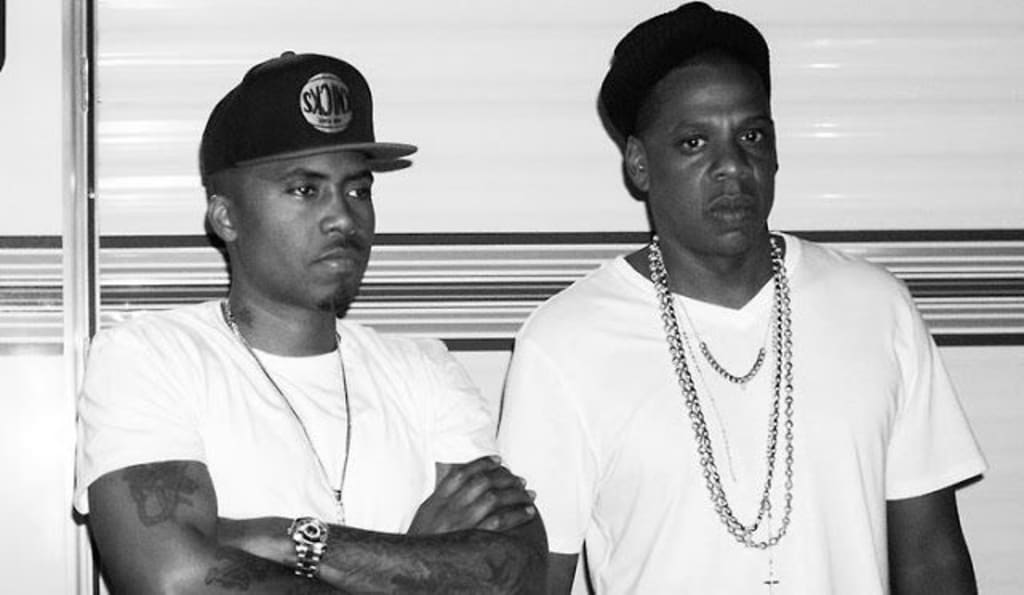

Nas & Jay Z- 21st Century Booker/Du Bois

A deep dive into hip hop rivalry, history & politics

A deep dive into Hip Hop rivalry, Jay & Nas and the history it represents & how it's a mirror to what is going on in the macro verse of social media & politics.

"Success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has overcome" – Booker T Washington

The rivalry between Nas and Jay-Z are trodden territory, but for the sake of hip-hop novices a brief retelling is in order. Hip hop is a culture consumed by competition. In its formative stages, DJs vied for sound-system supremacy. The duel was literally one of decibels. At a later stage in the game, scratching techniques took center stage as turntablists took turns awing audiences with their hand wizardry. Before the public got hip, b-boying was mistaken for fighting. The rivalry between crews was just as real as any street beef, the combat just as aggressive as an urban brawl and the objective was equally unambiguous: win. Graffiti’s evolution relied solely on its competitive impulses. From simple black-and-white letter tags to bubble letters to intricately obscured car-length burners, the goal of the artist was at once ubiquity (“going all city”) and individuality (authoring a distinct style). The MC’s thirst for lyrical supremacy has spawned two distinct spheres of combat: the freestyle and the wax battle. The former is truer to rap’s origins. Two rival rappers take turns rhyming off the top of their heads before an audience. The objective is to cleverly assault and insult the competition a la the Dozens, but on beat. The rapper whose rhymes draw the most praise from the audience is declared the winner. More often than not, however, the freestyling technique has little to no bearing on commercial viability, which is largely dependent upon factors that have little to do with lyrical craftsmanship. Which brings us to the wax battle. Typically, this style of competition only registers in the cognoscenti’s consciousness if both rappers have both commercial and cultural credibility. Usually, the “beef” is preceded by some perceived slight, disagreement or falling out leading to one rapper taking direct or indirect stabs at the other on record. Once the response is made, the battle officially begins. Some trace the roots of the rivalry between Nas and Jay-Z back to the mid 1990s; I’m not one of them. The stage wasn’t really set for a conflict until BIG was murdered and Jay-Z asserted rights of ascension. BIG’s music was triumphantly materialistic. It celebrated money, power and status. In the post-Biggie world, Jay-Z steered his music and his image to fill this void. Creatively speaking Jay-Z and Nas dealt with BIG’s death very differently. Jay-Z sought to keep BIG alive through his art and to use his life and his work to elevate his own stature; Nas idealized BIG’s life and death. In the song, “We Will Survive” from his third album, I Am..., Nas compared Biggie to God (“You was like God in the form/Of Allah”). Earlier in the song he rapped,

“Now competition is none/Now that your gone/And these brothas is wrong/Using your name in vain/And they claim to be New York’s King?”

In one sense the lines can be read as a swipe at Jay-Z; in another they reveal Nas’s idealism. The thought of capitalizing off of his friend’s death offended his code of ethics. Conversely, Jay-Z saw it as his obligation to take over for his fallen friend. Both believed they were honoring a comrade. Their conflicting world views vis-à-vis BIG—idealism versus materialism—were, I believe, the ultimate source and thrust of their rivalry.

A Ship Passing

I want to say this now and be done with it: By placing Nas and Jay-Z at these extremes I’m not saying they didn’t share qualities. Part of what makes any conflict between exceptional personalities compelling is that they are a lot alike. More than anything else, the qualities they share are the ones that stir their rivalry in the first place. They were both exceptionally gifted artists. They were both children of the modern urban ghetto. They were both veterans of a ruthlessly competitive business that routinely disposes of rappers after a mere handful of years. These were ingredients that made the Hip-Hop nation hold its breath when Jay-Z unleashed “Takeover” in the summer of 2001. In rap, the typical “dis” record seeks to ridicule and belittle the target by questioning his MC skills, credibility and sexual virility. “Takeover” covered each of these bases and then went on to attack Nas’s commercial productivity and entrepreneurial savvy before finally belittling his propensity to infuse his music with “knowledge” (re: black consciousness). On his follow-up to 2002’s “Blueprint II,” Jay-Z returned to his conflict with Nas, fleshing out this particular gripe:

Can’t you see that he’s fake/The rap version of T.D. Jakes/ Prophesizing on your CDs and tapes/Won’t break you a crumb off the little bit that he makes/And this is with whom you want to place your faith?/I put dollars on mine, ask Columbine/When the Twin Towers dropped, I was the first in line/Donating proceeds off every ticket sold/When I was out on the road, that’s how you judge Hov, no?/Ain’t I supposed to be absorbed with myself?/Every time there’s a tragedy, I’m the first one to help/They call me this misogynist but they don’t call me the dude/To take his dollars to give gifts at the projects/These dudes is all politics, depositing checks/They put in they pocket, all you get in return is a lot of lip/And y’all buy that shit, caught up in the hype/‘Cause the nigga wear a kufi, it don’t mean that he bright/‘Cause you don’t understand, it don’t mean that he nice...

For Jay-Z, the conscious/political persona Nas was being given credit for reflecting in his art was not as authentic as the actual help he was giving to those in need. He’d donated concert proceeds to the victims of Columbine, given a million dollars to the 9/11 Fund, and generously funded his foundation’s inner-city youth initiative. And yet Nas was the one given credit for being a socially conscious artist.

The Washington Vs Du Bois Effect

Booker T. Washington was disparaged by other black leaders because they thought his politics were too conservative; he too gave generously if not quietly to causes that forwarded the interests of the race. Washington was criticized for being too cozy with white supporters and for surrendering the struggle for civil and political rights for the pipe dream of material prosperity. Jay-Z was very much in the materialist tradition of Washington. Nas’s revolutionary rhetoric was as meaningless and absurd to him as the idea of the “lone black boy pouring over French grammar amid the weeds and dirt of a neglected home” was to Washington. A Familiar Feud Sticking with the spirit of the connection between Jay-Z and Booker T. Washington, Nas’s response to Jay-Z’s taunting “Takeover” bore a remarkable resemblance to W.E.B. Du Bois’s response to Booker T. Washington’s biography, Up From Slavery. Like much of Jay-Z’s most popular work, Up From Slavery was what Du Bois biographer David Levering Lewis called “vintage American: faith in God and hard, hard work overcoming bleakest adversity.” The book was published in 1901 and immediately became a “stupendous success,” but Du Bois saw it and its author as increasingly onerous burdens on the progress of the race that “threatened to over-whelm perspective and proportion.” Prior to this, Du Bois had been willing to watch his future rival from the sidelines. But after the book’s publication and in light of a series of slights Washington slung Du Bois’s way—he routinely ridiculed the frivolousness of Latin, French and Philosophy—Du Bois could no longer hold himself back. As Dr. Lewis put it, “Du Bois felt mocked in the very center of his considerable self-significance.” Du Bois authored a scathing review of the book rebuking the Tuskegee president at a time when the latter’s authority in the black community was virtually unquestioned. In his review, Du Bois artfully dismantled the popular view of Washington’s “originality” and “sophistication.” The review later appeared in expanded form inside the pages of The Souls of Black Folks, the book that fundamentally altered the African-American literary canon and established Du Bois as Washington’s rival and the voice of the Talented Tenth. Written under the title, “Of Mr. Washington and Others,” the essay read much like an eloquent “dis” record authored by a rap rhetorician. It demystified Washington’s genius by showing his linkage to earlier generations of accomodationist blacks. Du Bois acknowledged that Washington grasped “the spirit of the age...dominating the North” by learning “the speech and thought of triumphant commercialism, and the ideals of materialistic prosperity.” But there had also been 99 lynchings in 1901 and by then Du Bois had conducted his groundbreaking study of Philadelphia blacks and seen the subhuman conditions throughout the South with his own eyes. As a matter of necessity someone had to speak for the people and against the views that Washington was advancing. Up until the point Souls appeared, Du Bois had primarily been a scholar. He wasn’t interested in leading a movement. Nonetheless, he felt duty-bound to stand up against the ideas Washington represented in white America’s mind. In so doing he “made up his mind to measure his beliefs against those of Washington.” Casting Washington’s philosophy as one that “practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races” by ignoring the “higher aims of life,” Du Bois made his case for what would in the years to come be known as the modern civil rights movement. Even though Du Bois wasn’t entirely opposed to Washington and didn’t confuse him for the race’s real enemy, he felt Washington’s misguided philosophy coupled with the financial and social support he had among whites, made his leadership particularly dangerous and in need of internal criticism. According to Du Bois’s reading of history, Booker T. Washington, unlike previous leaders, had not been chosen by the race but by elite whites whose values he reaffirmed.

Exactly 100 hundred years after the Du Bois-Washington conflict began a war of words between Jay-Z and Nas gripped the Hip-Hop nation. And while most fans and followers characterized it as simply the greatest rap battle of all time, the emphasis on the records—who won, who lost—obscured a more significant conflict within the Hip-Hop generation. The battle between Jay-Z and Nas, I believe, tells us as much about the dilemma in young, marginalized black America at the turn of the 21st century as the conflict between Du Bois and Washington tells us about the dilemma in an oppressed black America at the turn of the 20th century. In his essay on Washington, Du Bois wrote, the “attitude of the imprisoned group may take three main forms—a feelings of revolt and revenge; an attempt to adjust all thought and action to the will of the greater group; or, finally, a determined effort of self-realization and self-development despite environing opinion.” Depending on the epoch, the “influence of all of those attitudes...can be traced in the history of the American Negro, and in the evolution of his successive leaders.” Washington represented the season of accommodation following a period of prolonged protest, and amid the rising sentiment in post-Reconstruction era America that the country had expended too much energy on the “race question.” He didn’t use his platform to speak out against violence and other forms of injustice; rather, he relied on his own success story to insist the race could rise if only it was was willing to put forth the effort. Jay-Z followed the blueprint laid down by Booker T. Washington. At a moment when America was going through one of its cyclical periods of race weariness (when the nation becomes exhausted with reports of black homicide and black discontent), rap, as potent a reflection of black American life as every there has been, became remarkably accommodating to white America’s race fatigue. Essentially the music gutted itself of political substance to get ahead in the world. It reveled in its own destructive behavior, silenced its positive messengers and applauded its own rendition of the “bootstrap” parable. White America in turn rushed to the stores in record numbers. Suddenly, it could listen to young black men describe life in the ‘hood without feeling fearful or guilty, let alone like it had any responsibility to use its privilege to help change the conditions that produced those ghetto tales. Pre-millennial Tensions Prior to the release of his fifth album, Stillmatic, there were some genuine questions about who Nas was and what he stood for. He seemed unclear about the role he wanted to play in hip hop and his third and fourth albums (I Am... and Nastradamus) reflected that confusion. But we have to keep in mind the commercial climate in which both of those albums were released. In 1998 hip hop had officially become a commercial phenomenon. Suddenly, instead of obligatory two-year lapses between studio albums, artists—DMX for example—were releasing two albums in a single year, double albums, even triple albums. It was as if they—record companies and artists alike—knew the good times couldn’t last and were determined to squeeze every dollar out of the market before the well ran dry. As records poured into stores, the excesses of the age—the materialism—became par for the course. Everyone was doing it: trying to get paid. Nas was no exception. In 1999 he released two albums in the span of eight months. The first, I Am..., strove, at times, for social relevance. “I Want to Talk to You” was a direct assault on indifferent elected officials; “Ghetto Prisoners” sought to rile the dormant spirit of revolt in the ‘hood; and “We Will Survive” strained to rally and inspire the Hip-Hop nation through Nas’s personal tributes to Tupac and BIG. As ambitious as each of these songs were conceptually, they were lyrically stilted and sonically mediocre. The second album, Nastradamus, lacked the ambition of its predecessor and was marred throughout by uninspired faux-prophecy. By 2000 the Nas that had once seemed so promising, so gifted, was fast-becoming another marginal MC with an overinflated ego living off of his reputation. That is, of course, one reading based largely on observation. Looking back over I Am... I was struck by Nas’s repeated references to historical events; his searching spiritual questions; his anxieties about black America’s future; his obsession with ancient civilizations, particularly Egypt; and his multiple mentions of God, Allah and Christ. As poorly formed as many of these thoughts were, their disarray was indicative of the pre-millennial paranoia that seems so distant now but felt so inevitable at the time.

Americans really did believe the world was going to end when the clock struck 01/01/00. Computers were supposed to crash. The exchange markets were supposed to collapse. Days before the millennium everyday Americans were rushing to Walmart to stockpile food and other supplies. People were buying bomb shelters. I even recall a news story about a man burying cash underground. Although Nas’s execution failed to live up to his ambition, he was an artist trying to straddle the fence between the commercial imperatives and creative impulses tugging at the soul of hip hop. In fact, these two albums might be better viewed as representations of what was taking place on the street and in the culture at the turn of the century. As the millennium approached, the term “new world order” was rolling from the tongue of every “conscious” brother or sister in the street. Talk of “third eyes” and “unseen hands” dominated hip-hop ciphers. Author Jeff Chang remembered “conspiracy theory laden books…being circulated throughout the nation.” Books like Behold the Pale Horse found their way into my hands. Others like the COINTELPRO Papers were examined closely in basement study sessions I attended. For many of us involved in these heady, if not paranoid, discourses, the pieces to the puzzle were all around us. Third eyes on dollar bills; presidential speeches; ancient architecture; masonic-inspired urban design. In a sense, while Nas was busy trying prepare us for the new world order

(“And y’all combining all/Countries/We gonna do the same/Combine all the clicks an make/One gang/ It ain’t a black and white thing/It’s to make a change/Citizens on a higher plane),

Jay-Z was flooding the clubs with a string of catchy songs that did anything but force us to think about or prepare for the future that greeted us on September 11, 2001.

Carry On Tradition Metamorphosis

Within two months of the September 11th attacks, the USA Patriot Act had been rushed into law and a war with Afghanistan had been launched. Hundreds of immigrants had been rounded up and thrown into jail. There they languished for months, and in some cases years. Hate crimes against Arab-Americans or those perceived to be of Muslim descent skyrocketed. Fear of the “other” swept across the United States. Overnight freedoms we had once taken for granted were placed in jeopardy. Even as the Bush Administration and corporate America orchestrated a “Keep America Rolling” campaign to spark an already stalled economy, Americans couldn’t escape the unfamiliar state of panic. The veil had been lifted. Our cherry had been popped. We were suddenly part of the world. As winter set in and the new permanent state of emergency became a reality, Nas released Stillmatic. A century earlier Du Bois worried that his rival was trading black America’s soul for a stake in the emerging industrial economy. It was this danger of reducing human beings to economic objects he was hoping to thwart with his pen. By the same token, “Ether,” Nas’s response to Jay-Z and the values he represented, (“What’s sad is I love you ‘cause you my brother/You traded your soul for riches”) was his way of challenging the materialistic values Jay-Z represented and the direction they were taking the culture. In an interview he gave around this time he elaborated on the point he was making in the song. “Any nigga can shine,” Nas said. “That’s the last thing I’m worrying about. I shine without jewelry. If I’m gonna use this time, I’m gonna use it for something real.” It was at this point, with his back against the wall, much as Du Bois felt his was, that Nas began defining himself anew. With his reputation, livelihood and values on the line, he was forced to do exactly what Du Bois had done: define his own beliefs against those espoused by his rival. Released at the tail end of 2001, Stillmatic would re-awaken the Hip-Hop generation to many of the themes and values that had made it the voice of disenfranchised youth the world over. In an industry notorious for one-hit wonders and overnight meltdowns, Nas’s comeback was noteworthy. In a culture that generally discards its best and brightest as a matter of course, his comeback was unprecedented. In a commercial environment stagnated by recession and rampant pirating (bootlegging and illegal downloading), his comeback was nothing short of astonishing. But it was the atmosphere of anxiety and patriotism (remember all of the flags) permeating the airwaves and choking off the voice of dissent that made the success and impact of an album that was neither anxious nor “patriotic” truly remarkable. Stillmatic re-kindled the tradition and spirit of black protest and power that had been missing from mainstream (or relevant) hip hop for several years and revived the age-old dilemma between the competing world views in black American life: the Nightmare and the Dream. It’s hard to dispute that The Blueprint (which though released on 9/11 still managed to sell nearly 500,000 copies in its first week) was the soundtrack of the season. Backed by the usual arsenal of self-indulgent, catchy, clubby singles (“Izzo (HOVA),”—yet another ghetto anthem inspired by his rags to riches story—and “Girls, Girls, Girls”—a soulful celebration of the spoils of stardom—led the way this go-round), Jay-Z’s solipsistic pop songs backed by slick, colorfully adorned music videos were the perfect tonic to the sobering reality the post-9/11 world presented us with. Coupled with the album’s stirring soul samples (The Jackson Five, Bobby Blueband, David Ruffin and Al Green), the The Blueprint’s deeply personal sensibility massaged a collective nostalgia the entire nation seemed to have for a simpler (if not romantically tinged) time. In short, at least some of the The Blueprint’s brilliance must be attributed to the melancholic emotions it evoked at a tender, precarious moment in the nation’s history. But if The Blueprint belonged to the pre-9/11 world of private engagement, an epoch suffused with (or maybe mired in) our national obsession with the self, Stillmatic, from beginning to end, belonged to the post-9/11 world of public engagement. Nas aggressively and defiantly wrestled with America—locally, nationally and internationally—as only a true American patriot can. The album was idealistic in intentions and ambitious in scope; unflinching in timbre and apocalyptic in tenor. The immediacy and urgency of both “Got Yourself A…” and “One Mic” managed to transmute art into the “promise...of spiritual and social redefinition.” When on “Got Yourself A...” Nas rapped,

“Yo, I’m livin’ in these times/Behind enemy lines” or “Me and Tupac was soldiers of the same struggle,” or, on “One Mic,” “There’s nothing in our way/They buss, we buss/They rush, we rush/Led flyin’, feel it?/I feel it in my gut that we take these bitches to war/Lie ‘em down/‘Cause we stronger now my nigga/The time is now…,”

he was reclaiming the tradition of resistance that hip hop was founded upon. By transforming his voice into a weapon or resistance, Nas brought the culture back to the site of the struggle—the ‘hood—that never disappeared but had been blurred, fragmented and disconnected from the historical continuum of revolt reaching back to Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey and Gabriel Prosser. While the spirit of resistance was not new to Nas’s artistic palette, what marked Stillmatic as a progression was consistency and coherency. In the past he had employed militant terminology, but the art itself had failed to fully project the immediacy and urgency that would have made it relevant and effective. With Stillmatic Nas reached a level of creative maturity that allowed him to own the legacy of consciousness that he had previously dabbled with superficially and caused many a critic, Jay-Z in particular, to question the authenticity of the social and spiritual ideals he rapped about. On one of the album’s most confessional songs, “You’re Da Man,” Nas opened up about his journey from Darkness:

Wait a sec, give me time to explain/Women and fast cars and/ Diamond rings/Can poison a rap star/Suicidal/High, smokin’ so much lie/I saw a dead bird flyin’/Through a broken sky. to Light: My destiny found me/It was clear why the struggle was so painful/ Metamorphosis/This is what I changed to/God I’m so thankful.

The “metamorphosis” was eloquently evident on “2nd Childhood,” a pensive and painfully honest critique of grown ghetto dwellers who fail to change their ways with age. The song managed to be part elegy for those beyond redemption and part cautionary tale for those following a similar path of destruction. More than anything, it revealed a courageousness often missing from hardcore rappers who shy away from criticizing their own for fear of alienating the ‘hood or participating in the ghetto-bashing often directed at the ‘hood by outsiders. The honest self-criticism (of both himself and the ‘hood that he so intimately and loyally identified with) set the stage for the unremitting castigation of post-9/11 America that dominated the last third of Stillmatic. At a time when all too many of us were trumpeting our war horns or at the very least hiding our discontent from public view, when pop artists were censoring themselves for the sake of patriotism not to mention record sales and corporate sponsorships, Nas was one of the few relevant artists willing to express dissent. On “What Goes Around” he boldly proclaimed himself a “George Bush Killer to George Bush kill me” when Bush’s approval ratings were at an all-time high. On “Rule” (a reprisal of his hit single “If I Ruled the World”), he challenged a world headed for war to

“call a truce, world peace/Stop actin’ like savages/No war, we should take time and think/The bombs and tanks makes mankind extinct.”

On “My Country” he spoke for the thousands of disenfranchised and alienated youth either being warehoused in prison or shipped off to become war fodder.

A Re-Awakening

It’s important to understand that Stillmatic wasn’t a safe album. But it’s also important to understand that it was an album the culture needed, an album America needed. The drumbeat of the Iraq War was only beginning to echo in the distance. We could still block out the new global reality that met us at airports across the country with Jay-Z’s “I Just Wanna Love U.” But a great many of us knew that the America everyone else had awakened to on September 12th had been in full effect for black Americans for centuries. The terror, the fear—all of that was part of day-to-day existence in every ghetto across the globe. Even Jay-Z expressed his ambivalence about September 11th. “I’m really sick,” he said shortly after the event, “Same time, this is still a land that’s not really for my people, and I can’t just forget that.” As ambivalently as he felt about being black, from poverty and being American, Jay-Z chose the path of least resistance. This isn’t a judgment of his character, merely a characterization of his judgment. It wasn’t in his interest to infuse his art with his ambivalence; instead he chose to affirm and reaffirm (again and again) the American Dream myth. Nas, meanwhile, sensed the undercurrent of dissent and rage that was simmering below the surface. It took another two years and the unjustified invasion of Iraq to really galvanize Americans, and then only because the voice of dissent was in vogue. But among those who make up the Hip-Hop generation, uncertainty was alive well before that. We watched the Twin Towers burn and the Pentagon fold and we thought to ourselves, this is a tragedy, but it should also be a wake-up call to a sick society. The destruction that occurred on 9/11 was, for us, the opportunity to rebuild the country, to choose a different path. Stillmatic was the album that articulated the Hip-Hop generation’s post-9/11 ethos. It was our pain and frustration; our desire to be fully American, but not to abandon our roots or responsibility to oppressed people the world over who are linked to our struggles. The safe artist would have side-stepped the thankless task of voicing dissent in a climate of intolerance; he or she would’ve turned a blind eye to the poverty, ignorance and disease most live in if it meant jeopardizing their own comfort. With Stillmatic Nas took the risk of a lifetime and in so doing placed himself on the continuum of resistance and protest that characterizes the best of black creative leadership. Stillmatic was a gamble. Following the decline of Public Enemy and Ice Cube, the hip-hip industry had changed dramatically. Social consciousness was routinely marginalized. Artists like Mos Def, Talib Kweli, Dead Prez and Common had solid fan bases among bohemian, urban-eclectic, alternative and underground audiences, but their music rarely reached the hardcore and street listeners. Ultimately the “socially conscious” MC suffered from market marginalization. Just as certain artists were marketed as “gangsta” or “street” or even “pop,” MCs with a message were marketed as “conscious,” making them anathema to hip hoppers who liked their music raw, uncut, graphic and, above all, real. These were quite often listeners who first tuned into hip hop in the early 1990s when MTV was beginning to notice the link between the rebellion reverberating from grunge bands like Nirvana and Pearl Jam and the outlaw aesthetic of mega-popular rappers like Snoop (Doggy) Dog and Cypress Hill. For these listeners hip hop wasn’t about uplifting a degraded culture; it was about being superficially and safely down with a side of American life they would never know personally but were nonetheless fascinated by. Put differently, the droves of mainstream consumers (white, brown, yellow, black) who flocked to hip hop in the mid-90s weren’t interested in or concerned with uplifting the ghetto. Stillmatic was the first album since Tupac’s Me Against the World and The Seven Day Theory to successfully channel sustained socio-political rage into commercially relevant art. It is no great surprise, then, that after Stillmatic Nas ascended to Thug Revolutionary, a rank that Tupac had singularly symbolized in our generation’s popular imagination. As Dr. Dyson points out repeatedly in his biography, Tupac’s death elevated him to “ghetto sainthood,” ultimately creating a blueprint for others who followed him. Several rappers, including DMX, Ja Rule and 50 Cent managed to physically and emotively appropriate the “thug” aspect of Tupac’s mythology, but only Nas, with Stillmatic, was able to fuse the thug with the revolutionary thinker engaged in the struggle to raise his people. In many ways, in fact, Nas’s career following Stillmatic evolved the ideology of resistance well beyond anything ‘Pac lived long enough to do.

Beyond Stillmatic

In between the release of Stillmatic and his next studio album, God’s Son, Nas released a collection of previously unavailable songs. Titled The Lost Tapes, the album cobbled together songs that had been scheduled to be on I Am... before leaking onto the internet, and other more recent songs that hadn’t made it onto Stillmatic. Better than any song Nas had released up to that point, “Black Zombies” articulated the world view that would come to dominate his post-Stillmatic work. Woven around the melodic hook, “Walkin’, talkin dead, though we think we livin’/(Black Zombies)/We just copy-cat/Followin’ the system,” the song was an impassioned, self-reflective critique of the problems plaguing the black community: prejudice from outside

(“You believe when they say we ain’t shit, we can’t grow/All we are is dope dealers and gangstas and hoes;”) economic insolvency (“What do we own? Not enough land, not enough homes, not enough banks/To give my brother a loan. What do we own? The skin on our backs/We rent and we ask for reparations”); ignorance (“We trapped in our brain, fuck behind bars/We’ve already gone insane”); and dependency (“I’m a Colombia record slave/So get paid/Control your own destiny, you are a genius/Don’t let it happen to you, like it did to me/I was a Black Zombie”).

From this point forward Nas’s body of work reflected a sense of social responsibility bred from a deep, committed love of people—the kind that refuses to shy from self-examination or from the criticism that it might elicit from others. It was this willingness to examine, expose and potentially alienate in the name of love that made his work compelling On “Black Zombies” he acknowledged, as Malcolm had to, his own ignorance, that for a time he had been sleepwalking through life. That acknowledgment was crucial because it revealed his humility. That humility was what lent his criticism of the community legitimacy. Revolutionaries must risk being unpopular. By definition they undermine the status quo. In hip hop the “status quo,” for the previous decade, had been self-indulgence, escapism, ghetto-glorification and absolute indifference. Up-and-coming artists understood that the industry was only looking for the image it could sell to mainstream America. Talent, creativity and conscience all took a back seat to the “thug” image. In fact, creativity and consciousness were frowned upon. As Jay-Z once rapped, it was better to simply “stick to the script.” If we limit our understanding of a “revolutionary” to one who seeks to fundamentally transform the economic order by overthrowing the government, then certainly the image of Nas seated in a wicker throne holding a staff and a pistol beside a similar photo of Huey Newton inside the pages of his God’s Son album seems absurd on every level. But, if we acknowledge the state of confusion and despair in large segments of 21st black America, and the role black entertainers and athletes play in perpetuating (by silence; by confusing individual advancement with group advancement) that sorry condition, then the audacity of a world-famous rapper aligning himself with Huey Newton bears noting. What was his intention? Why did he feel compelled to make such a bold and potentially hazardous statement? Huey and the Panthers saw themselves as the vanguard of the global liberation movement. The world was changing and, because they were at center of the Western empire, they saw themselves at the forefront of that change. Fundamentally, however, the Panthers stood for black self-help and community control. They understood that revolution was a process and that people have to be prepared for it. That preparation could only come through education and consciousness-raising. Only when people were aware of their condition and the role capitalism played in perpetuating it would they be willing to revolt. The thing is people will never be ready if no one challenges them to open their eyes. The knock against Nas, and Tupac before him, was that they were not “real” revolutionaries because they weren’t anti-capitalist. My contention is that

1) the audience Nas was addressing was in no position to even think about revolution and

2) his failure to articulate an anti-capitalist agenda shouldn’t negate the consciousness-raising messages in his music, especially when so many artists and entertainers who have similar platforms abdicate that challenging task. Ultimately, he chose to take a stand. He chose to use his art as a weapon against injustice and ignorance. That is what is most important, what we must not forget when we set these impossibly lofty standards for our freedom fighters. By choosing to “carry the cross” Nas opened himself up to scrutiny either way. But in doing so, he also liberated his art, placing it above petty inspection. When we talk about Bob Marley we never engage in absurd conversations about the number of Top Ten singles he had or the number of records he sold in the first week. We talk about the message he was trying to convey, the love he had for his people, his willingness to stand in the path of destruction and say what we all know to be the truth. We must begin to look at songs like “I Can” the same way. The lyrics are meant to inspire and open the eyes of young people and old. It challenged the conventional wisdom that says there is no audience for intelligent, compassionate music, that rappers aren’t knowledgeable about their history and that the art form can’t play the dual role of edu-tainment. “I Can” was a love letter to a young black America cut from the same cloth that informed Malcolm’s belief that mental slavery was the chief ailment in black America. Better than any other rap song, “I Can” artfully illustrated the rise and fall of ancient African empires and the genesis of Western racism. The song managed to seamlessly balance entertainment with consciousness, which in itself is a notable achievement. “I Can” ultimately ended with following verse:

“If the truth is told, the youth can grow/They’ll learn to survive until they gain control/ Nobody says you have to be gangstas, hoes/Read more, learn more, change the globe.”

The audience to whom Nas was directing his powerful message was unequivocally and uncompromisingly black. The point is that, like Malcolm, Nas’s message pointed increasingly toward unity, self-love and self-defense. On the other hand, Jay-Z directed his message and music to a predominately mainstream audience’s negative image of the ghetto. He wasn’t interested in prickling his audience’s social conscience or challenging it to live up to the American creed. Quite the contrary, Jay-Z successfully exported a mainstream Dream that didn’t change social or economic relations for anyone except himself. If anything, what it did was show a clear distinction between him and Nas that could be summed up as- Jay was in it for the cash, Nas was in it for the message.

Rebellious With A Cause

Nas released his eighth album, Street’s Disciple, in the midst of the national scandal surrounding the Iraq War and a presidential campaign season that was splitting the country apart. Between the Abu Graib revelations first exposed in Seymour Hirsch’s New Yorker exposé and the utter embarrassment of the Bush Administration’s mishandling of the war the American public had been duped into supporting, the nation’s spirit was disturbingly glum. The 2000 election had left many Americans with shaken faith in Democracy and in their leadership, but the stories of young American men and women being blown apart by car bombs on a weekly basis were making it too much to bear in silence. Internationally, America’s reputation and support sank to all-time lows and the fears that had choked out dissent in 2001 and 2002 had turned into outright rage by 2004. Street’s Disciple was a sprawling, ambitious, uncompromising double album. Of all of Nas’s albums to date, it was the least commercially accessible and easily the most aggressively political. From the outset, it dove headlong into social commentary, political criticism and race consciousness. Though the album debuted at #5 on the Billboard Hip-Hop/R&B chart and went on to sell more than one million copies, it failed to garner the critical or commercial attention the previous two albums had enjoyed. But that shouldn’t be mistaken for the album missing its mark, or failing to fulfill its mission. Certainly by 2004 artists like 50 Cent, Kanye West, T.I. and Wayne were making their names, but the mere fact that Street’s Disciple was able to move more than a million units without the traditional commercial hit said something about Nas’s status within the culture. No other artist could’ve released a more politically charged, anti-mainstream, neo-Black Power album and garnered comparable fan support in part because no other relevant artist had the credibility, audacity or creative energy to make such an album. Only an artist comfortable with himself, confident in his beliefs and clear about his artistic vision would’ve dared risk alienating white listeners and black listeners alike by brazenly announcing, “This ain’t 50/This ain’t Jigga/ This ain’t Diddy/This ain’t pretty” at a time when most rappers would have killed for the success those three—50 Cent, Jay-Z and Sean Combs—were enjoying. On “American Way,” an obvious (and odious) nod to the Russell Simmons-backed Hip Hop Summit Action Network’s Hip Hop Team Vote campaign, Nas articulated the double-bind millions of young voters of color are confronted with each election season and criticized the way hip-hop moguls and civil rights stalwarts help perpetuate the failed system. On the searing, P-funkesque synth-driven song reminiscent of Ice Cube circa Death Certificate Nas rapped, Rap guys get bank and think they messiahs/But they liars/Vote for who now, you red, white and blue, I’m American too/But I ain’t with the president’s crew/What you peddlin’, and who you peddlin’ to/Tryin’ to lead blind sheep to the slaughterhouse/Talkin’ ‘bout Rap to Vote, you ain’t thought about/The black vote means Nathan/Who you gonna elect, Satan or Satan? In many ways the 2004 election and the HSAN’s voter registration campaign brought to light what S. Craig Watkins referred to as the “clash between those who see hip hop as a source of profit and those who view it as a source of politics...” The HSAN, largely because of Russell Simmons’s charisma, connections and political ambitions, came to be seen by the mainstream political machinery as the legitimate voice of the Hip-Hop nation. Simmons substantiated his credibility via his track record and access to the movers and shakers of the hip-hop world. During the ‘04 election the HSAN focused the bulk of its efforts on registering young voters. Like Jesse in ‘84 and ‘88, the organization based much of its authority on its ability to excite people about voting, but also, like Jesse, the HSAN turned into more of a roving religious revival than an actual progressive political movement.

Despite its popular efforts and mainstream support, many in the Hip-Hop nation didn’t feel the HSAN was speaking for them as much as it was speaking to the corporate interests Simmons was aligned with and seeking to cash in on. In the end, Simmons drew the ire of many hip hoppers who wondered if he wasn’t trying to position himself as the next black messiah. As a result, grassroots activists who felt disconnected from the HSAN (which, oddly enough, was being officially run by civil rights holdover, Dr. Ben Chavis Muhammad) organized the National Hip Hop Political Convention. Of the event, which took place in the summer of 2004, Watkins wrote, “Unlike Simmons, the convention sought to gain its political prestige and influence from below, opting to be an organization comprised of the people rather than personalities.” Although the convention was far from perfect and probably raised more questions than it answered, the real and lasting effect of its efforts to organize and assert itself was the articulation of an opposing agenda. Unlike the HSAN, the Hip Hop Political Convention saw hip hop as a political voice outside of the system that needed to exert pressure on the system to make it more reflective of the people and the values that make up this nation. The opening set of songs on Street’s Disciple captured the spirit of dissent and distrust that the Hip Hop Political Convention was organized to give voice to. Where Russell Simmons and the HSAN were content with “peddlin’” an agenda that pushed the Hip-Hop generation closer to the mainstream, Nas offered a critique of the potentially flawed logic upon which that agenda was based. Malcolm had a similar mortal distrust of American politics and contempt for integrationist race leaders like King who insisted that America was capable of redemption. For Malcolm the line had to be drawn boldly and broadly. Black folks had to understand who the enemy was in order to organize and resist it. Malcolm was also clear about the enemy within, meaning the “so-called Negroes” who contributed to the continued oppression of other blacks, and didn’t hesitate to point them out. On “These Are Our Heroes” Nas engaged in the kind of internal criticism of black athletes—NBA star Kobe Bryant in particular—and entertainers that has gone on within black communities for years. Athletes and entertainers, according to Nas and others, have a special mission and responsibility to the race, particularly the younger generation. At times the rhetoric on the song sounded needlessly cruel and misguided, but, again, Malcolm used a similar tactic (he once called King the “Reverend Dr. Chickenwing”) to awaken people from their slumber. By comparing modern athletes and entertainers to “spooks,” “coons” and “jiggerboos” who white America touts as “respectable” and “decent” black heroes the youth should emulate, Nas continued the line of criticism Malcolm (and Marcus Garvey and Du Bois) popularized in the 1950s and ‘60s when he called integrationists “puppets and parrots” and “Negro stooges” who’d been “endorsed, sanctioned, subsidized, and supported by white Liberals.” What made “These Are Our Heroes” particularly potent was the fact that Nas didn’t simply target the usual cast of characters; he also made a sophisticated critique of rappers (“pickaninnies”):

“You talk black/But your album sounds like you’d give your nuts for a plaque/You don’t ride for the facts like, um, say Scarface, you don’t know what you feel/Y’all too safe.”

The implication was that not only had black athletes and actors “sold-out” for fear of falling out of favor with their corporate sponsors, so too had rappers. Hungry for mainstream acceptance, they compromised their art and steered clear of controversy. Rather than simply rehash Malcolm’s sentiments, Nas showed that he’d updated Malcolm’s analytical framework for the 21st century. For all of its social criticism and political commentary, Street’s Disciple’s polemical thrust wasn’t limited to the need for self-knowledge and unity. It didn’t simply settle for being contrary, coarse and cold. It was also an album drenched in love: love of self, love of country, love of the people, love of family and love of hip hop. In my opinion, in fact, the album’s exploration of love as a wide-ranging theme made it a uniquely complex manifesto for a time period in which the Hip-Hop generation was (and is) sorely in need of healthy models of love. So many of the problems in contemporary black America can be traced to a lack of love and too often the music has been content to reflect that lovelessness, self-hatred and contempt for the community. Tupac is much admired by people worldwide because he had great love for people, a love that sparkled in his eyes and screamed from his lungs. “Keep Your Head Up,” “Dear Mama” and “I Ain’t Mad at ‘Cha” will probably forever stand unparalleled in their authentic, poetic evocation of black love. Nas, to his credit, has his own catalog, including the epistolatory classic “One Love” and “Black Girl Lost.” The particular strain of love emanating from Street’s Disciple, however, was unique. The duet with his father, jazz legend Olu Dara, was a first of its kind. It not only brought together jazz, blues and hip hop, but a black father and son. Beyond the quality of the song, the message conveyed to a community in which 70% of black youth are born into single-parent homes, where the absence or estrangement of the father is so common that his presence is an anomaly, was revolutionary. So too were the series of songs about his love for his wife and the anticipation he felt about marriage. Again, within hip-hop culture the notion of a man willingly giving up the “playa” lifestyle for marriage was and still is unheard of. Of course, rappers get married and raise families, but the industry thrives off of the notion that real men don’t settle down, don’t get married and certainly don’t look forward to it.

Younger black men and women certainly have good reason to doubt the institution of marriage, but the open, unapologetic acceptance of unwed coupling and parenting that exists among the Hip-Hop generation has made it seem as though there are no redeeming qualities in marriage. By celebrating his own marriage on songs like “Getting Married” and “No One Else in the Room,” Nas cut against the prevailing sentiment and declared his love and his intention to legitimize that love through a union under his God’s law. With “The Unauthorized Biography of Rakim,” Nas made yet another culturally significant contribution to consciousness-raising. Rap, unfortunately, has been regarded as disposable art for as long as it has been a part of pop culture. Although in recent years scholars and writers and curators have been working to preserve and legitimate the culture, Nas’s novel notion of recording the biography of Rakim—the rapper to whom he owes a great deal and with whom he is often compared—showed his own growing concern with preserving the culture and with shining the light on those who paved the way. By recording a song that told the story of one of the most innovative and important artists to ever pick up a microphone, Nas participated in the preservation and legitimization of a culture in need of both. Finally, Nas opened up yet another side of himself—and in so doing another dimension and direction for rap music—with the album’s final track, “Me and You,” dedicated to his daughter. In it he confessed his shortcomings as a father, offered his daughter advice and expressed gratitude for her love. Rap audiences are familiar with dedications to mom (both Nas and Jay-Z have contributed to this catalog) but, again, because hip hop has allowed itself to get stuck in a juvenile box, rap artists have typically shied from exposing their feelings toward their children. (My guess is that they fear alienating younger fans.) In any event, the song transcended the personal relationship Nas had with his daughter as a way of making a larger cultural contribution. Children need to know they are valued and appreciated by their fathers. They also need to be given guidance and support. Taken separately or together, each of these songs challenged the conventional wisdom when it comes to rap artists, resisted the limitations we impose on ourselves about the acceptable subject matters for rap songs and, perhaps most importantly, provided revolutionary models of black love that a struggling generation can be guided and inspired by.

About the Creator

Brian

I am a writer. I love fiction but also I'm a watcher of the world. I like to put things in perspective not only for myself but for other people. It's the best outlet to express myself. I am a advocate for Hip Hop & Free Speech! #Philly

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.