Sophia Hansen-Knarhoi Steps Into the Light With "Undertow"

A debut album where vulnerability, sensuality, and reclamation converge in richly textured sound

With her debut album Undertow, out today, London-based composer and singer-songwriter Sophia Hansen-Knarhoi unveils a world where stark vulnerability meets a brooding, cinematic darkness. Built on the intertwined voices of cello and breath, the record carries an almost tactile sensitivity, drawing the listener into a space where memory and emotion live close to the surface. Undertow emerged from a period of confronting trauma and rediscovering sensuality, a time in which Hansen-Knarhoi allowed herself to sift through the tangled weight of love, loss, and the difficult clarity that comes with healing.

Across the album, she binds the intimate with the corporeal, navigating themes of violation, trust, and the lingering echoes felt by victims of violence against women. The result is a body of work that moves through fear and pain toward an unmistakable sense of absolution. Voice and cello, sometimes indistinguishable, anchor the compositions in a raw and deeply human place, creating an emotional gravity that pulls listeners inward.

Following the release of earlier singles “Crying in Pastel” and “My Mother and Me,” Hansen-Knarhoi shares the arresting video for “All the Things That Aren’t You” today, offering another glimpse into this powerful debut. We spoke to Sophia, below.

Undertow feels both deeply intimate and sonically expansive — how did you navigate balancing emotional vulnerability with such vast, cinematic soundscapes?

To me, the two go hand in hand. These feelings are vast in nature, but the detail is visceral. Space is a key fixture in my work, the expansive arrangements contextualise the intimate focal point, usually the vocals/cello, they tend to have the effect of accentuating the venerability. Negative space is a big part in what creates that intimacy, placing raw performance within minimalist arrangements creates a sense of isolation, a space to think. That’s the place I was writing from with this album. My origins as a composer stem from composing for dance, theatre and film, so the sonic worlds I create are just as important to the process as the singer-songwriter aspect of what I do.

You’ve said the album came from “processing trauma and sensuality.” Can you share what it was like translating those personal experiences into music?

Difficult, sometimes painful, as processing the past tends to be. I found confronting these things through writing to be a space for the range of emotions that come up while processing sexual assault. It led me to delve further into the experiences of the many women around me who have experienced something similar, and how it continually affects their lives in different ways. This album is deeply personal, but also reflects the experiences of many women dealing with the aftermath of violence against women. I hope for the album to be a vessel for healing, through all of the ugly feelings.

The connection between your voice, cello, and body feels central to your work. How do you approach composing through that physical relationship?

It’s honestly about following intuition. Usually I will start improving with cello and humming, breathing, allowing movement to come in. I often try to mimic sounds on my cello with my voice, to see how close and far my voice and cello can sound from each other. Sometimes I will play and sing standing and see how this changes the dynamic between my body and cello. Improvising in this way really helps to facilitate new ideas, and songwriting approaches.

Working with producer Randall Dunn, known for his textured, immersive sound, must have been transformative. What did he bring out of you artistically that surprised you?

Through the process in the studio, we drew out a much darker atmosphere from the songs, something that was established through the lyrics. I came to the studio with just cello and vocals, and some production ideas, Randall and I clicked instantly on this darker direction. Randall really brought this eerie, dissociative atmosphere with his production, whilst maintaining its core minimalist structure. Some of the distinctions within the record became more apparent; finding the tension between directness of lyrics, and estrangement of the sound worlds they live in. For example the vortex arrangement of ‘Crying In Pastel’, with its confronting lyrics. I think a lot of the studio process with Randall was focused on accentuating what was already within the work, extrapolating the arrangements, and creating mood.

“All the Things That Aren’t You” channels rage and recognition. Was it cathartic to give that anger such a powerful sonic form?

This song is full of feminine rage. A moment of recognition of mistreatment, a resounding fuck you to a man complacent. With this epiphany comes a collective rage for women, rage at the results of a patriarchal, misogynistic system that seeps its way into our relationships, tangled up in love, desire, care, expectations. This was one of the most difficult vocal parts to record, with rage overriding technical accuracy. Randall and I came back to it a few times before we found its final form.

You use field recordings, like the storm that became part of “All the Things That Aren’t You.” What draws you to blending natural sound with your music?

I grew up in Western Australia, spending my childhood surrounded by nature. It feels to me the most safe, calming place to be. Nature feels inherently feminine to me, having been tied together throughout history in literature, mythology and many cultures. The feminine and the body are deeply embedded into my work, through my lyrics, and the relationship between my voice and cello. Nature grounds the work and looks outwards, it places these feelings in the world. The compositional properties of field recordings are endless, with nature as a foundational sonic element, the work emerges through freeform, intuitive explorations of sound and space.

You’ve described Undertow as existing between fear, pain, and absolution. What does healing look like for you through music?

I think it's the kind of expression of feeling that can’t be found through conversation that is so healing. The way that words and sound converge on an idea, create a new sense of clarity in the writing process, a catharsis through the emotionality of a phrase sung, the presence of touch and timbre as I improvise on cello.

Folk storytelling seems to anchor your songwriting, even as you experiment with abstraction. Who or what has shaped your sense of narrative in song?

Folk music relies on the oral transmission of song, and many, like legendary folk artist Peter Seeger believe that writing these songs down takes away their power and purpose. In an interview with Paul Zollo, Seeger states in reference to a songbook he learnt from in school; “And the conclusion was that they hoped people in school could learn a folk song off the page of a book. You can’t do that. You’ve got to hear the style. It wasn’t enough to read the skeleton of the melody on the page. You didn’t get the delicate subtleties.”1 I believe this to be true in my approach to music making and collaborating. To understand the song, one must listen to the delivery, feel the weight of the words, and understand the elements and intricacies that make the song what it is.

He states Folk music is “a process by which ordinary people take over old songs and make them their own. They don’t just listen to it. They sing it. They sing along with it. They change it.” This album was written and realised in a studio setting. With my live set of the album, I was able to expand on and translate their sound worlds into a live context. I am a big believer in giving myself creative freedom to adapt my songs into a performance context and realising them in a different way. The ability to write songs that can be adapted in many ways to fit different contexts is why I call myself a folk artist. The songs I write are written to be changed and moulded into many new versions of themselves.

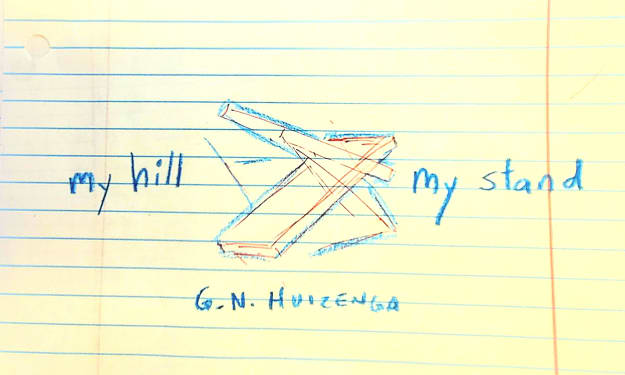

My origins as a composer seem to coalesce around my early teens, when I would sit in my bed at night after school and task myself with writing at least one poem a night. It was in these moments that I built the foundations of my voice, my storytelling, however musical or unmusical they were at that stage. I was creating for myself, stringing together words I believe I didn’t want anyone to read at the time. I would hide them away in my drawer, excited to do it all again the next night. Once I had settled into this ritual, I began singing the words out to myself. I would create melodies for my words, sometimes with a squiggle here and there to remember where my voice went on certain words. Once I had these melodies, I would sing them to myself most nights to try and imprint them into my head. Some of them are still there now. I continue to compose in this way, though I am now informed by a world of musical knowledge that little me in my room didn’t have the faintest idea of. This aural tradition, I have found, is my truest form of creative expression.

Nature — particularly the landscapes of Western Australia — feels like a recurring character in your work. How does the environment shape your emotional or creative language?

It continually informs both my emotional and creative language. On a personal level, I spend time in nature to process my thoughts and feelings, however menial. I am quite aurally sensitive to certain environments, so a natural soundscape really eases my senses. Creatively, I allow myself to be engulfed by nature perhaps more than I do music. I take inspiration from nature like I would any other art form. I go on sound walks often. Now living in London I am enjoying the cacophony of nature and human infrastructure, perhaps this will inform whatever I make next.

Now that Undertow is out in the world, what emotional space are you inhabiting as you look ahead to what’s next?

I like to take my time in creating, I love to mull over projects and their tangents for a while before embarking on something new. Cross-art form collaboration is a big passion of mine, so perhaps something different, someone else’s story maybe the next project.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.