The components of a poor concept

The time spent coming up with terrible ideas.

The components of a poor concept

The time spent coming up with terrible ideas.

I made a mistake. I'll tell you about all the awful ideas, though, rather than just one. I'll generalize to a pattern that many concepts, both positive and negative, adhere to. I hope you — yes, you — will find this activity entertaining or useful. Otherwise, it wouldn't be my first poor decision.

What is an idea?

I'm implying that "idea" refers to problem-solving techniques. In my opinion, such are often abstract ideas that need to be mathematically modeled in order to resolve technical issues. The need for individuals, especially scientists, to be more transparent about their flawed theories and unsuccessful experiments is a secondary reason for writing this. But I want to stress that "bad" is actually excellent before this all starts to sound too gloomy!

Adverse outcomes

Admitting failure is rarely liked by people. It should come as no surprise. There are several social and psychological reasons not to. However, it is evident from sayings like "fail fast, fail often" that failure is a necessary condition for success. Of course, success is ultimately determined by how one fails and iterates, not by failure in and of itself.

If a study in science fails to identify a relationship between experimental variables, it is considered a failure. We refer to these as null or negative outcomes. The majority of scholarly publications do not allow the publication of negative results. This has to do with the notorious p-value.

The p-value of a result is, in general, the likelihood that the result was obtained by chance. It goes without saying that smaller is better, but the precise statistical interpretation is nuanced and has been the focus of several debates over the past ten years, sparked by the so-called reproducibility issue.

Until recently, a p-value of 0.05 was considered "statistically significant" in social science and medical studies. Numerous people have argued that 0.005 is a better suitable criterion and that this arbitrary one is insufficiently strict. A p-value of 0.003 is required in high-energy particle physics to report "evidence" of a particle, while a p-value of 0.0000003 is required to announce a "discovery." Others support going completely beyond the p-value. More broadly, rather than attempting to redefine what "significant" means, there have been several requests in the blogosphere and science magazines for scientists and, more significantly, scientific publications, to disclose negative results.

may be causing these unfavorable outcomes?

There are several accounts of tainted samples, inadequate data, subpar methods, and so on. What is a "bad" idea? All right, then, let's begin with unsuccessful trials. However, what about prior to the experiment's completion? All those poor ideas—what about them? Do we still need to report on those?

For instance, in theoretical physics, a terrible notion has no experimental evidence to support it. Of course, some poor concepts, like the planet Vulcan, fail spectacularly. However, most terrible ideas are not promoted to the public. This leads us to the precise definition of a "bad" or "failed" notion, which I will promote with humility rather than arrogance.

When we describe a concept as "bad," we are not passing judgment on the person who came up with it. Simply put, a terrible idea is one that does not turn out as planned or anticipated. Clearly, a lousy concept is disappointing. In contrast to unfortunate circumstances over which we have no control, a terrible idea is one that we can learn from, and how we respond to such setbacks will decide how successful we are in the future.

Therefore, if we can use a "bad" concept to create the next awful idea—which should be a bit less bad—it is actually a wonderful idea. It's not that horrible, is it?

Coming up with an idea

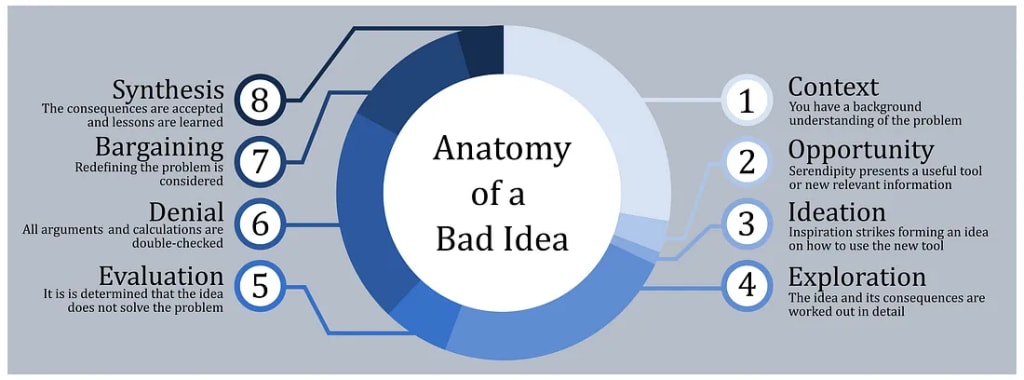

I will divide the brainstorming process into two stages. The first is where concepts are developed and assessed. This will describe the process by which all ideas—both good and bad—are created.

Background

Problems are solved via the generation of ideas. Therefore, we need to have some knowledge about an issue before we can come up with an idea. This creates the idea's context. We accumulate issues or queries throughout our life. A few are little. Some are large. In the back of our brains, these queries provide the framework for ideas to emerge.

Typically, scientific concepts relate to "big" questions. A possible answer to a scientific problem is what we mean when we discuss an idea that a scientist could have. Scientific challenges vary widely in size. Determining the relationship between chocolate and Nobel awards is almost irrelevant, but identifying and mitigating the consequences of climate change is a major challenge. Most, if not all, scientists spend their time resolving minor issues. This is due to the fact that complex issues are decomposed into more manageable difficulties. In contrast to what Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs portrays, no scientist is actively addressing climate change. Because humans nearly always adopt "small" remedies to handle tiny issues, bad ideas are common.

The chance

It is impossible to will ideas into being in a vacuum. The appropriate instrument must be offered to us externally. Usually, this occurs by accident. In academia, ideas can originate from a variety of sources, chief among them being other scholars. We converse at the whiteboard or over coffee, read scholarly articles written by others, and attend their presentations.

Quite technical thoughts can occasionally arise from completely unrelated activity, like watching a movie, reading the news, or reading a blog. These possibilities are always available to everyone. So, is this essential step only a case of pure chance? No. We may develop two abilities to improve our chances of receiving information that will help us come up with ideas.

The first is to identify good settings and worthwhile possibilities. What suits one individual may not suit another. Let's say, for instance, that you utilize Bluesky. Although following Justin Beiber is unlikely to result in any worthwhile chances, it might be advantageous to follow authorities on a variety of pertinent subjects.

Finding the link between an issue you already know about and something that flashes in front of you is the second skill. Because science is so disjointed in its symbols, language, and style, this is more difficult to acquire. Nonetheless, this ability may be enhanced by having a cohesive narrative "written" in your native tongue that explains a subject. As new information becomes available, incorporate it into that narrative.

Concept

An idea is a speculative solution to a problem using a tool. An idea is only the notion that perhaps I can use X to solve Y. The concept serves as the link between a possible solution and an open inquiry. This is the "ah-ha" or "eureka" moment that scientists frequently talk about. Since concepts are often quite superficial, it is otherwise unremarkable. Determining if the concept is excellent or poor requires a lot of work.

Investigating

Working out the specifics of a proposal so that its merits may be assessed takes up most of the time. Before a concept to be properly assessed, it must be precise. One easy solution to my cutlery sorting issue could be to combine a fork, knife, and spoon. That seems interesting, but unless the term merge, for instance, is defined, the concept cannot be assessed. Is the knife end positioned in opposition to the fork end? What happens to the spoon? A tangible problem cannot be solved by a hazy thought. The most time-consuming aspect of the process is often working out the specifics of a concept (and all of its potential variations).

The grief process

We've now reached a fork in the road, if you will. The second route, which leads to more rapid success, is a magnificent one. That is how excellent ideas go. Our course will lead us into the abyss.

Assessment

It should be simple to assess an idea's fitness if it is well-detailed, however fitness is not always simple to compute. With the other phases of ideation, the mourning process in response to negative thoughts might occasionally create a little subcycle. An concept may seem poor because of mistakes made during the investigation phase. Usually, though, there are obvious clues that the concept is flawed. It is easier to assess a possible suggestion when the problem is well defined. It is eventually determined that the concept does not address the initial issue. However, this is just the start of a downhill cycle, and the faulty concept is not just thrown aside.

Denying

In the slim prospect that something went wrong, all figures and arguments will be reviewed again before the project is shelved. The first phase is to simply ignore the reality of the situation, which is similar to the Kübler-Ross model of psychological reactions to death and loss (the well-known "five stages of grief"). This is demonstrated in technical work by carefully reviewing all computations and reasoning that resulted in a negative conclusion.

Negotiation

Redefining the issue or the answer is the last straw to be grasped. This stage of the procedure is where really poor science may surface. Data may be modified if it is involved. A misleading connection in the data can also be used to reframe the issue as one that seems resolved. A faulty concept can be "salvaged" in a variety of ways. One imagines that "this idea and the problem could be tweaked and "sold" as a significant result if I thought about it hard enough."

Rather, by being honest about our poor ideas, we eliminate the feeling of a sunk cost. Although it doesn't solve an issue, it's intriguing, and it was helpful to understand why it doesn't work.

Synthesis

The concept is integrated into the framework for the subsequent challenge to be conceptualized. Bad ideas have the advantage of being the only way to fully comprehend a situation. Struggling through arguments not only compels one to immerse oneself in a specific issue, but it also promotes investigation in the often desperate pursuit of solutions. Indeed, a lot of information regarding frequently overlooked issues is discovered along the way to deciding that the notion is indeed a terrible one. These encounters expand the range of potential future ideas by contributing to our contextual awareness of issues in the field. By dissecting a terrible concept, we improve our knowledge, pick up new skills, and broaden our toolkit, proving that bad ideas are actually the best ones!

Teachings

What have we discovered here? First of all, I want to have communicated that, at least in terms of personal development, the most beneficial ideas are those that we usually label as terrible ideas—the ones that never get off the ground. The term "idea" has several definitions, and if we accept slang, the adjective "bad" has even more. Since it would be challenging to convey the intricacy of the ideation process, I have not provided a concise description of the term "bad idea."

Naturally, we are not talking about the foolish practice of jamming a fork in a power socket, but there is still a lot to learn from it. The typical false dichotomy of good and wrong is another way to think about terrible ideas. In the sense that we are never in possession of the truth, we are never right as scientists. We try to get less incorrect over time, at best. We are always incorrect, to use a euphemism phrase. However, the most successful scientists are those who make intriguing mistakes. In other words, they have a variety of poor ideas.

The premise here is that the more negative thoughts one has, the more rich the environment is for generating new ones. It takes time to develop a comprehensive framework of possible issues to resolve. Before they acquire the underlying knowledge needed to apply excellent or terrible ideas, some people (who will remain anonymous) need to complete many university degrees. Only when you need the clarity to express your views to others will all those great outcomes from faulty ideas become more apparent.

Therefore, I strongly advise you to write down your unsuccessful ideas in the same way that you would your great ones. The ideation process does not occur in a vacuum, which is the most crucial point concerning terrible ideas that has not yet been discussed. Conversation over coffee, lunch, and the occasional beer is where I explore and assess a lot of my stupid ideas. All of this may be summed up in the following advice. Look for a friend who asks insightful questions and enjoys coffee or ramen. Next, come up with some poor ideas.

About the Creator

Elegant

"Join us on a fascinating exploration journey of a topic that matters to you, where we present new ideas and inspiring insights that open new horizons. Read, enjoy, and share in this adventure!"

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.