The Burning of Los Angeles

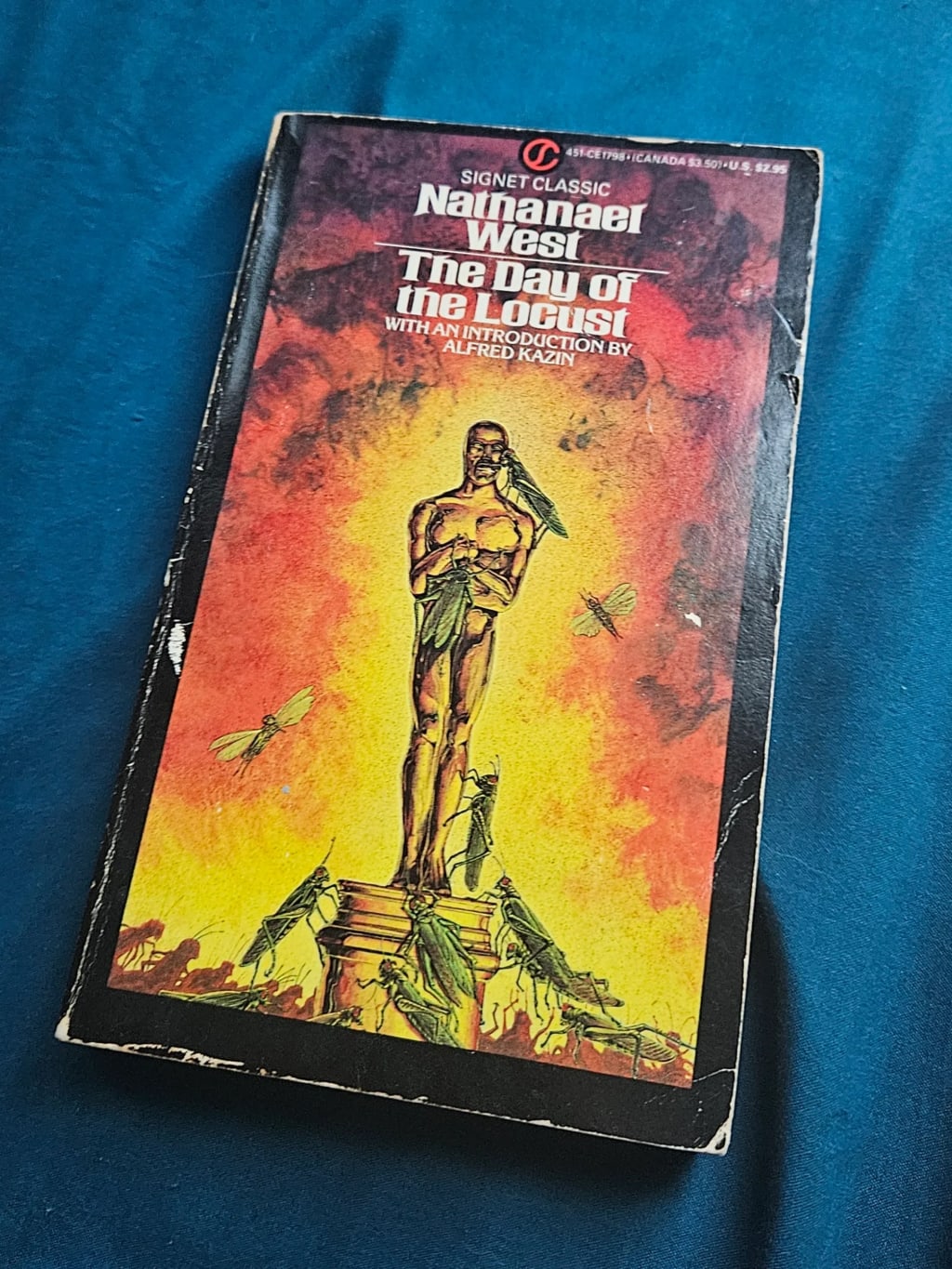

Nathanael West's "The Day of the Locust"

Prior to films like Babylon and other works of fiction that asked the starry-eyed youths to be hesitant on their Hollywood dreams, the American public got their first warning cry in the form of a tightly-wound novel by the satirist Nathanael West. The Day of the Locust, rife with meandering lovelorn suckers, drinking and pretending to paint and act whilst going mad under a Californian sun, presents a Los Angeles that seems to resent and scoff at the novel’s characters; as if they should’ve known, the rallying cry of following your dreams presented in the “pictures” as they were called wasn’t meant for them.

Tod Hackett, in some perspectives, isn’t a likely protagonist for that of a showbiz “American Dream” type story. He shows little to no interest in film (“pictures” as they’re called at this time) but is instead a painter, Yale-trained at that, having been recruited to work on designs for sets and posters. While his work is stable and consistent unlike that of his peers and would-be femme fatale, he proves to readers very quickly that he is very much a bottom-feeder, pathetic as those around him. His self-awareness and compassion at times spares him from contempt in our eyes but his willingness to endure and place himself in these environments keeps him in the bottom of the barrel.

For in his neighbor, Faye Greener, he finds a love interest as mean-spirited as she is untalented as an actress, living with a doting elderly father (who is, for a good time, Tod’s only real friend). Faye is going to be famous any day now, but until then, she exclusively (and openly) is interested in men who can either provide her with wealth or are at least good-looking, neither which apply to Tod.

The novel, just barely 200 pages scratches a few subcultural surfaces of Old Hollywood, ever-vain and relentlessly cynical, showing a different light than what’s shown in success stories or romantic comedies and musicals. Plot-wise it’s purposefully uneventful, Tod lurking with Faye and her many “friends” and suitors (one of whom shares the namesake of The Simpons’ patriarch). As previously stated, we find Tod, despite circling the drain to insanity and hopelessness with the rest of them, dealing with moral quandary with these romantic competitors, writing some of them off but going as far as to befriend others, despite seeming to never stop carrying the torch for her. But a small fantasy he has toward the novel’s climax, despite its detachment from what actually happens, will cause many to desert any prior emotional investment, which I can only expect Nathanael West wanted from this scene.

And the ending, more concerned with submerging its readers into a nihilistic tailspin than tying up any possible notion of hope, cares less about making Tod a hero and more about making a cautionary tale out of pipe dreams and mob mentality. The themes and toxic environments are not things that have improved since 1939 when this novel was published. West wrote a few short books before dying tragically with his wife in a motor accident in 1939. He was 37. I can’t help but wonder what kinds of dark commentary and satire he would have been writing had he survived until the end of the century. If Mulholland Drive serves as the ultimate antidote to the Hollywood daydream, The Day of the Locust is the initial warning.

About the Creator

J.C. Traverse

Nah, I'm good.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.