William May: A Voice Forged in Greenwich Village

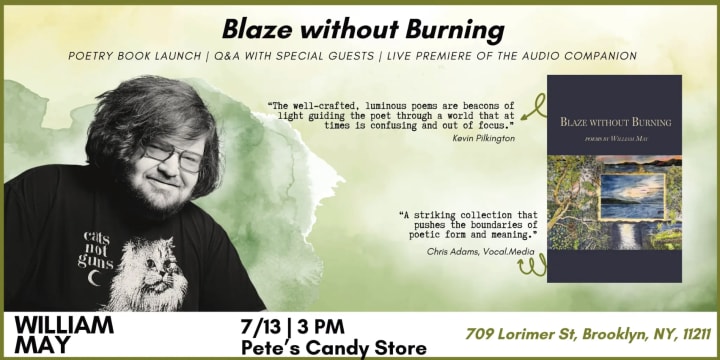

Exploring Identity, Creativity, and Neurodiversity in His New Collection Blaze Without Burning — Live Reading & Q&A at Pete’s Candy Store on July 13

William May writes with the soul of someone who has lived many lives in one city. A fourth-generation New Yorker born and raised in Greenwich Village, May's work carries the grit, humor, and heart of a changing city filtered through a voice that is entirely his own. His latest collection, Blaze Without Burning (Finishing Line Press), is a poignant meditation on memory, vulnerability, and the often overlooked details that make us human. Diagnosed with a learning disability early in life, May never followed a conventional path, but instead carved out a unique creative language that is lyrical, observant, and unflinchingly honest.

His perspective, shaped by a lifelong commitment to storytelling on his own terms, is both intimate and universal. On Saturday, July 13 at 3PM, William will be giving a special reading and participating in a live Q&A at Pete’s Candy Store in Brooklyn, one of New York’s most beloved spaces for emerging voices.

Whether you're a longtime fan or discovering his work for the first time, this is a rare opportunity to hear from a writer whose journey is as compelling as the words he puts on the page.

Vocal Media Interview William May 6.9.25

Your chapbook employs a unique “twin poem” structure—what inspired you to pair poems in this mirrored way, and how did the idea evolve during the writing process?

The structure for Blaze without Burning developed rather organically as the book was developing. As a writer, my process tends to be primarily generative, and I will usually write quite a lot and put the work aside to revise later, often as part of curating the work and preparing it for submission. Blaze… came together while I was working with my friend, the poet Freesia McKee. At the time, she was living not too far from me in Florida, and she was assisting me to revise some of my poetry. At one point, she had pulled together a group of poems (the poems that ultimately became this collection) with the suggestion that they would make a good chapbook. It was while revising the poems and organizing the collection that the connections began to appear, and, at some point, I just started pairing up the poems. Obviously, there was more work to it than that. I had to shape the poems to bring the pairs together in a substantive way, which was challenging, but I think it helped to provide me a bit of guidance in the process of revising the poems for the collection, for which I am quite grateful.

The title Blaze Without Burning suggests transformation without destruction. What does that phrase mean to you personally, and how does it echo throughout the collection?

I am a bit hesitant to be too exact about the meaning of images. One of the important aspects of symbolism and metaphor, at least for me, is in the space it leaves for the audience to enter and engage with the work. If I wanted to be more exact, I can use more specific and literal terms, while a symbol allows each reader to bring their own personal resonances to the work. I do think that, for me, at its center, it’s an image about a certain type of duality, and about the danger of being on that edge, that space harnessing the power of the conflagration or being consumed by its flames.

Can you talk about how your experience as a Neurodiverse writer shaped the themes or forms in this chapbook?

As a person who is neurodiverse, I came to recognize that my experience of the world is often not in line with what others are experiencing. This is both obvious, but also very difficult to actually understand in a real intuitive way, since we each live within our own subjectivity, and can’t really compare it with anyone else’s. In some ways, that is actually freeing for me, as a writer, because I can’t help but communicate things that reflect my experience of the world. Beyond this, and particularly because I am dyslexic and my own neurodiversity has so much to do with language itself, I think that I have realized, as my writing has matured, that I often think about words and sentences and the various linguistic objects in a much more deliberate and conscious way. For me, the experience of reading andwriting are both things that still require a certain degree of conscious effort in a way that is not true for most proficient readers. Now, don’t get me wrong, it is not as if that is a difficulty or problem, but it is an aspect of my experience, and I believe it makes me aware of things about how language operates in ways that other writers might not perceive. I know, for example, when I do things with words to change the order of information in a sentence, I am calibrating just what the impact of that is on how a reader will process the information while engaged with the text. That is something that I considered as a basic part of how I think when writing. In that way, I can’t imagine the kind of poet I would be if I weren’t dyslexic, and I have to admit that much of my love for language is a direct response to the effort and dedication it took for me to achieve literacy as a child. Those impacts are so fundamental and pervasive that I can’t point out any one specific aspect of Blaze without Burning as a direct reflection of my neurodiversity.

You’ve described reading and writing as sacred—how do you maintain that sense of reverence in your creative routine today?

Language is a very deep part of the human experience. If one begins to research the role language plays, not just in communication but in cognition itself, one begins to understand the idea that the world is, in certain ways, defined and created through language. We don’t just experience the objects around us, but we experience them through the words that have been applied. I could take the same piece of furniture and tell one person it is a stool and another it is an end table, and each of them would treat that object as something different, and probably be surprised if the other one showed up and acted as if it was another thing entirely. Writing isn’t simply the act of crafting a specific communication, but it is also a way of creating real experiences for a reader, and even cultivating new ways of thinking about the world. That is the power, for example, of a good metaphor. If I described a tree without its leaves as a toy soldier abandoned on a snowy field by some careless child, that is very different than speaking of how the branches against the sky spread out like blood vessels: each one is going to evoke something different and make you consider a tree in a way you might not have before. For me, it is a lot about the ways that language can be used to include and exclude. For example, I very often stray from using a specific sense when I can describe something vividly without calling on something like sight or sound, as I am aware that those can be experiences that are exclusionary for certain readers with disabilities. I tend to think of poems as actual physical objects, not just a bunch of words strung together, and I think of building that object as a kind of ritual practice. It is something I carry with me when I sit down to work, and I think it is also part of what compels me to return each day, even when I might feel a bit discouraged or distracted by life. I began my answer here, by speaking about how language creates the world that we experience, and I mean that both as a metaphor, but also as something that is quite literal, and I think that bringing that into my work forces me to recognize that what I am doing is something much closer to a magical or spiritual act than is often considered, and I have to take that seriously.

The artwork by Richard Frank on the cover is evocative—what drew you to that particular painting, and how do you see it conversing with your poems?

It took a bit of time to find the artwork for Blaze without Burning’s cover, but it was one of those situations where the moment the right answer appeared, it was obvious immediately. I think that a large part of what I found evocative in the image was Frank’s use of duality, and the sort of intertextuality of a painting within a painting. Blaze… is very much a work that has layers and interconnections between the poems, and, although it is not one for one, I felt those elements were something shared by both pieces. I also have to acknowledge that I was drawn to the work because Richard Frank was a Florida artist, and I connect with the imagery in that way as well. That little owl, for example. on the side of the painting always reminds me of the one I encountered one evening, perched on the mailbox outside my home in Boca.

What role does resilience play not just in the content of your poetry, but in your journey to publication itself?

Anyone who wants to be an artist has to face rejection. This has always been true, and it is hard to imagine that it has ever been as true as it is today. I don’t think this is a bad thing, to be honest: it is a sign of the fact that more people are attempting to speak and share their experiences and creative expression, which is probably a very good thing for society. Still, as an individual creator, it can be daunting to deal with rejection after rejection, even, or perhaps especially, when you have real faith in the work you are sending out. I don’t know that there is a lot to say about that which can make it more palatable, and the truth is, rejection can be upsetting, even disheartening. I don’t know that I am particularly good at dealing with this reality, and I can admit that receiving a rejection can often darken an otherwise pleasant day for me. If I have done anything specific as a writer, anything that I might recommend as a strategy, it is only that I have kept going. I don’t know that anyone has a real formula for getting things right in this arena, but whatever else, it’s obvious that nothing will happen if you aren’t staying in it. For me, the best tool I know for dealing with that is often in writing itself. As I said, I tend to write a lot, and I tend to write every day. For me, that has become a kind of ritual, and when I get a rejection, the act of keeping that ritual is a reminder that I am still going, that I am in it. Also, I do enjoy a bit of fun, at times, writing poems that are, in some way or another, responses to being rejected. Most often, such poems are not particularly good, but it is helpful for me to be able to turn those negative experiences into prompts for writing, if only as a way to help facilitate getting a poem started when I am still caught up with the ego slam of my work not being accepted.

In your podcast episode about the presale, you explored the publishing process—what has been the most surprising part of launching this debut chapbook?

In terms of getting the book itself ready, I think, if I am honest, the most surprising thing is just how smooth it really has been, ultimately. There were certainly times when I, like anyone expecting for the first time, was nervous that things were about to slide off the rails, but it always turned out to be just my own fears and nothing real. I also have a great team I have hired supporting me, who are very adept at diffusing many of these anxieties for me, and Finishing Line Press, my current publisher, in spite of a fairly small team, have a very practiced way of handling things which made it, for the most part, pretty easy. In larger terms, in the sense of my own experience with putting the book out there, I think that it has been very rewarding, even at this point, to find that there are people who are eager for the book, and I should admit that I am buoyed by the interest that Blaze without Burning has already garnered. Of course, I am also aware that this is still early.

As someone who started writing poetry at age 9, how has your voice matured or shifted over time, and how is that reflected in Blaze Without Burning?

I often talk about my approach to writing as a practice. In part, this is because I recognize the fact that the only way to gain skill at any endeavor is through repetition: each time I sit down to write another poem, I am practicing that skill in a way that will help to develop it for use in the future. That is to say, each poem I write is an opportunity to learn something new about the process of crafting poetry. I write a great deal, and my poetry will often go through cycles. There are times when I am writing many narrative, often surrealist, poems, and others when my bent turns towards confessional writing; at other times I may have a run of poems about the lizards and ducks endemic to my Florida neighborhood. When I was younger, my poetic scope was far narrower, with much of my early work stuck in a narrative framework that often strayed from personal revelation. I think that focus was a necessary part of limiting the variables in order to learn certain core elements of my craft, in much the way that a carpenter may begin by making a whole bunch of the same chair, until they have the proficiency to feel comfortable embellishing with their own design. Now that I have developed a certain familiarity and skill with my tool kit, I am less restricted in terms of what I think I might be able to create. The thing that is most interesting, for me, though, when I go back and read poems from earlier in my life, is just how much I recognize in the work. This is the grand mystery of voice, of course, a subject that I imagine has, inexhaustively, taken up a great many volumes. Once a voice begins to make its presence known, it will always be there, even when one attempts to do something entirely unlike what has come before, which is both a blessing and a curse. I can’t help but experience Blaze without Burning as a moment in time; my writing is always in process, moving towards some new expression, but it is always connected and flowing from that same source, filled with the same waters, as it were. This collection contains work that reflects a certain period in my life, not as a static moment but as steps in a larger set of journeys.

How do you hope readers engage with the “twinned” nature of these poems—do you want them to read them in pairs, or discover the connections organically?

I tend to think of Blaze without Burning as a kind of journey, with a movement inwards to the center, and then a trip back out again, and I do like the idea of the reader discovering that as part of the experience of reading the book. One of the elements that was really important to me, and this might sound a bit silly, was making certain that the table of contents was designed in a way that only displayed each title once, specifically so that readers might discover the twin structure while traveling through the book. I do think it also provides opportunities for considering the work in other ways, especially if I am lucky enough to have enchanted readers into returning to the book again, after their first trip through. What is most significant about it, for me, is that it unlocked my ability to craft something whole out of the individual poems, and I think that is something that can be experienced through the work, whatever path is chosen.

What advice would you give to other emerging writers—especially those who identify as Neurodiverse—who are navigating their own paths in poetry?

There are two kinds of advice that I can attempt to offer. In terms of building a career, and I must acknowledge that I am not the great expert in this arena, I think I’ve already provided the most significant advice, which is to continue in spite of the obstacles. Rejection is not fun, and it can be particularly challenging for some who are neurodiverse. It is important to find ways of acknowledging and releasing that frustration. I found it very significant to accept that my frustration and upset was a valid response, and, as I said earlier, I often have found ways of venting some of that through writing (mostly bad) poems. As well, I think it is important to have others to support you on your journey in some form. This can be a community, a workshop or peer group, it can be one or two individuals you are just friends with who share a creative passion, but having support is very significant. As a person who is dyslexic, I found that the process of actually managing submissions is not something I am really adept at, indeed, the idea of it feels overwhelming from the start, and I realized that I needed to have help for that, so I have hired people to provide assistance in that area. That was a big part of how Freesia McKee and I first began working together, and I know that Blaze without Burning would not exist without her. It is important, obviously, for any writer to recognize their skills and what they might need assistance with, but I think it can be particularly so for the neurodiverse, at least it was for me. Beyond this, community can bring much more, can open up possibilities that you might not have considered, for example, I am lucky to be in a community with some amazing musicians and who just released a soundtrack audio companion to Blaze without Burning, something I wouldn’t have even considered on my own, but the composers Denise Marsa and Paul A. Harvey, wrote an amazing collection that responds to and converses with the entire book in a way that feels really special (more about the album can be found here).

In terms of developing as a poet, the best advice, unsurprisingly, is to read and to write. I spent a long time when I was younger believing that inspiration was something that came and went, but when I decided to actually discipline myself to write each day, I discovered that the truth is more like inspiration is a stray cat, and if you start to feed it, it will keep coming back to you. Even just writing poems about how you don’t know what to write counts, and it will probably not be long before you realize that it was just a starting point and there is something more to be discovered as you keep going.

Find more of William May here:

https://williammaywrites.wordpress.com/

Catch a very special Q&A and read at Pete's Candy Store

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.