What is space law?

Second extract from a dissertation on property rights in space: history, law, and jurisdiction

Space law is a body of legal principle, an area of law, defined by its subject matter and the human activities it covers, rather than a specific jurisdiction or location. Space law is among a growing number of emerging categories of law, along with others such as media law or environment law, which ‘retain the idea of keeping study and teaching within categories defined by a body of legal principle which corresponds with common law or statute’ (Bartie, 2010, p350). The body of legal principle that forms the core of space law is found in international law, as might be expected, given the acceptance during the latter half of the twentieth century, of international legal regimes underpinning the law of other areas beyond national jurisdiction: the sea, air space and Antarctica.

This article has been taken from Chapter 4 of the author's 2018 master's dissertation, Law and property rights in outer space: celestial bodies and natural resources. The dissertation was completed in October 2018 and submitted to The Open University as the final part of a Master of Laws degree. The legal research is now considerably out of date and should be read in that context. It is reproduced here as the background, history, and bibliography are still relevant. Read Part One of Law and Property Rights in Space

The law of outer space is part of ordinary public international law and shares in its sources. It is ‘a new area for the application of law, it has burgeoned since the launch of Sputnik I in 1957’ (Lyall & Larsen, 2018, p35). Space law is one of 'a widening number of areas on land, sea and finally air as well as new subjects, such as humanitarian ones, which are covered by an ever larger body of law and treaties' (Jankowitsch, 2015, p1).

Perhaps a simpler way to think of space law is that it is the body of international law and national laws that deals with outer space matters. Space law includes, not just international treaties and national legislation specific to space activities, but it can also be considered to include domestic legislation on other areas of law that might touch on space activities. The regulation of television broadcast services under the UK Telecommunications Act, 2003, for instance, includes provisions for direct satellite television broadcast services intended for reception in UK homes.

History of the development of space law

Interest in the need for a law of outer space was evident in the early part of the twentieth century at a time when civil aviation had begun to be regulated at the end of the Great War. Many of the concepts that were brought together in the Paris Convention (Convention Relating to the Regulation of Aerial Navigation, 1919) derive from Roman Law and the maxim (developed after the Roman era) Cujus est solum, ejus est usque ad coelum. The rights of private landowners to the space above their property ‘up to the heavens’ were recognised by Grotius, writing in 1625 (Cooper, 1952).

During the interwar years, there was considerable interest from scientists and engineers, particularly in Germany, in developing a practical rocket engine. From these developments, stemmed various theoretical works on the possibilities for launching rocket-powered craft beyond the atmosphere into Earth orbit and beyond (Piszkiewicz, 1995). This raised the question of whether a separate legal regime would be needed for outer space, that realm beyond ‘the complete and exclusive sovereignty over the air space above.. national territory’ (Paris Convention, Article I).

In 1932, Vladimir Mandl, A Czechoslovakian lawyer and university professor (who also designed a multi-stage rocket for space travel) published a German-language monologue on the theory of space law. The work considered the similarities and differences between hypothetical (outer) space law and aviation law (Mandl, 1932). Any further such work by Mandl was prevented by the German invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939, after which German rocketry was subsumed into the Nazi war effort. Following Allied victory in 1945, the US and Soviet governments separately acquired rocket experts from Germany and the expertise that helped them to develop their respective space programmes (Piszkiewicz, 1995).

Interest in the development of a separate law for outer space was rekindled in the 1950s as a direct consequence of the programme planned by the international scientific community for the International Geophysical Year (IGY) that took place from July 1957 to December 1958. Special attention for the planned international scientific study was given to each of the two polar regions, the equatorial region and three pole-to-pole meridians. Scientific study of the Antarctic and the exploration of outer space both ranked as major objectives of the IGY (Jessup & Taubenfeld, 1959, p112). The IGY also provided the opportunity for the launching of the first artificial satellites into Earth orbit, firstly by the Soviet Union and then by the USA (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine).

Writing in 1956, the year before the IGY and after the USA and Soviet Union had each announced its intention to launch a satellite into space, Cheng outlined the need for international regulation of space flight (Cheng, 1997, p3). It is clear from this and other contemporary works that there was considerable academic interest at the time, in the development of the international law of outer space. Considerable momentum for international regulation also came from the national governments of the USA and Soviet Union, both concerned about the escalation of the arms race into outer space.

During the IGY, research projects in Antarctica saw unprecedented international cooperation by the participating parties. This is despite competing claims of sovereignty over parts of Antarctica from Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom, which were suspended for the duration of the project (Raclin, 1986, p731). The goodwill thus generated culminated in the signing of the Antarctic Treaty on 1 December 1959, which effectively suspended all claims of national sovereignty in the region. The successful entry of the first artificial objects into space during IGY also led to the UN General Assembly adopting the resolution establishing the ad hoc Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) to study and report on the legal problems that might arise from space activities. The resolution noted the success of the IGY and plans to continue scientific cooperation and recognised ‘the great importance of international cooperation in the study and utilization of outer space for peaceful purposes.’ (UNGA Res. 1348, 1958). It can thus be seen how regulation of exploration and scientific study of Antarctica and outer space share a common origin in the international cooperation brought about by the IGY. Regulation of an inhospitable environment such as Antarctica may also be seen as providing a close analogy with outer space.

Further international discussions of the need for peaceful uses of outer space in the years that followed led to the adoption, in 1963, of the Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space (UNGA 1962 (XVIII)).

Peaceful uses of outer space were, at the time, considered to involve only states and not non-state actors. This was because only states, and initially only the two cold war rivals, had the capability to launch objects into outer space (Lyall & Larsen, p37). As US space capability developed, non-state actors were involved to the extent of providing contracted services to the US space agency NASA. Even when commercial communications satellite operators came into being in the 1960s, they relied upon the national space agencies for launch capability. It wasn’t until the 1980s that commercial space launch services became available.

In addition to launch services and satellite communications, non-state space activity currently includes satellite navigation, direct TV broadcast from satellite and remote sensing. There are also commercial missions planned to extract minerals and volatiles from asteroids and others to take wealthy passengers (dubbed ‘space tourists’) on experience excursions into sub-orbital space. There are even non-state projects aimed at establishing human settlements in space, such as the privately funded Mars One mission, which currently plans to land the first human, permanent settlers on Mars in 2032 (Mars One Roadmap).

Author note: Mars One declared bankruptcy in 2019

The Apollo Moon programme made extensive use of private contractors, during the 1960s and 70s, to provide equipment and expertise. This need for commercial support (and attendant private funding) for the American space programme was further considered for the 1986 report of the US National Commission on Space. The report identified the need to provide materials such as water ice for oxygen and propellant, as well as regolith (surface solids) materials for shielding spacecraft from harmful solar radiation. It made it clear that private enterprise could be expected to provide investment funding for such activities if there was sufficient prospect of rapid returns. In the USA at least, it had been accepted that space exploration required an element of commercial as well as state sponsorship (Pioneering the space frontier, the report of the National Commission on Space, 1986). This indicates that, during the 1980s as previously, commercial activity in space was closely tied to state activities in space.

It has long been considered by many in the scientific community that ISRU is an essential requirement for the future exploration of deep space, particularly any human missions to the Moon, asteroids or Mars. (NASA online ISRU pages). One of the main reasons for this is the high cost of raising any materials into Earth Orbit and beyond. Rocket propellant requires many times its own weight of propellant to be launched into space. Rocket propellants can be produced from water ice extracted from the Moon and asteroids. Water ice can also be processed into drinking water and oxygen for astronauts, while it is anticipated that other materials, such as metals, may be capable of being used for manufacturing items in space, perhaps even spacecraft modules.

Until 2015 and the CSLCA, the question of whether any natural resource found on the Moon or asteroids could be extracted lawfully had not been directly addressed in any form of legislation, or in any international convention. There was also no case law, since there has yet to be a claim of title from anyone with an immediate prospect of possession. One of the few relevant cases, Nemitz vs. USA and others, is considered in Chapter 5.

The related question of whether outer space, including celestial bodies, can be appropriated has, however, been addressed. UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolution 1721 (XVI), 1961) included two fundamental principles, in this respect. Firstly, that ‘international law, including the charter of the United Nations, applies to outer space and celestial bodies.’ Secondly, that ‘outer space and celestial bodies are free for exploration and use by all States in conformity with international law and are not subject to national appropriation.’ The resolution also reiterated the peaceful use principle.

The principles of peaceful use and non-appropriation were further embedded in international law with the conclusion of the Outer Space Treaty (1967) which ‘translates into treaty obligations the basic ideas expressed in those earlier UN Space Resolutions, and particularly in the ‘Principles’ Declaration of 1963.’ (Lyall & Larsen, 2018, p50). Article II established that outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

The iteration of the principle of non-appropriation in the 1950s should be seen in its historical context. ‘The middle of the twentieth century was a tumultuous time for international affairs coinciding with the Cold War, the development of the United Nations system, and decolonisation resulting in the emergence of many new states which sought to challenge the existing order, including the ‘Eurocentric’ focus of international law’ (Rothwell & Stephens, 2016).

It was in this climate of cold war suspicions and decolonisation, tempered by the international cooperation of the IGY and of international activities in Antarctica, that efforts to agree a legal basis for space activities developed.

Sources of space law

The early development of the international law of outer space took place amid the general understanding reached between the USA and the Soviet Union, that nuclear weapons would not be tested or deployed in outer space. As has been shown, the technology for space exploration emerged partly from the Nazi rocket weapons programme in the closing stages of the Second World War. From the conclusion of that war and the effect of the Cold War arms race, the threat of a global nuclear war emerged. The USA was uncertain how to react to the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957 and both cold war belligerents were keen to avoid further escalation of the arms race into space. Whether for political reasons, economic necessity, or simply because of the uncertainty about how far the technology could take them is difficult to establish (Jankowitsch, 2015, p3).

In 1963, the Partial Test Ban Treaty prohibited nuclear weapons tests or any other nuclear explosion in the atmosphere, in outer space, and under water. Although primarily aimed at protecting the global environment, the treaty provided the first limitation on warlike acts in space (Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, 1963). Given the geopolitical climate of the 1950s and 60s and the emergence of a ‘space race’ between the two cold war belligerents, there could be no doubt about the need for a general treaty to regulate activities in outer space. The space race may in some respects be seen as an arms race by other means but, as such, it should also be seen as a peaceful alternative to the nuclear escalation that had been taking place. It could be argued that, in this general atmosphere of cold war competition, in the closely connected development of nuclear missiles and space rockets, the international law of outer space emerged.

The space race may be seen as an arms race by other means but also provided a peaceful alternative to nuclear escalation

Space law is therefore a body of law that derives first and foremost from international law. It can be said to have begun with the desire of the international community, through the UN, to ensure that the exploration of space would be peaceful and not territorial. The intention was to avoid the kind of aggressive territorial claims that marked the two world wars of the first half of the twentieth century. If humanity was to avoid such devastation in the latter half of the twentieth century, then the exploration of the newly opened domain of outer space, as with the Antarctic, must be peaceful, cooperative and without national territorial claims. The first and most important source of the law of outer space is therefore the body of international law that developed through the United Nations in the 1950s and 60s.

For over fifty years, the general principles of the law of outer space have been enshrined in the Outer Space Treaty. The Treaty may be considered foundational, including principles of space law ‘of a generality that have passed into customary law ’ (Lyall &Larsen, p37).’ The treaty was drawn up in haste, however, owing to the need to find a legal basis for the overflight of sovereign territory by satellites, following the launch of Sputnik 1. As a consequence, the meaning of some parts of the treaty is not clear, as will be discussed further below.

Article II is of particular important to any consideration of property rights.

The main principles outlined in the Outer Space Treaty are further elaborated in the subsequent UN treaties on outer space. These are the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space (Rescue Agreement), 1967, the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (Liability Convention), 1972, the Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space (Registration Convention), 1976, and the Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (Moon Agreement), 1979.

Of these four, the treaty that is most relevant to the issue of property rights in addition to the Outer Space Treaty, is the Moon Agreement. It includes such statements as ‘The moon and its natural resources are the common heritage of mankind’ (Article 11).

The problem is that no major space power has ratified the Moon Agreement. France signed in 1980 and India in 1982 but neither has ratified the Agreement. It remains an agreement between its state parties but has little, if any, influence on the reality of international space law for any states and private entities in the process of planning space missions (Ch: 2.1). More importantly, neither the Moon Agreement nor the Outer Space Treaty anticipated the level of commercial space activity prevalent now, particularly in respect of ‘space mining’. This leaves the question of property rights in space open to interpretation.

Author note: France and India have both since signed up to the 2020 Artemis Accords, a set of non-binding principles for peaceful space exploration which includes principles on responsible space resource utilization.

In addition to the five UN treaties, there are other treaties contributing to the international law of outer space, such as the Constitution and Convention of the International Telecommunication Union (1992). The ITU and its predecessor organisations have been regulating international telecommunications since the first International Telegraph Convention was signed in 1865 (International Telecommunication Union, ITU). This is a good example of an existing regulatory framework extending its reach from electrical cables laid across land, first into the ether with the coming of wireless telegraphy at the end of the nineteenth century, and then into space during the twentieth century. Unlike aircraft, radio waves are not restricted to the atmosphere and can of course travel through outer space.

Interestingly, the ITU had considered the need for regulation of activities in outer space before the United Nations did. In 1959, when only the USA and USSR had achieved successful launch of an object into space, the ITU resolved to control radio frequencies from space craft ‘if necessary.’ ‘Thus, the oldest spacialized agency of the United Nations takes the lead in being the first to have introduced a set of rules of international treaty law relating to activities in space.’ (Cheng, 1998, p99).

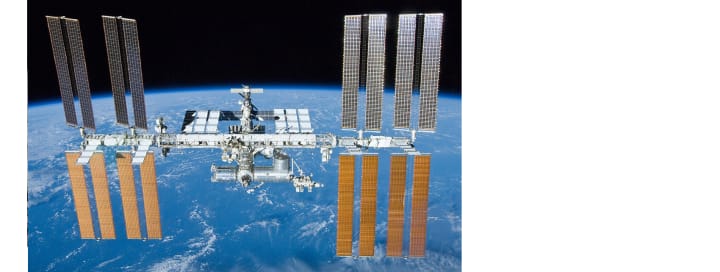

There are also some very specific treaties covering space matters. One example is the Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany concerning the Landing and Recovery of a Space Capsule in Australia (1995). Although the agreement included that any activities carried out within Australian jurisdiction were subject to Australian laws (Article 4), it made reference to the ‘peaceful purposes’ of the planned mission and stipulated that Australia was not a launching state within the meaning of Article 1 of the Liability Convention. Another specific treaty of interest to the question of property rights is the framework treaty establishing the agreement for the operation of the International Space Station (ISS Intergovernmental Agreement, IGA, 1998, referenced in Chapter One).

Consideration of customary international law, problematic at the best of times, is also relevant to the international law of outer space. This is particularly difficult is this context given the absence of any senior judicial decisions relating to space law (Lyall & Larsen, p38). As previously stated, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has yet to consider a matter of space law and there are no relevant cases scheduled at the time of writing (ICJ Pending cases). The number of cases listed relating to maritime territorial disputes might, however, be an indication of the recourse that states might have had to the Court, had the legal principle of non-appropriation not been established by the General Assembly in 1963 (UNGA: 1962 (XVIII)).

Although the ICJ has not considered a matter of space law, the court has noted, in an advisory opinion on the legality of the use of nuclear weapons, that ‘UN General Assembly resolutions, even if they are not binding, may sometimes have normative value. They can in certain circumstances, provide evidence important for establishing the existence of a rule or the emergence of an opinio juris.’ (International Court of Justice Reports, 1996, p226). On this basis, UNGA resolutions may be considered a source of outer space law to the extent of the qualification noted by the ICJ. Of particular importance are the resolutions pre-dating the Outer Space Treaty, which established a number of important principles such as ‘peaceful use’ and ‘non-appropriation’. These principles, having been reiterated in UNGA resolutions, UN committee meetings, the UN space treaties and other treaties, and in countless fora since, should be considered to stand as principles of the customary international law of outer space, as Lyall & Larsen and others have observed.

Any study of international law should, however, be wary of overly confident assertions of principles that are believed to amount to an accepted international principle of customary law.

Of particular relevance to the question of property rights in outer space are national laws. Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty established the principle that the state responsible for an object launched into outer space retains jurisdiction and control over that object. This principle was further elaborated in the Registration Convention (1976). National legislation, including recent Acts such as the UK’s Space Industry Act, 2018 or Finland’s Act on Space Activities, 2018 also reference such principles. In most cases, national space legislation has no bearing on property rights beyond existing international law but, as in these two cases, is mostly concerned with the regulation of liability and registration, as required by the various UN treaty obligations. The Space Industry Act is also focussed on establishing and regulating space launch services and space ports within the UK.

At the time of writing (summer 2018), 22 states have notified the UN of national space laws (UNOOSA Space Collection) which seems a small number considering the number of states currently involved in space activity. For instance, 74 states have registered space objects with the United Nations, not including multi-state agencies such as ESA, Arabsat and Inmarsat, as well as The European Union (UNOOSA Online Index of Objects Launched into Outer Space).

As previously noted, there are few examples of relevant case law. Nemitz is discussed in Chapter 5, more in relation to the judge’s comments than for any impact the outcome might have had (Nemitz vs. The United States of America). It is difficult to explain the lack of case law. One explanation might be the degree of supervision of non-state space activity required by states (Outer Space Treaty, Registration Convention) acting to head off any legal challenge that might otherwise have arisen. Another reason might be the detailed planning required for space missions owing to the high level of risk involved in space exploration. This author can only speculate as none of the sources accessed during this study have addressed this question.

Finally, space law can include private agreements between state or non-state parties, which are made in order to allow different parties to work together within a legal framework, in the same way as any other business or other private contracts. In such cases, it would not be unusual to specify the jurisdiction applicable to the agreement and to the resolution of any disputes.

Boundaries and jurisdiction

This work has referred to the ‘domain’ of outer space and to space activities. While outer space is defined in the Outer Space Treaty as including the Moon and celestial bodies, the boundary of ‘outer space’ is not defined in any of the space treaties. It is important to note, however, that outer space activities do not take place solely in outer space. A rocket is identified as a space object for legal purposes when it is registered as such, under the Registration Convention. It can be a space object while it is being constructed, while it is being prepared for launch and remains a space object while it traverses airspace on its outward journey into orbit or further into outer space. It remains a space object even if the launch is unsuccessful and it never leaves the launch pad. If an object is launched into space and then returned to Earth, it is still a space object on return. This illustrates that space law is not limited to the domain of outer space but is applicable to a wide range of activities in outer space, in air space and on the ground.

This work has also referred to the ‘outer space domain’ because outer space does not constitute a specific jurisdiction. Outer space exists outside of national jurisdictions and will continue to exist outside of national jurisdiction in the absence of any valid national claim of sovereignty. There can be no valid claim of sovereignty as long as the non-appropriation principle recognised by international law applies. International law, including the Charter of the United Nations, applies to outer space and celestial bodies (UNGA Res 1721 (XVI), 196, ref Ch 4.1).

Outer space is a term that is not defined in the Outer Space treaty as such, but it is clear from the wording that outer space includes celestial bodies and the space separating them from each other and from the Earth. By definition, and through the development of the concept of air space and the needs of civil aviation during the twentieth century, outer space can be seen to be the domain beyond airspace. The ‘legal domain’ of airspace was defined in the Paris Convention (1919) and subsequently the Chicago Convention (1944). If every state has ‘complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory’ (Convention on International Civil Aviation, 1944, Article 1) then it follows that national sovereignty ends where sovereign airspace ends and outer space begins (Cheng, p8).

Defining the actual limit of airspace above national territory in the Paris or Chicago conventions was hardly necessary, given the practical limitation on any aircraft, which can only fly within sufficient density of atmosphere to allow the aero engines to function. It might be tempting to consider the atmosphere to be the delimiter of airspace, however any closer look at the science of the atmosphere indicates that there can be no clear boundary between Earth atmosphere and the ‘vacuum’ of space. This is due to the progressive reduction in density with the increase in height above the Earth (Wallace & Hobbs, 2006). No attempt to negotiate an internationally agreed definition within the UN has so far succeeded, and there has yet to be any agreement even on the need for such a delineation (UNCOPUOS Legal Subcommittee, Report of the April 2018 session, A/AC.105/1177/Annex II/11).

From the point of view of this study, the precise boundary between airspace and outer space is not particularly relevant, given that the nearest celestial body to Earth (other than landing or briefly transient meteoroids) is the Moon which, by any definition, is located in outer space. Space is also defined as including the Moon and celestial bodies in the Outer Space Treaty, Article II. For most other purposes, the generally accepted, but still approximate, lower boundary of outer space is the so-called Kármán line, at about 100 km above sea level (Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, see also Cheng, 1997, p227).

It goes without saying that there is no known upper (outer) limit to outer space.

It also follows that international law, including those laws relating to outer space, apply throughout the universe. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for instance, is indeed universal in its application. It applies and must be applied to every human person, every nation and every place beyond any nation, including the high seas, on Antarctica, and throughout the rest of the universe (final paragraph added by Author, December 2025).

Continue reading: Space law and property. Can anyone own an asteroid or any valuable minerals that bay be held within it?

Further information: Sources, references and further reading

Back to: Part One of Law and Property Rights in Space

About the Creator

Raymond G. Taylor

Author living in Kent, England. Writer of short stories and poems in a wide range of genres, forms and styles. A non-fiction writer for 40+ years. Subjects include art, history, science, business, law, and the human condition.

Comments (2)

This is fascinating, Ray. I sometimes write about space tech (not here) and this last question about owning an asteroid or mining and owning minerals found is truly relevant today. One of the latest NASA-ESA missions is on its way to Jupiter's moon Europa will be looking for underwater life and for minerals. What I see it could happen (due to human greed) is that the likes of Bezos and the others not far into the future will claim ownership of whatever it comes from space or is found in space as a source of something valuable or desired on Earth. Perhaps, space law and property should be specific for space rather than try to apply or copy the old Earthing laws.

Wow. This is insightful. We seldom think about it, but with constant space exploration (and I expect much more to come), outer space needs regulation. Something to think about this morning for me!