Knossos, Crete

The Aegean Sea,

2,500 BC

The body of the Minotaur was still cooling as Daedalus and Icarus ran down the passage. Torches flickered in crude bronze brackets as the slap of sandalled feet echoed across the walls.

“Hurry, my son,” panted Daedalus, “we must escape the Labyrinth before the King discovers what we have done.” He lifted the ball of string in his hand, feeling the thread running through his fingers as he ran. Somewhere behind them, they heard shouts and cursing echo off the rough stone. They kept running. They had been plotting their escape for months, ever since they’d helped Theseus escape from the Labyrinth. Daedalus had built the Labyrinth, at the command of King Minos, to house the Minotaur. As a young man, Minos had profaned and offended the gods by mating with a cow. The resulting abomination of their union, the Minotaur, had been banished to the Labyrinth, there to spend its pitiful existence skulking among the twists and turns of the maze. Shortly, there after, in one of his many wars with Athens, King Minos had decreed that the Athenians would send him seven young men and women every year, and they would be led into the Labyrinth one at a time and fed to the abomination.

Daedalus came to an intersection and stopped, listening carefully. He could still make out the shouting and cursing of the king’s soldiers somewhere in the Labyrinth. The maze was known play tricks on the ears of the unwary. Daedalus had designed the Labyrinth to do that. It played tricks on its victims, allowing the Minotaur to have fun with them first. Icarus almost ran into his father, who stood completely still, head cocked.

“Father?” whispered Icarus, “why have we stopped? The soldiers are gaining on-.”

Daedalus motioned for his son to be quiet. After another second or two he motioned to Icarus. “Come,” he whispered, “this way.” He turned down a side passage, then turned again. The sounds of their shouting and swearing noticeably faded. He made several more rapid turns in quick succession. After awhile, Daedalus stopped again. He heard nothing, but walked at a cautious pace. Daedalus crouched and ran his fingers along the seam where the wall met the floor. He found a crack, almost hairline thin, and pried up a loose chunk of stone, revealing a bundle of tools underneath. He extracted the tools and passed a long bronze pry bar to Icarus. He kept its twin for himself standing he enjoined his son to help him and together theypried up several of the heavy paving stones lining the Labyrinth’s floor. A depression lay underneath, within were two large objects wrapped in cloth. Daedalus and Icarus pulled the two bundles out of the cavity and tucked them under their arms. They moved a short way down the passage and stopped at a gap between two stones. Daedalus thrust his hand into the fissure and took hold of a hidden lever. As he pulled it, the stones slid apart. A cool night breeze blew into the opening.

Daedalus and Icarus stepped out of the Labyrinth and onto a narrow dirt track. The night was far gone. The moon played hide and seek behind scudding clouds and Orion hung low in the sky. With only starlight and moonlight to guide them, Daedalus and Icarus set off. They heard waves crashing against cliffs in the distance. They walked for an hour, with hardly a word spoken between them lest someone hear them and send word to the palace.

As they came to a spot on the cliffs overlooking the sea, Daedalus motioned for Icarus to help him clear away what initially appeared to be a large pile of brush. They laboured for another hour before Icarus glimpsed what lay beneath the camouflage. It was an enormous double catapult consisting of two sets of stone pillars standing side by side. The pillars bracketed a pair of wooden ramps pointing toward the sea at a slight incline. At the end of each ramp was a broad bow made of a large piece of beaten bronze. Just inside the arc of each bow and held in place with heavy braided ropes was a small wooden cart, barely big enough to lie down on. Drawstrings connected the carts to a system of pulleys which in turn connected each of them to a capstan.

Daedalus took one of the two long-handled shafts and handed it to Icarus. He took the other one and fitted it into one of the two square pegs in the capstan. “Come, Icarus,” he said, “let us be away from this place.”

Icarus paused. Standing the moon light, he gazed down in wonder at his father’s ingenious invention. “It looks so intricate father,” he said. “However did you think of it?”

Daedalus paused in the act of fitting the shaft into one of the capstan’s square pegs. “Hephaestus used Morpheus to send me a vision,” he replied. He turned back to his work, “hurry,” he said. “We don’t have time to dawdle.”

It didn’t take them long to pull back the drawstrings of the two catapults. Daedalus unwrapped his bundle and motioned for Icarus to do the same. Two sets of wings appeared on the ground as father and son removed the protective layers. Each set of wings was made of cloth with a covering of wax and feathers stretched over a thin wooden frame.

Daedalus helped Icarus strap the wings on to his back, deftly tying the knots so that Icarus’s wings would keep him aloft. “Do you remember what I told you, my son?” asked Daedalus.

Icarus nodded. “The wings are fragile,” he said. “We can not go too low or the feathers will get wet-.”

“-And if we go to high?” asked Daedalus.

“The wax will melt and the feathers will fall out,” replied Icarus.

Daedalus nodded. “Are you ready?”

Icarus gave his father a tremendous nod in return. They paused for a moment, praying several litanies, invoking the Litany of Hermes, for swiftness, Aeolus for favourable winds, Tyche, for good fortune and the Litany of Zeus for protection. When they were finished invoking the favours of the gods, Daedalus and Icarus laid down on the inside the wooden carts of their catapults. Icarus felt his heart beating very fast and took several deep, steadying breaths.

Beside him. Daedalus took hold of a long thin cord that ran back to a release pin. He steeled his nerves.

One.

Two.

Three.

Daedalus gave a sharp tug and the pins of each catapult came loose. The pent up tension suddenly released and Daedalus and Icarus were thrown violently forward into the air. Icarus’ heart was in his throat as the sea rushed up to meet him. For a brief instant that seemed to last several eternities, he thought that Daedalus’s plan had failed and that they were about to be dashed to pieces against the rocks. No sooner had Icarus thought this than he felt a hard jerk against his chest and his descent slowed. His arms were pushed upward and behind his back as the breath of Aeolus caught the underside of his wings. He beat against the air and the motion of his flapping arms allowed him to rise. He flapped harder this time, pulling his arms into his chest with stronger, broader strokes as if he could push the very ground away from him. and he rose higher into the air.

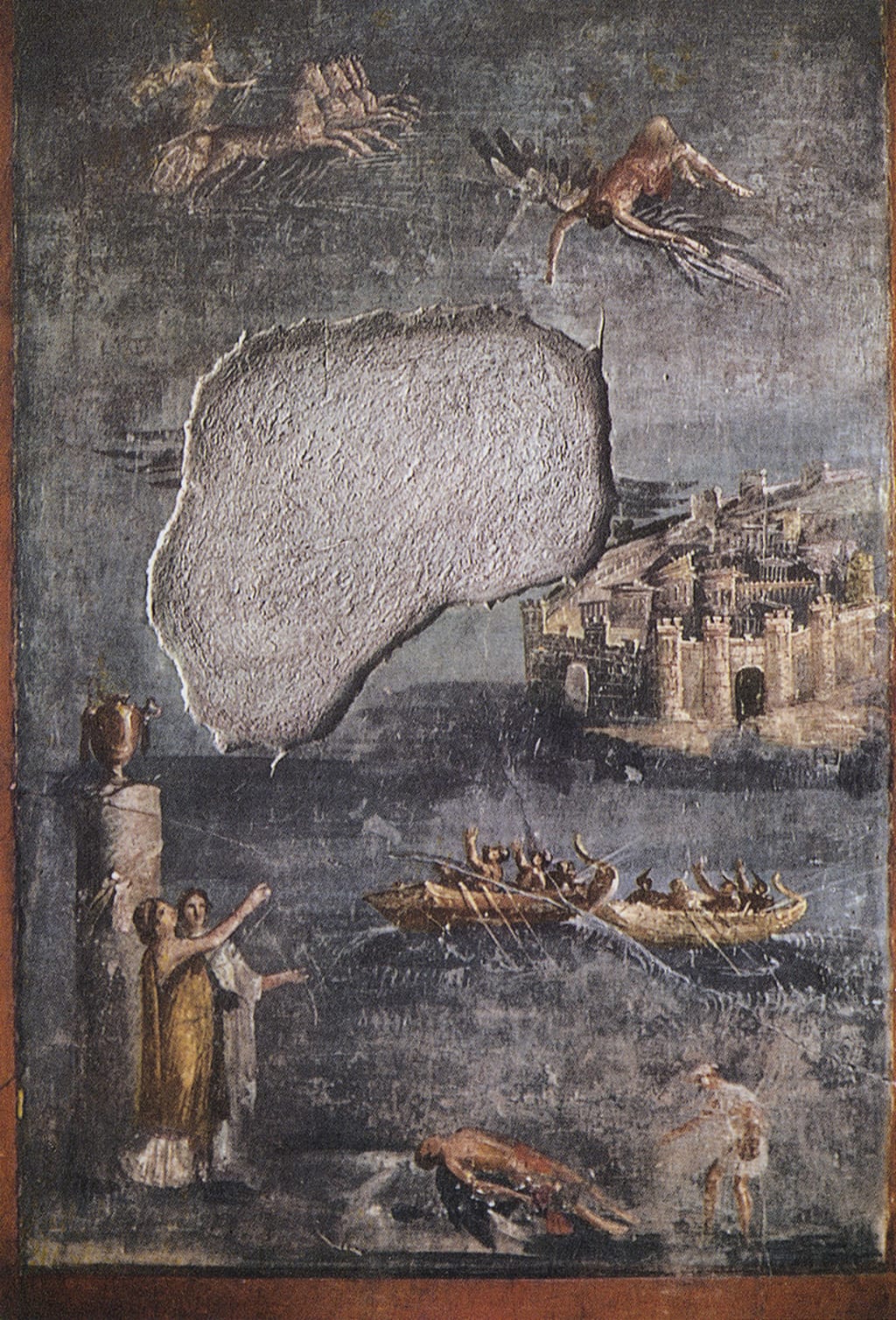

Icarus looked to his right. His father beat his wings in a smooth steady rhythm. As Icarus turned his head, his flight path shifted and he drifted closer to his father. For a heart-stopping second, Icarus thought they would collide and tumble into the sea, but Daedalus banked away, opening the distance between them again. Icarus sank slowly toward the ocean. It spread out beneath him in all directions like a wrinkled blue sheet. Icarus beat his wings against the air again, and felt himself rise higher. He tried to imitate the same smooth rhythm as his father. Out of the corner of his eye, the coast gradually fell away, until it was nothing more than a thin dark line, barely visible on the horizon. Below him, he could see the white furrow of a fat cargo ship as it plowed its way through the cobalt-blue waters of the Aegean. Farther toward the horizon, Icarus thought he spied the flash of oars. He looked closer and saw a sleek trireme streak across the waves, leaving barely a ripple in its wake.

This is wonderful, thought Icarus. This is what it must be like to be on Mount Olympus. He felt himself settle a little and flapped his arms again, rising another ten feet into the air under the influence of the additional thrust. Feeling the wind in his hair and tugging at his toga, Icarus revelled in the sensation of soaring like a bird. The sense of speeding along, suspended between the deep blue sea and the endless pale blue dome of the sky, made Icarus feel like Hermes, winging his way above the world, bearing the messages of the gods. Icarus felt himself flinch at these thoughts. It was not wise to equate one’s-self to the gods when in such a lofty position, and he quickly muttered the Litany of Hermes.

Out of the corner of his eye, Icarus saw his father bank suddenly, turning away to the west and he followed suit. Far off on the distant horizon, the long fingers of the Peloponnesus jutted out into the Aegean Sea, sliding away into the distance behind him. Icarus levelled out his flight and surveyed everything below him. He spied the white plumes of a pod of bottlenose dolphins frolicking amid the waves. Icarus flapped his wings again, putting on a burst of speed and gaining altitude in the process. The coast of Africa appeared beneath him as a dark, dusty brown smudge. The frolicking dolphins disappeared and Icarus could see his father soaring below him. The white feathers of his wings stood out sharply against the cobalt Mediterranean.

Icarus rose higher and higher. The world spread beneath him, like one of the many scrolls in his father’s study. He lost sight of individual cities and towns. He could barely make out the largest of buildings, betrayed by a glint of marble and the bright red tiles of their roofs. He felt the sun on the back of his neck and basked in the warmth. He flew, savouring the view, the wind and the warm sun on his face.

As the heel of Magna Graecia began to emerge over the horizon when it happened. Icarus suddenly felt something hot and sticky dribble on to the back of his neck. For a second he wondered if it was perhaps a bird, but that’s absurd-thought Icarus dismissively-birds don’t fly this high. Out of the corner of his eye he saw something fall. It was white and viscous looking and had a tuft of feathers clinging to it. It was followed immediately by a trail of waxen feathers, and another, and another. He did not understand at first. Then a sinking sensation settled low in his stomach. He realized that he had dropped slightly. He flapped his arms and rose a little, but sank again, the moment he stopped flapping his powerful wings. Icarus flapped his arms, pulling against tired and unyielding muscles and then rapidly sank twenty feet.

He spread his arms as wide as he could, in an attempt to slow his descent. He felt himself slow a little, but continued to fall. As he sank, Icarus heard a whistling noise, like air being forced through a small hole. He twisted his his neck around and craned his head back to see where the noise was coming from. As he did, he was pulled into a wide, sudden turn. Icarus saw a bright shaft of sunlight pierce through a hole the size of a drachma in the wing above his left shoulder. As Icarus watched, the hole in his wing grew steadily larger and he felt himself falling at an ever-increasing rate of speed. A hazy shadow fell across his face. Something made his eyes burn. Smoke-he thought-something is smoking. Then he saw flames licking the feathers around the hole in his wing. The hole continued to get bigger. For a brief second, Icarus tore his eyes away to stare down at the water. It was a mistake. The surface of the Mediterranean, which not long before had seemed to be as placid as a lake, suddenly appeared to be a pair of all encompassing arms reaching out to grab him.

Icarus flapped his arms wildly, but all he managed to do was fan the flames. He felt a searing pain on his back and jerked suddenly as if someone had struck him with a hot needle. His toga had caught fire. Without thinking, Icarus reached around behind and tried patting out the flames. Had he not done this it is entirely possible that he would have made it to Sicily, but it was not to be. Icarus felt the moment his wing tip began to burn. At that exact moment, his rate of descent increased markedly. The wind whistled in his ears. His eardrums popped. He tried to throw his arm back out, but to no avail. The wax in his wing had melted and fused his arm in place. He tumbled through the air. The world spun, as he dropped, head over heels.

Sky.

Sea.

Sky.

Sea.

Sky.

Sea.

Icarus thrashed helplessly grabbing at the air while trying to free himself. He drew in a gasping breath and coughed, taking in a lungful of smoke. His eyes watered from the soot and he could barely see. A mercy for Icarus that he was unable to see the appalled look on Daedalus’ face as his son plummeted past him, helplessly spinning and on fire, plunging and hissing into the sea.

About the Creator

Terry Long

I am a perpetually emerging writer on the neurodiversity spectrum with a life long interest in the space program. I live north of Toronto, with my dog Lily. I collect and build Lego kits as a hobby.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.