We are Wrong About How Mountains Form!

We think we know how mountains form

Funny thing about science. Sooner or later, you have to provide some evidence that whatever you’re going on about is actually true. Take plate tectonics. We’ve gotten pretty good at using this model to explain how the movement of Earth’s plates can create things like mountains on the surface. Except, it’s hard to test whether we’re actually right, because plate tectonics happens really, really slowly. But a study in the Calabrian mountains of Italy has come up with some of that “evidence” stuff and revealed that things might not always be as simple as we imagine them to be. We might be totally wrong about how mountains form.

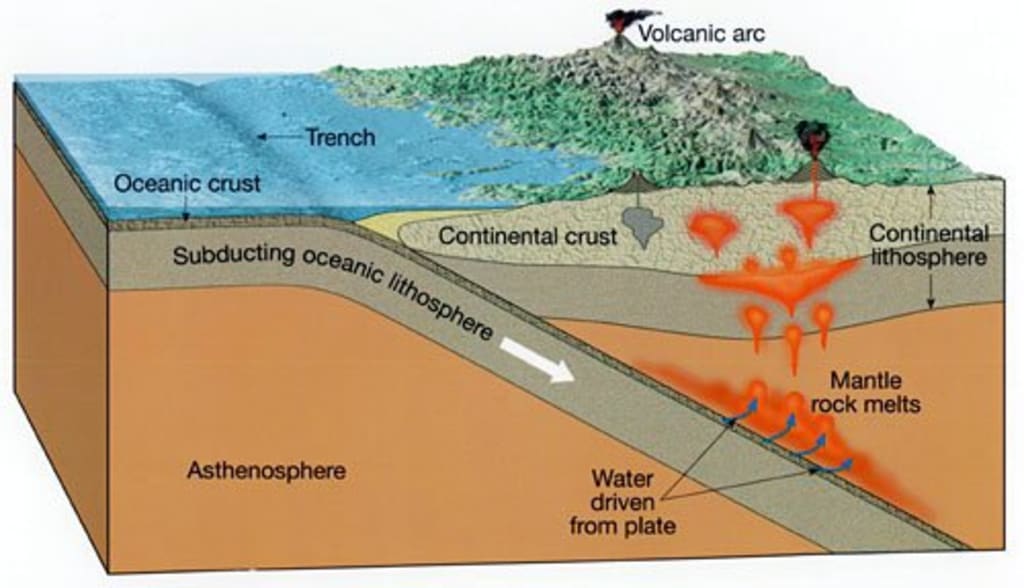

Plate tectonics is controlled to a great extent by powers we can't see. A couple dozen kilometers underneath the surface, the World's mantle streams in tremendous convection ebbs and flows, a piece like a dish of bubbling water. It's warmed from the planet's profound inside, which makes tufts of warm material ascent up towards the surface, prior to fanning out, cooling, and sinking back to begin the cycle once more. Furthermore, by all accounts, cold and unbending structural plates making up the outside are moved back and forth around like floaty toys on a pool. Not that your pool is at any point loaded up with bubbling water, I trust, however… you understand everything. At the point when the structural plates meet or veer, they structure emotional scenes like crack valleys, volcanoes, and mountain chains. It's sort of natural that mountains are assembled when plates impact. Picture the main edge of a mountain range, framing where one plate is subducting underneath another. The top layers of sedimentary rocks are scratched off and stack up, a piece like the ice scratched off your windshield. And all that thickened outside layer behaves like an icy mass made of rock, drifting on the liquid mantle under. Assuming all that is valid, the quicker the plates impact and thicken the hull, the quicker the mountains will ascend. So in the event that we could gauge mountain-building velocity and contrast it with how quick plates impact, we could test that model. The issue is, most structural plates move at about similar speed as your fingernails develop, and mountains require a long period of time to stack up. So it's staggeringly difficult to test our suspicions in fact. Dislike we can sit before them with a stopwatch to contrast their development and the pace of impact. In any case, in a paper distributed in Nature Geoscience in June 2023, researchers have thought of an imaginative better approach for remaking past paces of development, by perusing the actual scene. The review is centered around the 'toe' of southern Italy, where the Calabrian mountains have been framed by the African plate colliding northwards with the Eurasian plate. Specialists from the US have joined a few different geographical ways to deal with decipher the shape and geography of the scene. They involved proportions of radioactive components in the stones to resolve their ages, and afterward deciphered the actual shapes and elements of the mountain rocks to sort out where they were the point at which they framed. Together, this assisted them with sorting out the speed of subduction as well as the timing and speed of mountain working over the last 30 million years. For instance, compliment portions of the mountain landscape were framed when rock inspire was slow, though more extreme segments recommend quicker paces of elevate. What's more, the hints of streams chopping down through existing rocks show when rises changed rapidly too. Eventually, these various lines of proof showed that the Calabrian mountain building wasn't predictable over the long haul, yet was more stop-start. Also, shockingly, the paces of inspire were not steady with the pace of subduction of the African plate. At the point when subduction was quick, inspire was slow, and when subduction rates eased back, the elevate was quick. This is something contrary to what we'd anticipate from our straightforward models of structural crustal thickening. The outcomes propose that for this situation at any rate, mountain building is more than shallow, and the analysts have needed to find one more hypothesis for how the Calabrian mountains were inspired. Recollect those convection flows? Their thought is that the piece of the African plate that has been subducted under Eurasia effectively influences how the mantle under convects, and that this thusly influences the height of the outside. It's known as unique geology, and something's been recommended in PC models, yet previously unheard of in nature. It works like this. As the African plate plunges, it hauls a portion of the mantle down with it, and this descending stream is sufficient to set off another convection current to shape in the upper mantle. Mantle material streams down close to the subducting chunk, and is warmed and gets back to the surface some distance away. In any case, this lively downwelling of the mantle close to the subduction zone actually sucks the entire of the covering downwards around here, and sufficiently it's to balance and counteract any elevate that occurs because of crustal thickening. So subduction is quick, however inspire is slow. However, this present circumstance doesn't continue always. In the end the piece of covering hits a progress zone in the mantle, at around 660 kilometers down. Underneath this, the lower mantle is a lot denser, and the gulped hull only sort of sits on top of it. Subduction eases back, and ultimately the piece crumbles and removes, which upsets that incredible convection and downwelling. Without the attractions from the mantle and the heaviness of the section, the outside layer can return quickly up. Inspire is currently quick, despite the fact that subduction and real crustal thickening have eased back. So while the essential thought is staying put, it appears to be there's something else to this plate structural story besides we initially thought. The crustal plates aren't simply pushed around on top of a stirring mantle, however can change what's happening under too. What's more, this thus winds up changing how and when the highlights on a superficial level are constructed. There's more work to do to see whether this interaction is exceptional to these mountains, or happens from one side of the planet to the other. What's more, the creators trust that their new methodology will assist with remaking mountain-assembling somewhere else. Yet, this study shows us that the Earth is a more convoluted interdynamic framework than we recently envisioned, in which those rough pool floaties can change the circumstances in the actual pool. Furthermore, better comprehension how and why mountains have developed assists us with all the more precisely sorting out our planet's set of experiences, and with it the historical backdrop of basically everything.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.