The song, “Hit Me Baby” by Britney Spears marked the encouragement of stereotypically sexualized personas among young girls and women. Apuke, Jigem, and Lingbuin (2019), stated that research has shown a significant rise and development of music videos due to its enormous appeal to express a variety of emotions, ideas, and feelings. Meanwhile, there is an increasing concern about the negative impact of music on the perception of women in society including its misogynistic connotation of women. Sexuality in music videos has become more intense and more frequent and women face a constant reminder of images informing them who they should be, what they need to resemble, and how they are expected to act.

According to the objectification theory developed by Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts (1997), sexual objectification is the experience of being treated as a body (or collection of body parts) valued predominantly for its use to (or consumption by) others. Experiencing sexual objectification causes individuals, especially women, to treat themselves as objects to be displayed, a tendency known as self-objectification. The theory presupposes that self-objectification can have deleterious destructive effects such as body shame, anxiety, reduced flow experiences, and lower internal body awareness. As a result, these effects can lead to long term mental and physical health problems such as eating disorders, depression, and sexual dysfunction.

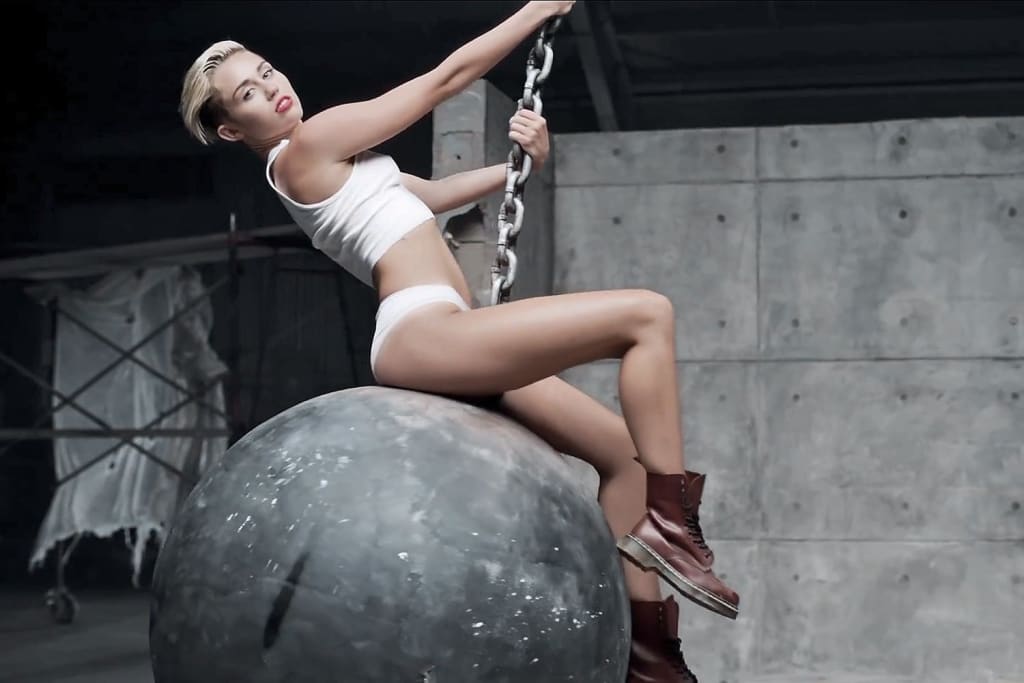

Another negative effect of experiencing self-objectification is the decrease in cognitive performance. In several studies, Quinn, Kallen, Twenge and Fredrickson (2006), have found that induced self-objectification lowered the ability to carry out cognitive tasks. An interesting question then is, what environmental stimuli activate self-objectification? A majority of research pointed to the media as an important environmental context for self-objectification and the type of popular media that provides examples of sexual objectification of women’s bodies in music videos. Content-analytic work has documented that sexual exploitation, objectification, and degradation of women are commonplace in music videos (Frisby, and Aubrey, 2012). Through the use of provocative clothing showing excessive skin exposure, sexual dance, and the surveillance of women’s bodies, women are begin portrayed as sex objects.

Two recent studies have explored the impact of sexual objectification in music videos on male college students. The first study by Kistler and Lee (2010) discovered that male college undergraduates who viewed highly sexual hip-hop music videos demonstrated greater objectification of women, sexual permissiveness, and stereotypical gender attitudes than the other male participants who viewed less sexual hip-hop videos. The second study by Aubrey, Hopper, and Mbure (2011) selected a stimulating framework to assess the effects of sexually objectifying music videos on male college student’s sexual beliefs. The results revealed that men who viewed the videos high in sexual objectification reported more adversarial sexual beliefs. For example, the beliefs that women are sexually manipulative, more acceptance of using violence against women in sexual relationships, and less concern for the sexual harassment of women.

The research conducted by Karsay, Matthes, Platzer, and Plinke (2018), was to investigate the effects of the exposure to sexually objectifying music videos on viewers’ subsequent gazing behavior, called media priming theory.The media priming theory as explained by Roskos–Ewoldsen, Ewoldsen, and Carpentier (2009) is that exposure to media content can temporarily stimulate certain concepts in line with the content (e.g., objectification of women). This translates to the objectifying gaze, which Karsay, Matthes, Platzer, and Plinke (2018) defined as the exposure to sexually objectifying music videos that might prompt an objectifying gaze pattern used when viewing pictures of women.

When individuals view women, these concepts are automatically sparked in the minds of the viewers. As a result, it seems logical that the activated concepts prompt the processing of information, which in terms of priming, means that “viewers are more likely to process visual information (i.e., body characteristics) congruent with the objectifying video” (Janiszewski, and Wyer, 2014) and hence apply an objectifying gaze to the pictures of women. Supposedly, this process is unconscious, individuals are unaware that objectifying media can affect their gaze patterns.

Rasmussen and Densley (2017), explored the portrayal of women in country music to determine how they portray female gender roles, the prevalence of their portrayal of women as objectified, and how those portrayals have changed over time (1990–2014). They highlighted that country music may be prone to objectifying women because it is mostly male-dominated. Also, lyrics in songs sung by the male singers differed from those in songs sung by the female singers.The lyrics in country songs with male singers were less likely to present women as "empowered, dependent on a man, and instead, they were likely to refer to a woman's appearance" (Rasmussen and Densley, 2017).

Moreover, lyrics in country music songs in the early 2010s differed from those in the early 2000s and early 1990s. The lyrics in the 2010s were less likely to refer to women in some type of less rigid gender roles, including being portrayed as empowered than in the early 1990s and non-traditional roles than in the early 2000s. The same songs were also less likely to refer to women in rigid family roles than in the 2000s. Most recent songs were also more likely to objectify women, such as referring to her appearance in tight or revealing clothing, to her as an object, and the use of slangs.

For instance, songs in the early 2000s were more likely to refer to women in a family role than songs in both the early 1990s and early 2010s. Equivalently, songs in the early 2010s and early 1990s were both more likely to refer to women as objects than songs in the 2000s. These findings propose that changes in country music lyrics do not appear to have changed. Meaning, “lyrics in each of the different decades do not appear to have portrayed women in increasingly rigid gender roles or as more objectified than in the decade immediately preceding it, suggesting that each new era in country music may be distinct in its own right, each representing cultural trends and societal development unique to its respective era” (Dukes, Bisel, Borega, Lobato, and Owens, 2003).

The reduction in references to women in family roles between the early 2000s and early 2010s was because of the changes in songs sung by the male singers and not by those in songs sung by the female singers. The lyrics the male singers have sung in the early 2010s, were more likely to objectify women in numerous ways than were those in previous decades, but the same changes in lyrics were not discovered in country songs sung by female singers, with one exception: Lyrics in songs sung by female singers in the 2010s were more likely to refer to women as distrustful or as cheaters than were songs in the 2000s. These findings illustrate that the most recent era of country music also known as ‘bro-country’ may be more than an anecdotal phenomenon and that the balance of power in country music might have tilted from an older generation of male country stars to the ‘bro-country’ (Rosen, 2013), specifically to the objectification of women.

The current study gave empirical support for this argument, as well as for the lyrics in Maddie and Tae’s hit single, “Girl In A Country Song” released in July 2014, which rose to the top of Billboard’s country chart (Rasmussen and Densley, 2017). Alongside its catchy feminist lyrics conveying the discrepancies between the portrayal of men and women in country music, the song belittles that women in country music “used to get a little respect, now we’re lucky if we even get to climb up in your truck, keep our mouth shut and ride along, and be the girl in a Country Song” (Marlow, Dye, and Scherz, 2015).

Media content studied that gender-based differences in sexuality are similar and consistent with gender stereotypes. Particularly, women are required to concentrate on love and romantic relationships and attain sexually objectified bodies, while men are supposed to focus on sexual behavior. However, there has been less research done on the content of popular music lyrics. Depending on 1,250 songs across five decades from 1960 to 2008, Smiler, Shewmaker and Hearon (2017) have documented the presence or absence of a dating relationship, the word “love” and its uses, sexual activity, and sexual objectification of females and males separately.

The researchers found that songs by female performers contained more lyrical references per line to both love and sex than male performers. They also found that the mean scores indicated that love words appeared three times more frequently than sex words. A later and more detailed study of the Top 100 songs per year from 1959, 1969, 1979, 1989, 1999, and 2009, found that males were more likely than females to include sexual references throughout the time period, although the magnitude of the difference decreased in more recent decades (Hall, 2012). Another study done by Hobbs and Gallup (2017), found that more than 90% of popular music titles contained at least one reproductive message.

The results presented that the majority of popular songs addressed a dating relationship by “71% in every decade” (Smiler, Shewmaker, and Hearon, 2017). Another similar pattern was found for use of the word ‘love’, by “57%, which appeared in a majority of songs for every decade except the 2000s” (Smiler, Shewmaker, and Hearon, 2017). Sexual objectification appeared in a minority of songs by “14%” (Smiler, Shewmaker, and Hearon, 2017), with sexual objectification of female bodies by occurring consistently than the sexual objectification of male bodies.

All these studies demonstrate for a woman to be a part of the music industry, she must be prepared to be objectified and expected to follow what she is instructed to do, to gain recognition for her work.

References

Apuke, Oberiri & Jigem, Lingbuin. (2019). Portrayal and Objectification of Women in Music Videos: A Review of Existing Studies. 2. 160-174

Aubrey, J. S., Hopper, M., & Mbure, W. (2011). Check that body! The effects of sexually objectifying music videos on college men’s sexual beliefs. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 55, 360–379

Brown, J.D., Steele, J.R., and Walsh-Childers, K. (Eds.).(2001). Sexual teens, sexual media: Investigating media's influence on adolescent sexuality. London: Routledge.

Dukes, R. L., Bisel, T.M., Borega, K. N., Lobato, E. A.,& Owens, M. D. (2003). Expressions of love, sex, and hurt in popular songs: A content analysis of all-time greatest hits. The Social Science Journal, 40,643–650. doi:10.1016/S0362-3319(03)00075-2

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward an understanding of women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206

Frisby, C., & Aubrey, J. S. (2012). Race and genre in the use of sexualization in female artists’ music videos. Howard Journal of Communications, 23, 66–87

Hall, P. C., West, J. H., & Hill, S. (2012). Sexualization in lyrics of popular music from 1959 to 2009: Implications for sexuality educators. Sexuality and Culture: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly, 16(2), 103–117. Doi:10.1007/s12119-011-9103-4

Hobbs, D. R., & Gallup, G. G., Jr. (2009). Songs as a medium for embedded reproductive messages. Evolutionary Psychology, 9, 390–416

Janiszewski, C., & Wyer, R. S. (2014). Content and process priming: A review. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24, 96–118. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2013.05

Journal of Media Psychology (2015), 27, pp. 22-32. © 2014 Hogrefe Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000128

Kathrin Karsay, Jörg Matthes, Phillip Platzer & Myrna Plinke (2018) Adopting the Objectifying Gaze: Exposure to Sexually Objectifying Music Videos and Subsequent Gazing Behavior, Media Psychology, 21:1, 27-49, DOI: 10.1080/15213269.2017.1378110

Kistler, M. E., & Lee, M. J. (2010). Does exposure to sexual hip-hop music videos influence the sexual attitudes of college students? Mass Communication and Society, 13, 67–86

Marlow, M., Dye, T., & Scherz, A. (2015). Girl in a country song [Recorded by Maddie & Tae]. On Start here [CD]. Nashville: Dot Records.

Quinn, D. M, Kallen, R. W., Twenge, J. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2006). The disruptive effects of self-objectification on performance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 59–64.

Rasmussen, E.E., Densley, R.L. Girl in a Country Song: Gender Roles and Objectification of Women in Popular Country Music across 1990 to 2014. Sex Roles 76, 188–201 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0670-6

Rosen, J. (2013, August 11). Judy Rosen on the rise of bro-country. Vulture. Retrieved from http://www.vulture.com/2013/08/rise-ofbro-country-florida-georgia-line.html.

Roskos-Ewoldsen, D. R., Roskos-Ewoldsen, B., & Carpentier, F. D. (2009). Media priming: An updated synthesis. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 74–93). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schick, L. “Hit Me Baby”: From Britney Spears to the Socialization of Sexual Objectification of Girls in a Middle School Drama Program. Sexuality & Culture 18, 39–55 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-013-9172-7

Smiler, A.P., Shewmaker, J.W. & Hearon, B. From “I Want To Hold Your Hand” to “Promiscuous”: Sexual Stereotypes in Popular Music Lyrics, 1960–2008. Sexuality & Culture 21, 1083–1105 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-017-9437-7

Ward, L. M., Reed, L., Trinh, S. L., & Foust, M. (2014). Sexuality and entertainment media. In D. L. Tolman, L. M. Diamond, J. A. Bauermeister, W. H. George, J. G. Pfaus, & L. M. Ward (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of sexuality and psychology, Vol. 2. Contextual approaches (p. 373–423). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14194-012

About the Creator

Cozy Queen A’da

Just a simple girl expressing her love for literature 💕

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.