Scientists Observe a Hidden Water Reservoir Beneath the Desert Larger Than Expected

Groundbreaking discovery reveals vast underground aquifers where deserts were once thought bone‑dry—reshaping our understanding of Earth’s water resources

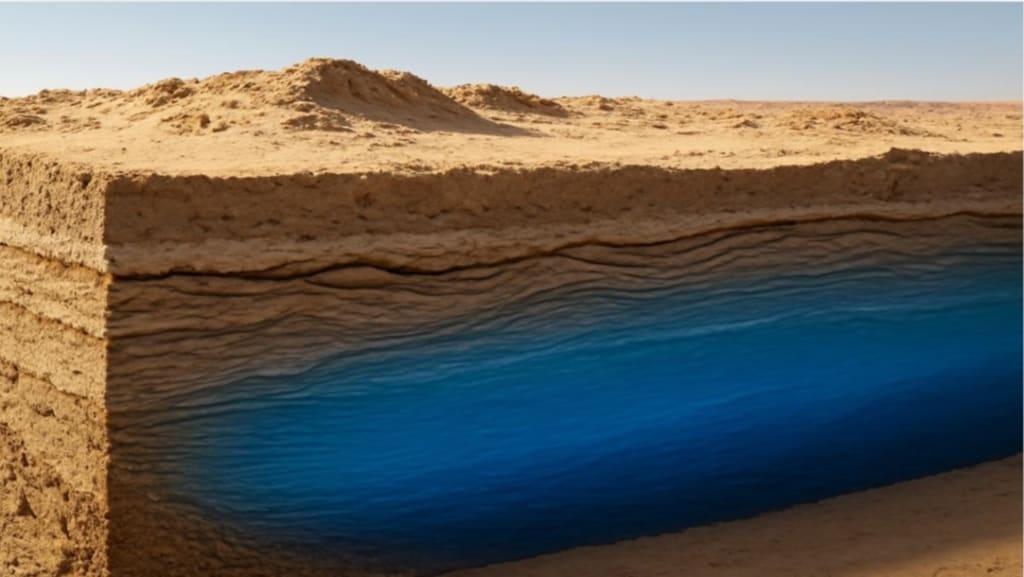

In what scientists are calling a surprising breakthrough, researchers have identified a much larger‑than‑expected reservoir of water hidden deep beneath a desert region, challenging long‑held assumptions about how arid landscapes store and cycle water. Far from being lifeless expanses of sand and rock, some deserts conceal complex underground water systems that could have big implications for water security, climate science, and our understanding of how rain and ancient climate events shape Earth’s interior.

A Desert’s Secret Beneath the Surface

For decades, deserts have been viewed as water‑scarce environments, with sparse rainfall and little surface water. Yet the new research shows that hydrologists and geologists were underestimating the scope of subsurface water systems. Using a combination of seismic surveys, satellite gravimetry and electromagnetic imaging, scientists detected layers of saturated rock and sediment stretching for hundreds of square kilometers beneath the desert floor—a volume far larger than previous models suggested.

Where older theories painted deserts as static and dry, emerging data reveals a dynamic picture: multiple aquifers stacked at different depths, some recharged by rare but intense storm events, others holding water that may have accumulated for thousands—or even tens of thousands—of years.

How the Hidden Reservoir Was Found

The breakthrough didn’t come from just one method—it was the intersection of cutting‑edge technologies that made the hidden reservoir visible:

Seismic imaging measured how sound waves travel through subsurface rock. Water‑saturated layers show distinct signatures compared with dry stone, allowing researchers to map the extent of the aquifers.

Gravimetry detected subtle variations in Earth’s gravity field, which can hint at lower‑density materials like water holding zones deep underground.

Electromagnetic surveys picked up on how underground materials conduct electricity—water and wet sediments produce different signals than dry rock.

Together, these tools helped construct a three‑dimensional model of the subsurface: not a simple dry loaf of rock beneath the dunes, but an intricate layered system where significant amounts of water are locked away, often under confining rock and untouched for generations.

A Reservoir of Many Ages

One of the most intriguing aspects of this discovery is the range of water ages. Shallow aquifer layers appear to be replenished by episodic rainfall events—uncommon in desert climates but occasionally intense enough to force water deep into the ground. Meanwhile, deeper layers contain water that predates modern climate conditions, possibly trapped since wetter eras in Earth’s past.

Researchers estimate the subsurface water ranges from decades old near the surface to thousands of years old in deeper strata, preserved by heavy mineral seals and compacted sediments. These ancient reserves provide clues about how past climates influenced water distribution—and how deserts evolved from wetter landscapes over millennia.

Why It Matters: Water Security and Sustainability

Although the newly discovered reservoir is not directly equivalent to liquid lakes or rivers that could be easily tapped, it changes how scientists and policymakers think about water resources in arid regions. With global climate shifts increasing droughts and water scarcity, understanding all available water sources, including deep aquifers, is critical for long‑term planning.

Experts caution that extracting water from deep desert aquifers is not simple. The water is often trapped under confining rock layers, and tapping it could disturb delicate geological balances. Yet the mere existence of such reserves suggests that deserts are more hydrologically complex than previously recognized, offering new avenues for research into sustainable water management.

Broader Scientific Implications

Beyond water supply, the discovery reshapes our understanding of the global water cycle. Traditionally, hydrologists focus on surface water, atmospheric moisture, and near‑surface groundwater. But vast reservoirs like this highlight that subsurface water systems are active parts of Earth’s hydrology, moving slowly through rock and sediment layers far below the surface.

This insight also echoes findings from other parts of the world. For example, massive underground aquifers have been found in the Oregon Cascades, holding volumes of water more than twice the capacity of Lake Mead—a reminder that groundwater systems can be enormous and previously overlooked.

Additionally, studies have pointed to even deeper water reservoirs locked inside Earth’s mantle, in minerals that could collectively hold more water than all the planet’s surface oceans combined. While those deep reservoirs are a different phenomenon, they underscore the hidden complexity of Earth’s water storage and distribution.

What’s Next for Research?

The discovery underlines the importance of multi‑disciplinary science. As remote sensing, geophysics, and geology tools advance, researchers expect more subsurface water systems to be mapped—and with greater precision. Future work will focus on dating the water more accurately, determining its chemistry, and exploring how connected these aquifers are to surface conditions.

Understanding these hidden reserves could open new strategies for dealing with drought and water scarcity—but also raises questions about the ethical, environmental, and technical challenges of tapping ancient, fragile water stores. And it highlights that even some of the world’s driest landscapes may still hold secret lifelines beneath their sands.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.