Budhni

My tribal sister and her green mangoes

Budhni

(Inspired by true events)

“I don’t think like that. You should also stop.” – G. Jose

Crystal clear bird songs vied to wake me that morning, my first in the middle of the Dangi Jungles. Eyes were ready to launch into full-on engagement with the day but I bid them shut a little longer, my twin teacups…stay luv. I whispered.

It’s a practice, my music teacher and the first friend of my soul had lessoned me - “To sing, train your ears to listen”, he had said, “Listen to every sound when you are waking”.

A few strong chirps, some faint ones in the distance and a loud shrieky one, all creating a comforting symphony I could finally fold up in.

The dreamer in me gained full supremacy – to linger in the half-awake, half-asleep realms of dream worlds at the helm of a new day with its infectious activity, were moments I always found myself absorbed in. Always since he first let me in on this secret when I was only 15.

Little did I know in 2001 that on this first of several journeys, I was about to marry the one true love of my life – the beloved landscape of the “unknown” ready to embrace me in its gorgeously familiar arms and walk hand in hand into the horizon of mysteries.

Government forest rest house rooms promise to be small and so was mine. Since I had no idea what to expect, nor the bandwidth to register anything, my focus stayed uncluttered.

Thankfully the bathroom with its toilet was inside the room.

There I was - a weary mind and body laid flat on a clumpy cotton mattress with faint mustiness rising from it, an old three-blade fan rotating around its rickety axis looking down at me, both of us wondering, wondering something, not knowing what we were caught up in the wonderment of.

In this blissful moment, an entirely forgettable thing occurred with a swift strike to my mind which wanted nothing to do with agendas or purposes and so it lay forgotten until later when it rose like a Lochness Monster snorting at me with its toothless smile in my sea of change, squinting one eye “I told you so!”

I stirred myself awake eager to check things out in the morning light. Quickly bathed, brushed, got dressed, slipped an apple and a few things in my backpack and nearly stumbled outside. Scuffling into my shoes I stood on the veranda overlooking the jungle beyond my ground-floor room. I took in the cool of the morning while it swallowed me whole. Primeval romance ensued but I was still largely unaware.

I followed myself out through the corridor and quickly onto the road and kept walking until I reached the main road which had forests on both sides. Beckoning hills and trees standing at polite distances, interrupted by bushes, blur the picture effectively, the artist in me noted. Smiled somewhat.

6:00 a.m. The indigo light was now turning greyish blue softened by the haze rising from the trees. It was bound to get hot during the day, but did I think anything about that? Nope.

Oblivious to anything but the moment that was unfolding before me, I trod on. As if the deluge of thoughts allowed anything else. Not so aware that they had me snowed under and there was no way to escape. And yet, here I was, clearly a fine escape artist, so fine that she hadn’t registered the extent or the intent of her escape.

What is it about ‘innocence’ that begets memory to behave like a black hole?

My feet kept the better of me - rural nostalgia of a city girl from childhood memories of summer holidays in a similar dusty village of Saurashtra. My eyes bathed amply the brown and ochre landscape all around me. Shades of brown and yellow, grey with dots of green made by distant shrubs or the Mahua trees, all permitted ripples of expansion in my mind-body.

No sooner had the rhythm of walking set in, an urge to go cross-country rose. I started climbing the gentle slope of the hill. The natural undulations of the earth with its little rocks and pebbles created a sea below the soles of my feet.

I saw a group of 5-6 young boys coming down from my right. They soon crossed me with polite “Namaste” exchanged by both parties.

Nice. The sound of human voices to my ears. Different even. Maybe it was the setting that made the difference.

The hills dispersed our sounds as soon as they were heard, unlike in the city where they seemed to stick to the nearby electric poles or the road divider or some such place.

I climbed on.

My sight was magnetised towards a large Mahua tree in the distance above. Maybe because it was the only green thing from my vantage.

When I reach there, perhaps I should stop and sit under it and have that apple from my bag. I thought.

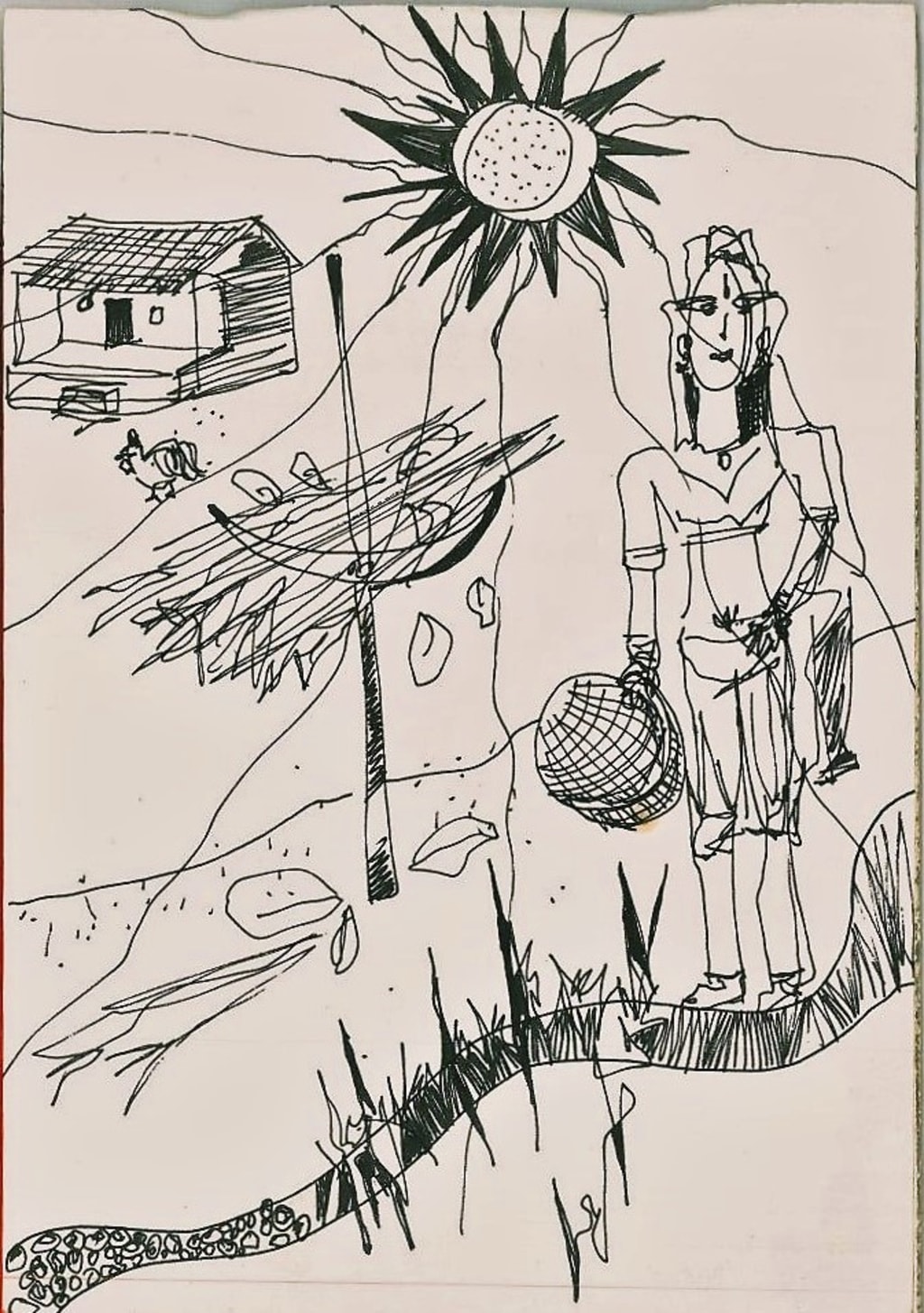

I reached the tree and found on my left a Dangi woman. Thin but strong, in her tribal attire, a saree tucked between her legs, a blouse of sorts, working on what looked like a field. The sun was glistening straight at us, making the sweat on her strong arms shine like glitter.

Weary, I sat down below the Mahua tree. Biting into my apple I found intrigue in her movements. She was picking up the dried twigs and branches laid by the side of the hill and climbing up with the bunch huddled on her shoulder to lay them down in the square patch of field.

I hadn’t ever had the opportunity or reason to watch closely how a field is prepared for sowing up until now.

No sooner had I taken my last bite than she had taken her 5th bundle up to her field one of the boys from that little party of young boys emerged from my left, almost unnoticed.

Namaste. Our eyes met.

Dressed in a regular shirt and pants. His hair was oiled and combed neatly with a side parting; a few strands had disobeyed that order. An intense look on his face opened out to words.

He greeted the Dangi farmer woman in their tribal dialect and had a quick conversation.

Then he turned to me and said, “I am wondering if I can ask you something.”

I looked around, fumbling for something in my bag wondering what this could be all about. I hadn’t expected to draw any attention to myself let alone be interrogated on my first conversation in the wild.

But there I was a 30-something city girl in off-white baggy pants with six pockets, a maroon Tibetan cotton full-sleeved shirt buttoned to my collar. My hair was tied in a tumbled-up bun with a scrunchy. A gold medallion on my neck, passed off as a mangalsutra helping me avoid questions like “Are you married” although I was.

Sure. Go on bhai. My gaze went past his shoulder then a little to a distance and back into my palms.

You see, that older man amongst us you met before, he is the priest of that temple up there. And pointed to the treetops above his right. He continued -

I asked him what is a city lady doing here in the jungles. And he said that you are “looking” for something. So, I was curious and wanted to know if you are indeed looking for something.

Ahhh. I relaxed.

I let my ‘ahhh’ linger between us aided by my smile. Partly to take time to think if I was indeed “looking” for something and what that could be.

It was clear now that I was indeed lost. I had no clue what my life was about, why was I the way I was and in fact who on earth was I. His simple question rounded it all up in a sweep, planting a sloppy full-stop of a sigh inside me, somewhere.

Lost.

With a sigh, I spilled my truth, “Yes, he is right I am looking for something.”

No sooner had I replied to him than I crossed my fingers in my mind hoping that he would not ask “What”.

I see. That is all he said and had another word exchange with the Dangi woman.

Instead, he asked, what are you doing here?

By this time bird book of Salim Ali had found its way into my hands and so I held it up and said, writer and an artist, yes, I am.

Which were both true though I was afraid it seemed like someone else’s job profile. Fake, I felt utterly fake.

Oh, and you are studying birds. He said, looking at the book.

I nodded.

A breathable silence followed leaving us to take it in.

Now it was time for me to ask a question.

What is she doing, can I ask? I pointed to the Dangi farmer.

His tone changed tempo. She is my aunt and she is getting her field ready. Those sticks she will burn those later to prepare her field for sowing.

I see.

The workers were supposed to come but no one has arrived so she’s working.

As if on cue something in me jumped to ask, and what does she pay the workers? I pressed.

Oh, it's always either Nagli Roti or Nagli Grain. He replied.

Nagli is the local term for the Ragi grain.

My eyebrows raised I pushed on eagerly. Watching her work had stirred a longing to get physical and into it myself. Body and I have had a love affair since I was little, however, what I didn’t know is that I was just signing up for a whole new relationship with it.

Ask her what she will pay me if I help her in the field.

That day was perhaps the first, that my Body’s mind leading its otherwise judgemental, analytical way, obscenely, unwittingly inherited from living the city life was about to get a fresh reboot.

He laughed and little wrinkles formed at the corner of his eye that was facing me.

He exchanged a few more with his aunt and scooted off, lest she rope him in to help her.

I got on with it.

Traipsing downhill I imitated my Dangi Sister, bundled up a few sticks and followed her uphill, laying them down beside her bunch. She burst into little giggles. Unbelievable. I think that’s what she thought.

The second, then the third and the fourth. I was enjoying my love of labour or labour of love. Around then, she came with a large wooden stick with a crossbow over it and gesticulated how to use it. Scoop the sticks and branches in it and hook the stick over your shoulder so one doesn’t need to hold them tight and get scratched in turn.

Neat.

After a few more rounds a clearer thought led my otherwise sombre inner mood. A part of me contested “Shouldn’t one be feeling more tired from physical labour? How come with each round up the hill, weighed by nearly 50 kgs on my shoulders I am only feeling more energised, happy even?”

Perhaps a city person would have contextualised it and offered labels like “meditative labour” or “mindful work” or some such concept.

In the middle of an experience, there is but that, the experience and one’s own, limited or otherwise understanding of it. To add any further meaning than what emerges in that very moment is a great disservice to the learning mind. It's simply a bad habit of overthinking. Thus, I overthought.

Was this my ‘experience’ and ‘understanding’ uniting in holy matrimony this morning beside a Mahua Tree, my Dangi Sister, the surreptitious priest leading the rituals of coming alive in something feebly mine own?

I knew now, somewhat, that thinking more than necessary was something to be greatly wary of.

On my 15th round perhaps, she could take it no more and pulled my hand. Before I could stretch out to pick up my backpack, she was dragging me downhill pointing to a village in the distance.

300 strides, and she still hadn’t let go of my hand.

Picture two little girls strolling down a park, hand in hand singing a tune in our souls. She may have picked up on my reverie and bent down to pick a tiny green mango. Peeling it with her tough field fingers while I looked on with a child's curiosity, she held it out for me to eat.

Biting in, the sour juices squinted my face into a smile that hadn’t felt this correct for a very long time. All the anguish and lostness to get to this moment suddenly fell away.

I bent down to imitate my earth teacher - picked another wee mango and peeled it to offer her so I could watch what it did to her face.

We smiled. Together.

She took me by my hand again and led me straight to her house. The dappled light under trees, the children looking on at a stranger in their village, the spider of memory web was now in the throes of it.

I felt like I was in a museum - admired, loved even.

Her home was just like her - sparse, strong, precise, and uncluttered. Mud walls of thatched bamboo, open, welcoming yet private, special. The mud chuhla, cooking pit was at the centre of the first room as you entered. The one on the left had a thatch platform fitted on branches to hold baskets full of vegetables and grains. Onion and garlic wreaths hung from the rafters in the ceiling. All walls had an opening before the roof began.

Sparrows tweeted in and out. The breeze could find us in any room through the same opening. It smelled of home. My body responded to it all by behaving as if it was mine too, I lived here too. Always had, always will.

The Outlaw outside was the drawing room. Open seating front porch. I sat myself down beside her entrance door, resting my back to soak in the cool from the mud wall behind. Looking out to the little ones shyly gathering to take a look at the new monkey in their zoo. My heart was full and getting fuller by the minute.

Emerging again Budhni bent down to hand me a plate with a big fat Nagli roti sitting plum in the centre and some red chillies covered with salt crystals.

Eat. She gestured.

I crossed my legs and put the plate on the mud floor, feeling the sanctity arise in me. Prasadam. Unexpected because well one tends to get lost in a moment and the obvious becomes a blessing, a miracle even.

I rubbed my hands, and rolled up my sleeves, making yum yum sounds to entertain for my little audience of children while I dived into my breakfast.

As I bit into my first bite the sentence that had flashed on my mind the first thing that morning came right back like a teacher banging on the blackboard.

“We shall earn our breakfast.”

That was the forgettable sentence that hadn’t forgotten to remind me of its presence.

My bite stopped midair.

Budhni shrugged, all ok?

I shook my head and smiled all her love right into me along with the Nagli Roti, her home and field, the wooden picking needle, and the mangoes, the children, the Otlaw it all went right in.

And have stayed.

***

About the Creator

Mithyajoj (penname)

Writing, for me, is an unapologetic exploration of self and everything else. A transformative encounter in early 2023 set the stage for an ongoing journey. Walk alongside me through the raw authenticity of my words, untamed and direct.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.