Volcanoes may be hidden deep within Europa, raising chances of it hosting alien life

A volcano may be hidden in the depths of Europa

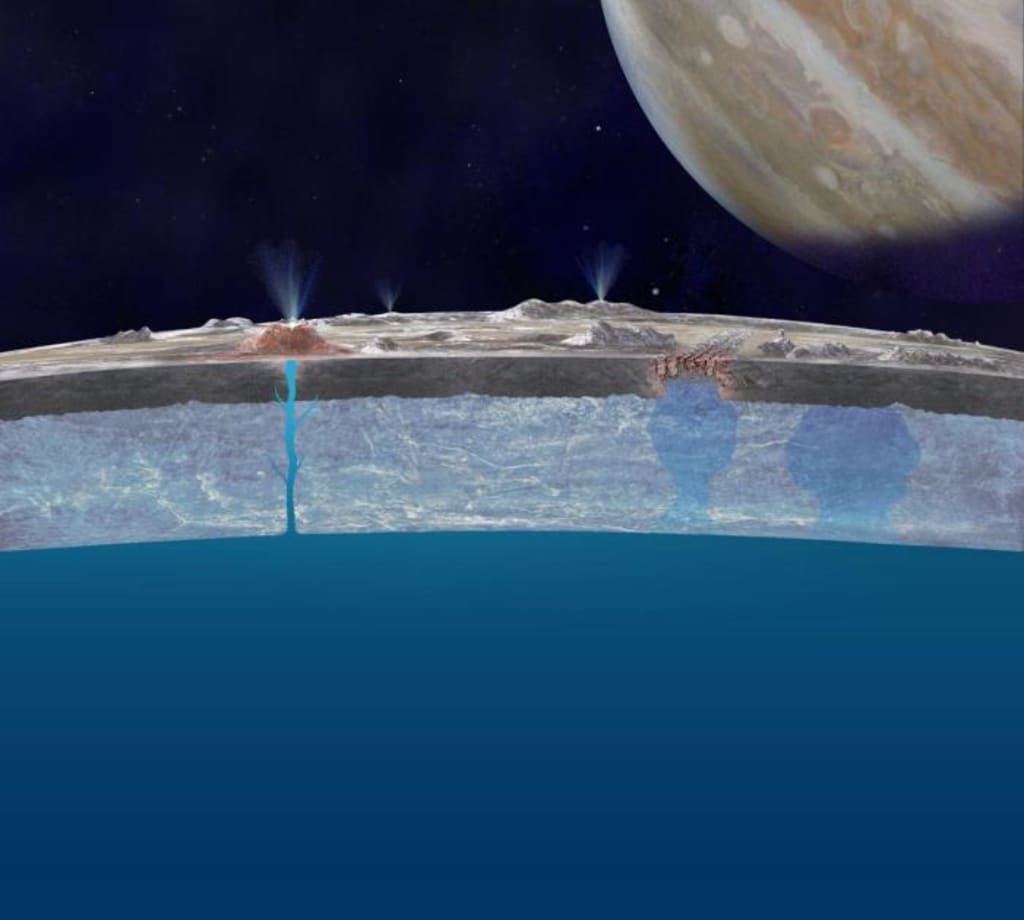

Jupiter's icy moon Europa is increasingly becoming the best place in the solar system to search for alien life. New models suggest that the rocky mantle beneath thick ice and the Aral Sea may actually be hot enough for volcanism. And, likely for most of its 4.5 billion-year lifespan.

The discovery directly affects life lurking on the ocean floor of Europa.

"Our findings provide further evidence that Europa's subsurface marine environment is suitable for life," said geophysicist Marie Běhounková of Charles University in the Czech Republic.

"Europa is one of the rare planetary bodies that has maintained volcanic activity for billions of years, and may be the only planetary body other than Earth with a large reservoir and long-lived energy source."

You might think that an icy world is a far cry from the life-sustaining warmth of the sun, where surface temperatures tend to peak at -140 degrees Celsius (-225 degrees Fahrenheit), so finding living organisms is unlikely, but in reality There is precedent for this on Earth.

Yes, most life here does depend on a food web based on photosynthesis...but in some extreme environments (without sunlight) life has been found in another way.

In the dark depths of the ocean, too deep for sunlight to penetrate, the volcanic vents seep heat into the surrounding waters. There, life is built on chemical synthesis, and bacteria use energy from geochemistry instead of solar energy to produce food. Other organisms that accompany the bacteria can eat them, creating an entire ecosystem in the dark.

We know that Europa harbors a global ocean beneath a thick crust of ice - we've seen liquid water spewing out of cracks in the ice in geysers, and we've detected salt. This answers some of the conditions for chemically synthesized hydrothermal life as we know it.

We don't know if Europa has volcanic activity below its seafloor and is open to life like a crater on Earth.

It's possible that Jupiter's moon Io is the largest volcanic world in the solar system, due to the constant pressure that Jupiter's gravity (and that of other Jupiter moons) keeps heating its interior.

However, because Europa is farther from Jupiter than Io, there are still doubts -- so Behonkova and her colleagues decided to try to solve this problem.

They used detailed models to simulate the evolution and heating of Europa's interior. They found that several mechanisms may be at work to prevent Europa from freezing completely.

First, the heat released by the radioactive decay of elements in the mantle may have contributed to a significant portion of the heat inside the moons, especially in early Europa.

Over time, though, the changing stresses from tidal forces exerted by the moons' elliptical orbits around Jupiter should have created a constant curvature inside Europa.

This bending, in turn, generates heat -- and there should be enough heat to melt the rock into magma, leading to volcanic activity that could be happening today, especially at high latitudes near the poles.

The simulations give scientists a signal of this activity, looking for missions such as NASA's Europa Clipper and ESA's JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) missions, which launch in 2024 and next year, respectively. ) and wait for the probe to come in close contact with Europa.

Gravitational anomalies may indicate deep magmatic activity, while the anomalous presence of hydrogen and methane in Europa's thin atmosphere may be the result of chemical reactions taking place at hydrothermal vents. Fresh marine material deposited on Europa's surface may also indicate subsurface activity.

"The prospect of Europa's seafloor heat, rocky interiors and volcanoes raises the possibility of Europa's ocean being a habitable environment," said Rob Pappardo, a Europa Clipper project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who was not involved in the project. NASA Clipper Project Scientist Robert Pappalardo said.

"It's an exciting prospect that we might be able to test this with gravitational and compositional measurements from the Europa Krapper program."

But first, we'll have to wait a few more years for the spacecraft to get there.

About the Creator

suzanne darlene

Take you to understand scientific knowledge

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.