The Bible Erata

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver is "The Good Book" For A Writer in Search of Purpose

Art by definition is subjective. The art of writing, and the appreciation of it, not only subjective but visceral in emotional resonance. The unique, extraordinary and sometime revelatory craft of penning words and turning phrases, to ethereal elucidation of the human condition, elevates the art and leisure to a higher purpose and pleasure. I think of those books I have revisited and the author's method's and purpose. Whether with raised fists against conventional form of the novel, such as Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridien with its dearth of punctuation and lack of convention or in epic scope and breadth for a modern tome such Steven King's The Stand, both call to me at regular intervals. Sometimes, I reread the simple, slow and slyly building boil to literal explosive climax of John Irving's "A Prayer For Owen Meany" or Richard Russo's Empire Falls, but every great novel is a chance to learn something of the craft of writing and the the human experience in a simple setting.

My mind has always need the use of words and language to communicate and empathize. My heart has always needed thoughts and words to tell stories. My soul has always needed to write. But writing about the great unknown that is life, while a gift, and endless and finite journey of living and in the near infinite stories of life. For me, the tradition of storytelling began with religion which played a constant refrain well into early adulthood. Countless hours spent in the theater, telling stories on stage continued and added to my journey as a storyteller. As an adolescent, I would write plays and short stories to past the time. The value of hearing the same stories told over, again and again, became a lesson in interpretation and expression. The plays to me seemed so malleable to me as to be something that was different with each reading, rehearsal or performance. But, reading stories was just as wonderful to me and my mind would often wander down paths in journeys never meant by the particular writer I was reading. I read many of the classics of literature and theater, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Salinger, Cummings, CS Lewis, Huxley, Brecht, Chekov, Durrenmatt, Ibsen, Pinter and most of Shakespeare, were the basis of my education. Books evolved to become more of a path for academic achievement and not for pleasure well into college. With the exception of Steven King, which I hid, there was little reading I did for pure enjoyment. That changed when I graduated and had more time on my hands on the West Coast, which seemed to be decidedly more C-Average than the Ivy-covered halls of the academic institutions that had guided my reading choices. Just shy of a year out of college, I discovered a book that changed me, and made me want to be a writer with purpose. I read The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver and I knew that if I had to chose one way to contribute to this world it would be through words and, dare I hope, that those words could an addition to the canon of American literature through the novel.

My appreciation of the story itself and how it unveils itself. The crowning achievement for me in all the written words is unlikely Poisonwood Bible is prima facie a story of a missionary and his family doing "the Lord's work" in colonial Africa, specifically the Congo. The Southern Gothic infused context of Southern Baptists, Southern gentility, and Southern "dispositions are familiar to me as a native son of the South and from a religious upbringing and adherence to those traditions. Southern Gothic is used in the novel as a precursor to travel to the "Dark Continent".

The turning of the tables of social structure open my eyes to the simple fact that it could be done. The knowledge has affected my life and changed me as an interpretive and creative artist, a writer and a human being. A medicine and meal to me on a personal level, as an African American not far removed from the world in which the central characters begin the journey. Southerners, with strong religious It was incredibly cathartic to see African characters across a spectrum of social and economic situations, with such awareness of power structure on so many literal higher levels, that the racial dichotomy for the characters is a graceful rebuke at best, and the quiet part is what it doesn't say at all about US race relations, which silently speaks volumes in the Poisonwood Bible.

“With no men around, everyone was surprisingly lighthearted.” The Poisonwood Bible

My own lamentable knowledge of women's literature or feminist writing on first reading this book has altered not just what I read, but how and why I write. So much of my reading has have been about European men from, hero or anti. This story challenges the convention and the lives of the women who tell the stories have many layers and tiers. Identifying with one or more marginalized groups means that I have learned to adjust my thinking and even world view to seek to empathize rather than disregard. To seek out and listen to critical feminists theory is to me a natural progression that The Poisonwood Bible does with clarity and conviction.

A mother, Orleanna and her four daughters, Rachel, Leah, Ada, and Ruthie May comprise the five narrators of the story. Their voices are so distinct and the characterization of each is a chance to view the story and the events from an exponential level of emotional, social, theological concepts framed with overwhelming political statements on colonialism and race. It's a rare writer that can juggle the voices at the right times to propel the story so deftly as the author Barbara Kingsolver does here. You feel the lost and mourn deeply for the remainder of the characters lives. As a writer I want to learn the use of words and skill of language that is able to entice me into a world and make sure I long to stay there even if it hurts. As a writer one of the most effective uses of language became handily apparent not in use of grammar or language but in character and their development and use as a narrative voice. The accomplishment of presenting more than one, as an oft interloper on the stage, has always enticed me. As Kingsolver reveals not one but five and more narrators and each one becomes reliable or not according to interpretation and situation I took as a feat worthy of praise but even more so of study. The female gaze, and voice, and lack thereof in the Bible Erata is a a testament to the author's resolve and academic expertise on the rights and roles of women. Their voices being heard so clearly, just not to the characters in a story with moments that are simply tragic. One riveting an awe inspiring ccharacter as narrator is the hemiplagic and mute, Adah, who ironically in this story does not speak to any other characters and her pronounced infirmity and precocious and ingenious mind add to the irony situationally and theoretically and illuminate the woeful reality of the rights of individuals with disabilities. These rights and liberties are rarely considered compared with the numbers of people whom actually exist with disabilities in environments that micro-aggressively hostile. Adah is one of my favorite characters of fiction. In her thoughts, often relating to palindrome, the story and her judgement are unveiled. One of the ways Kingsolver not only shows a mastery of situations and characterization but a mastery of the possibilities of the English language, its nuances and efficiencies of communication much larger in subjects than their literal meaning or use. This is art reimagining the possibilities of storytelling.

Reading for myself and many others has always been literally and a matter of black and white. African American literature and then the hegemonic canon were two different entities and exercises. When I read about African American characters or purely African descended characters with whom I most identified racially it was almost always through the lens of slavery or Jim Crow and colonialism. Certain tropes were ingrained as mush as to be visceral, i.e. The noble or defiant or mystical negro in bonds of enslavement with eyes heavenward or at least north toward freedom, the Great White Savior in the jungles of Africa, or Non-Playable Characters in a journey into a Heart of Darkness. Kingsolver did for me what few authors had deemed necessary, the Non-playable negroes had voices and knowledge and agency that resonated. Some are good and some are bad. Some are wise and some less than. Even those who are African descended who claim to channel an unearthly power in the Poisonwood Bible, were less mystical, than charlatans fulfilling a role that was somehow more true than the Remus', Rufus' or Reds' long peppering the modern canon of American literature.

“The death of something living is the price of our survival, and we pay it again and again. We have no choice. It is the one solemn promise every life on earth is born and bound to keep.”

The Poisonwood Bible -Adah Price

According to Masterclass, "You kill your darlings when you decide to get rid of an unnecessary storyline, character, or sentences in a piece of creative writing—elements you may have worked hard to create but that must be removed for the sake of your overall story. " Barbara Kingsolver not only kills her darling, but she killed mine too. It was one of the few times I have openly wept at the death of a character and the portrayal thereof. I won't spoil it for you who have not read it, I am not the writer that Kingsolver is and could not even if I tried. I can never hear the words, "Mother, May I" again without tears welling and that is a powerful testament to the craft of a writer to reimagine how emotions could be elicited and manipulated with words that I have heard a thousand times, crafted into the story in a setting so bereft of any comfort from voices that should and would sing like angels. The scene of note in the Poisonwood Bible would melt any heart made of supple flesh and warm blood. The possibility that such emotion can be elicited with words and setting and character has become what I strive to do.

At the time Poisonwood was released the notorious book critic for the New York Times declared the "social allegories" to be "heavy handed." Written in a country that, even in 2023 or in the 50's and 60's in which the novel is set, refuses to accept or acknowledge its clear, recent and ongoing sins - of slavery, Jim Crow, or micro and macro aggressions, Stop and Frisk, and Stand Your Ground- the critique of heavy-handed is a rather obtuse and onerously reeks of entitlement and privilege. Kingsolver's willingness to suffer the slings and arrows of the likes of Kakutani says more of her strong resolve as a spectacular craftsmen of social commentary that Kakutani's insistent insouciance belittles. Were more writers committed to purpose and assertive in their social statement, perhaps we would need less strength of handling for such a heavy burden.

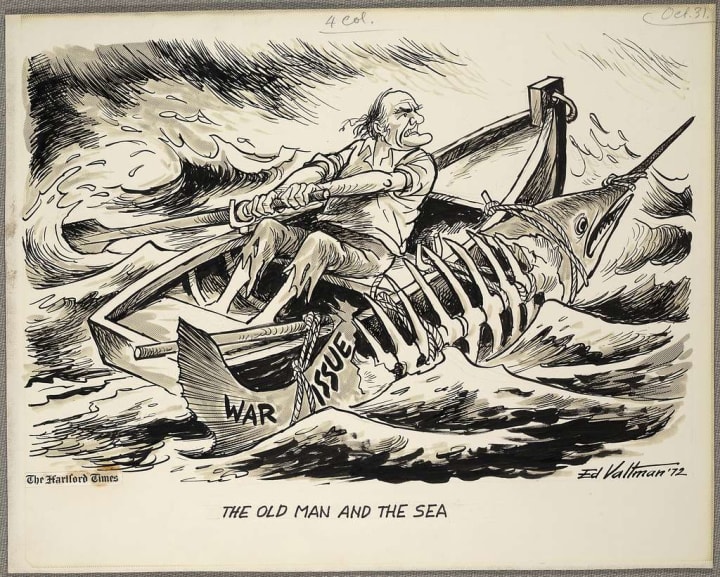

To think that in my repeated readings of the story I have never once thought of Nathan Price, the great ministerial presence of a father, was never the main character, but one inflicted upon his family, the village he aims to conquer, and the continent he seeks to tame, shepherd and cultivate. The hubris of man is too well known to elicit any sympathies. Willful assertion of ones' own certitude in all situations, and yet not understand that consulting "the good book" for farming in the Congo, doesn't reap quite the crop you require. Or in the author's own words, “Don’t try to make life a mathematics problem with yourself in the center and everything coming out equal." But these are the least of Nathan Price's worries.

“My father says a girl who fails to marry is veering from God’s plan - that’s what he’s got against college.” The Poisonwood Bible -Leah Price

The political leanings that are apart of the story are undeniable but less important to me than any other story that I had read to date with the exception of Achua Achebe We Regret To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Family of Angelas Ashes. Presented through a feminists spectre allows the medicine that is the real politik in the remnants of Greco Roman and Northern European ascendancy and the hegemonic world view. The rights of women wo prove strongest yet with the least amount of power in world and life changing events. The US Role in post colonial imperialism is not ignored, but the reader is as gob-smacked by the situation as the characters that are in situ. Th events in the region that the book illuminates begged for further reading; King Leopold's Ghosts by Arthur Hochschild was where I turned.

Darkness in the world is a constant, but we must keep moving forward. Art is a way to endure and the voices of women must and will be heard whether time or opportunity will be the quicker in the marathon towards the ribbon of equity and exclusivity remains to be seen. Until publishing and media reach parity, our canon and even history are the poorer for it, now the hyper-kinectic visual storytelling of the technological revolution is what constitutes storytelling from an anthropological level, so gratitude is in order for Barbara Kingsolver, an author who is master storyteller. The Author is capable of listening to and speaking on behalf of so many in one imaginative, rich and dynamic parable, that really echoes for me in a novel, sometimes in life and always in writing.

The lessons I learned in the story have proven biblical and in need of revisit when found in situations that bare similarities to any folly in uncertain places with very uncertain outcomes. When I have been in situations within the third world, and emergency situations, it was the comfort of Kingsolver's Bible, in the characters and setting as unimaginable to them and the reader, that gave me comfort. This was especially true when I worked with NGOs and Missionaries ,who seldom knew what was best for the native people. Listening to the people around me was the mantra I took from The Poisonwood Bible; How to wash fresh produce? Where to roam after dark? How to catch a bus and travel across the country. One takes for granted in the First World the sheer number and myriad ways to die in The Third World. Know where you are and accept that first. The Poisonwood Bible taught me that lesson and changed how I cope as a human being and what I aspire to do as a writer.

About the Creator

Herman Wilkins

It all starts with a good story, who's telling it, how, when and why, then all that's left is what it takes to get it heard. Any way you hear a story, in print, Blender or 65mm, it starts with words. Any writing you keep reading is art.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.