing only a small fraction of the stars in the universe.

The Size and Distribution of Stars

If we assume that the 200 billion stars in the Milky Way are evenly distributed across the celestial sphere, we can calculate the amount of space each star would occupy on a miniature globe. By dividing the total surface area of the sky (41,253 square degrees) by the number of stars in our galaxy, each star would occupy a remarkably tiny fraction of the globe—about 6.28 × 10⁻⁹ cm². This is a minuscule area, far smaller than the size of a pinprick.

Given this incredibly small spatial distribution, the concept of observing stars beyond our galaxy becomes clearer. The stars we can see, even with the most powerful telescopes, are confined to our galaxy. While the stars themselves appear scattered across the sky, each one is essentially isolated in its tiny slice of space. The sheer vastness of space between individual stars—combined with their relatively even distribution within our galaxy—makes it extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible, to observe beyond the Milky Way using our current methods.

Hubble is Hobbling Now

Edwin Hubble’s contributions to the field of cosmology are often praised, particularly for his observations that contributed to the development of the Big Bang Theory. However, it is essential to critically examine the limitations of his work, specifically the statistical shortcomings of his sample size and the potential biases that shaped his conclusions. One of the primary issues with Hubble’s discovery of the relationship between redshift and distance in galaxies is that he relied on a sample size of only 24 stars, which, statistically speaking, is insignificant. To fully understand the implications of this limitation, we must explore the role of statistics in scientific discovery and how it affects the reliability of conclusions drawn in astronomy.

In any scientific field, sample size is a fundamental aspect of statistical analysis. A sample size refers to the number of observations or data points used to make generalizations about a larger population. In statistical terms, a larger sample size is preferable because it reduces the potential for error, increases the reliability of results, and allows for more generalizable conclusions. Hubble’s study, however, was based on a sample of just 24 stars—far too small a sample to represent the vast complexity of the universe. This sample size was insufficient to make statistically reliable claims about the nature of galaxies or the universe's expansion. Therefore, while Hubble’s conclusions were groundbreaking, they were not statistically significant, and his findings must be regarded with caution.

Another significant issue with Hubble's work is selection bias, a phenomenon where the sample of observed data is not random, but rather influenced by external factors that skew the results. Hubble's observations were likely focused on stars that were easier to detect or those that fit the hypothesis he was testing. Selection bias distorts the representativeness of the sample, making the conclusions drawn from it unreliable. In modern astronomy, this issue persists, as researchers often focus on galaxies within our local group or those that are closer and more visible, which limits the generalizability of their conclusions.

Despite these limitations, Hubble’s work contributed to the early development of the Big Bang Theory, which posits that the universe began as a singular point and has been expanding ever since. Hubble's observation of a relationship between the redshift of light from distant galaxies and their distance from Earth suggested that galaxies are moving away from each other, supporting the idea of an expanding universe. This observation formed the basis of the Big Bang Theory, which has since become a central tenet of modern cosmology. However, even today, physicists still face challenges stemming from insufficient sample sizes in their studies.

It is estimated that there are 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe, yet astronomers only have access to a small fraction of these galaxies. The most powerful telescopes, like the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope, while vastly more advanced than the tools Hubble had at his disposal, are still limited by the vast distances and the small portion of the universe they can observe. Thus, modern astronomers are still working with a limited sample, just as Hubble did, and cannot yet perform statistically significant studies about the entire universe.

Even if astronomers could observe outside of our galaxy, they would still be faced with the issue of sample size. To truly obtain a representative sample, they would need to study at least 10% of the 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe—approximately 200 billion galaxies. Given the technological constraints and the vast distances separating galaxies, such a large and representative sample is currently out of reach. As a result, modern astronomy suffers from the same statistical challenges that Hubble faced, leaving many of their conclusions about the cosmos statistically insignificant.

In conclusion, while Hubble’s discoveries were instrumental in shaping the early ideas of the Big Bang Theory, it is essential to recognize the statistical limitations of his work. His conclusions, based on a sample size of only 24 stars, were not statistically significant and suffered from selection bias. Today, even with more advanced technology, modern astronomers still face similar challenges due to the vastness of the universe and the limited sample sizes they can study. Furthermore, it is worth considering that what Hubble observed could have been star wobble, a natural motion caused by the gravitational pull of a star's planets or the deviations that occur as stars orbit the galactic center. “The reason for this [wobble] is simply the randomness of the materials from which the stars formed, and the tendency of objects to drift under their own inertia in nearly the same path for eons in the near-vacuum of space,” writes Dr. Baird of Texas A&M university. This stellar wobble may have contributed to the redshift patterns Hubble observed, rather than providing conclusive evidence of the universe's expansion. While Hubble’s work was pivotal, it is crucial to critically assess the statistical limitations and the ongoing difficulties modern astronomers face in drawing significant conclusions about the universe.

The Big Bang Theory, built on limited data and flawed statistics, undermines human psychological safety and spiritual development by presenting an impersonal, chaotic universe. It fosters scientific complacency, promoting inaccurate conclusions as fact, which can diminish trust in science and hinder genuine exploration of the universe's true nature.

Optional Reading: Further Thoughts on Stars.

While we have a good understanding of how stars orbit the center of our galaxy, the process is still an area of active research. The basic principles behind stellar orbits are well understood and can be described using Newtonian mechanics and general relativity.

Stars in a galaxy like the Milky Way follow elliptical orbits around the galactic center, primarily influenced by the gravitational pull of the galaxy's mass, including its supermassive black hole (Sgr A* at the center of the Milky Way). These orbits can be influenced by factors like the distribution of mass in the galaxy, the presence of dark matter, and interactions with other stars and gas clouds.

However, the details of how individual stars move within the galaxy and interact with other objects are still being studied. For example:

1. **Orbital Resonances**: Some stars might be in orbital resonances, where their orbits are influenced by interactions with other stars or structures like spiral arms or bars in the galaxy.

2. **Stellar Streams**: The motions of stars can also be affected by interactions with other galaxies or large structures within the Milky Way, resulting in stellar streams, where groups of stars follow similar orbits.

3. **Dark Matter Influence**: The exact distribution and role of dark matter in influencing stellar orbits remain an ongoing area of study. Dark matter likely makes up a significant portion of the galaxy's mass, but its distribution and effects on the motion of stars are not fully understood.

4. **Gravitational Effects of the Supermassive Black Hole**: The motion of stars near the supermassive black hole at the galactic center is particularly complex and requires relativistic models to explain their rapid movements. Observations of stars orbiting Sgr A* have provided insights into the behavior of matter in extreme gravitational environments, but there is still much to learn.

Overall, while we understand the general mechanics of stellar orbits, there are still many complex and nuanced factors influencing the motion of stars that require further investigation.

About the Creator

T.J. Greer

B.A., Biology, Emory University. MBA, Western Governors Univ., PhD in Business at Colorado Tech (27'). I also have credentials from Harvard Univ, the University of Cambridge (UK), Princeton Univ., and the Department of Homeland Security.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.